This is the last of Four Conversations in Lieu of a Retrospective an overdue exploration of the 20th century work of Paul Astbury (it is ongoing), the most important early British Postmodernist sculptor working with ceramics outside the vessel tradition. Scholarship in the field has failed to record and celebrate his legacy so Cfile has stepped in to give it a nudge. Images are drawn from archives of differing quality. Please excuse the unevenness. Quotes in italics are drawn from over four months of email correspondence between Garth Clark and Paul Astbury. You can click here for parts 1, 2 and 3.

In the past decade the most popular ‘new’ medium internationally for sculptors has been the ancient tradition of working with unfired clay as the finished product. Its Italian title is terracruda (raw earth) vs. terracotta (cooked earth). The list of artists from the top contemporary canon artists who work in unfired clay is impressive; Adrian Villar Rojas, Miquel Barcello, Erwin Wurm, Urs Fischer, Cassils, Anna Maria Maiolino. Clay serves different muses. Some works are simply allowed to submit to process, to crumble and erode as soon as they begin to dry, becoming what terracruda maestro, Rojas, calls “instant ruin”. Others use clay in a performance art context. Some works are given a long life due to material transfer, the miraculous fidelity of current bronze casting technology, with patinas that mimic dried or damp clay to eye-deceiving perfection. Marc Wanders is a case in point.

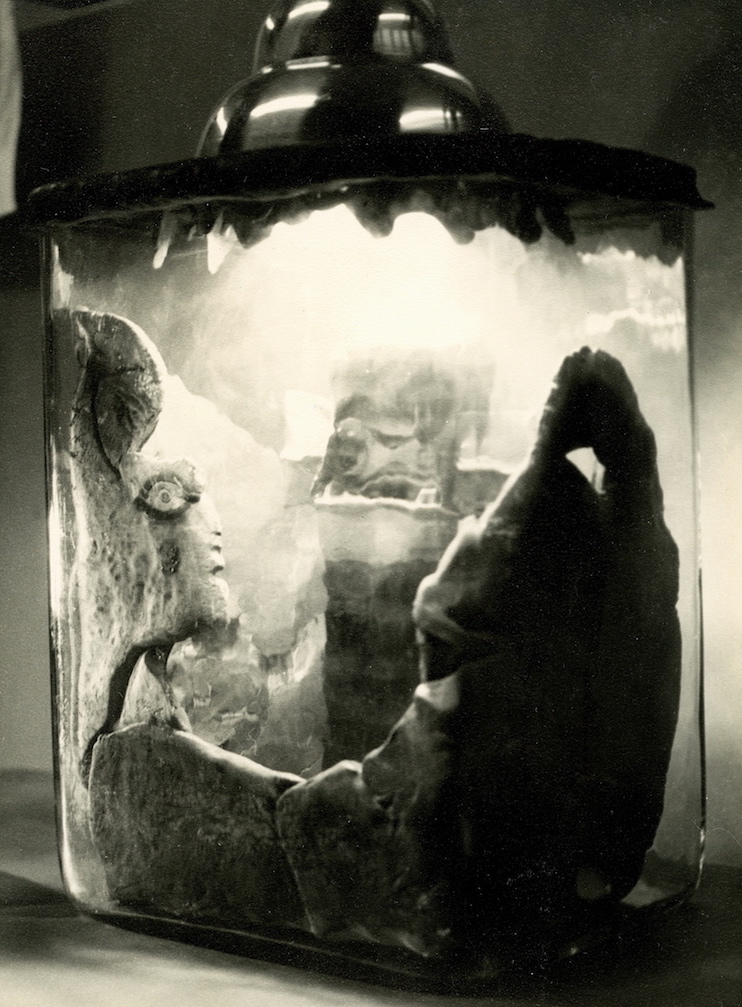

This leads back to Paul Astbury’s last major body of work in the 20th century. By 1993, again ahead of the curve, he was working with unfired clay. It was not the first time. His use of unfired clay dates back to the Stoke-on-Trent student years as we see with his 1967 work, Container of Another World, made from unfired clay, glass and smoke.

In 1994 this interest earned him a place on the prescient international touring show, The Raw and the Cooked, one of the decades most important exhibitions, curated by Martina Margetts and Alison Britton.

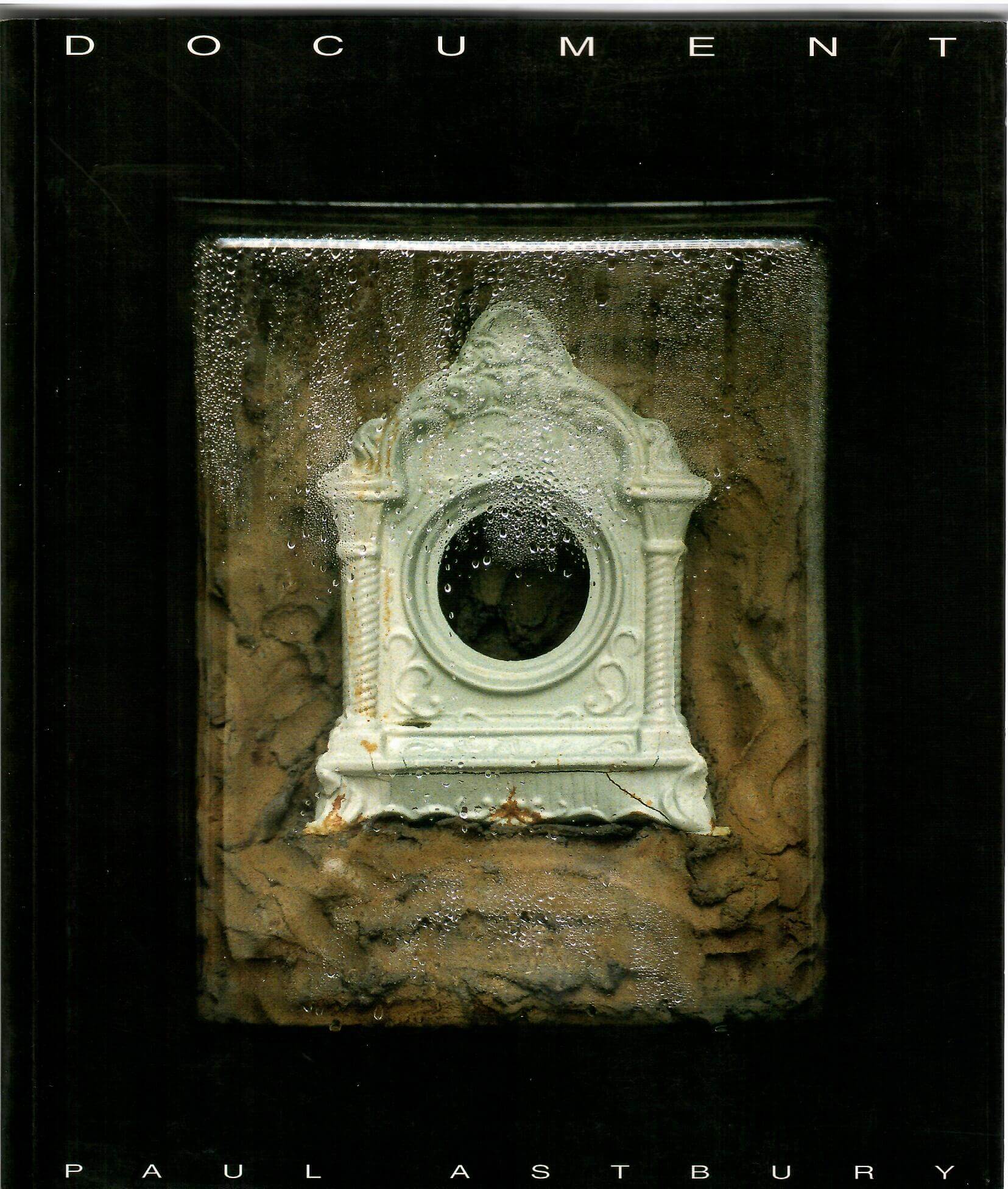

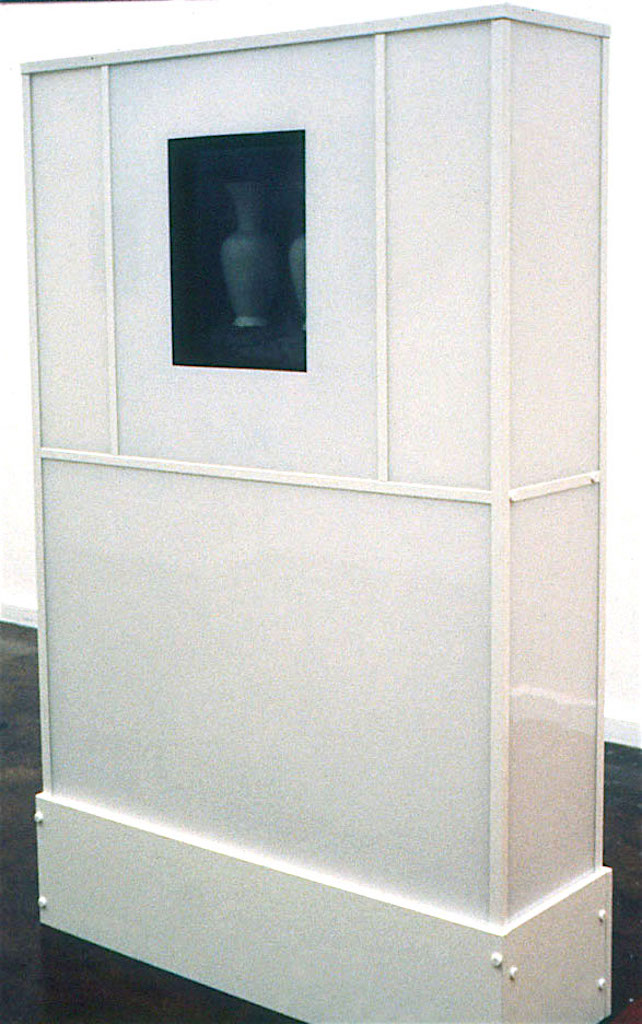

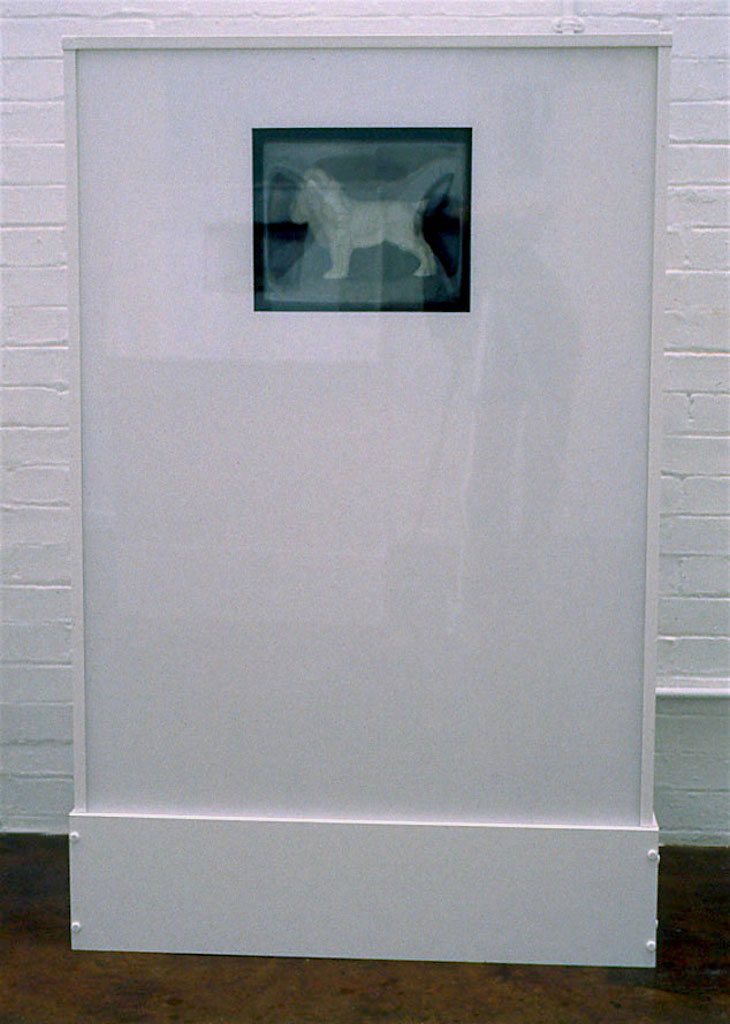

This aspect of his work was show twice by Diorama Gallery, first as Background in 1995, in handsome cold-white vitrines, in an installation that suggested an arcade of super-minimalist (and agonizingly slow) video games. Five years later, in 1999, the exhibition was reprised under a new title, Pulse. It was accompanied by a publication Document, that not only dealt with the unfired works but with Astbury’s legacy to date.

As the artist states apropos this exhibition:

Like anything that suggests a fetal or embryonic condition there is a supernatural remoteness, an imposed distancing from our own perceived sense of existence. This distancing is an important part of the work as is the interplay between moisture and atmospheric conditions.

The clay images themselves are far from that state where they could be practically handled or used in any real sense. The clay forms remain preserved and isolated, framed within their vitrines suggesting a further extension to the physical and psychological space separating the nature of the image from the viewer’s preconceptions.

I was involved with thoughts of process, particularly industrial pottery held at its halfway stage, fresh from the molds, unfinished and unfired, plus the raw clay sculptures of animals of 10,000 years ago, discovered in caves in the Pyrenees, an immature unfinished state of being.

This was my chance to work differently, the familiar, namely conventional domestic objects made by the pottery industry, teapots, cups and saucers, vases and much-loved ornaments of animals in an extreme unfamiliar way, the raw clay state.

In 2003 Astbury accepted an invitation from editor Emmanuel Cooper to write about his raw clay art in Ceramic Review. In his essay, “Other States” (Issue 200, March/April 2003) Astbury admits that, “wet clay makes me aware of a borrowed material, still uncommitted. In all these works, the material can be thrown back into the ground or reused in another piece.”

Laura Breen in her book, Ceramics and the Museum, 2019, writes that ‘Astbury began to explore the symbolic properties of wet clay and fired object in the early 1990s….Poised between raw clay and fired object, the works demonstrated that clay was just a medium, which might become something else as readily as a piece of ceramic.’

Laura Breen saw this work as evidence of Astbury’s fascination with the archaeological (or “future archeology’ as he saw it):

“[He] married the use of unfired clay as a symbol of the rise from the earth to the contradictory use of fired clay objects as something that can transcend death. Seemingly vulnerable in their unfired state, some of Astbury’s casts have defied the passage of time and endured for decades, whilst others have collapsed, bearing the marks of their existence. They thus serve as metaphors for the way in which even objects that are stored in cases and unused are reformed by the imperceptible contextual changes that surround them.’

Writer and critic John Houston noted that Astbury’s “artefacts are about artefacts’ and ‘If a single feeling dominates his work it is an imaginative fascination with the spirit that permeates technical advance. New needs, new faiths, new theories: some overtaken and fossilized by events, others merely faint images on a nebulous future.’

Emmanuel Cooper, editor of Ceramic Review, posited that Astbury’s sculptures, ‘offer a meditation on our understanding of creation, on the nature of its ever-changing cycle, and on the way civilizations develop and fall’.

Julia Davis, director of Diorama Gallery, saw the exhibition as a means to ‘by-pass the debate surrounding the boundaries between design and function, art and craft, use and context, replacing the hows for the whys; avoiding the concerns of method and control which have been overshadowed by the forces of time and nature.’

Document is the point at which the true analysis of Astbury’s oeuvre and contribution to postmodern ceramics should have begun in earnest but in fact is where it ended. No survey exhibitions. No retrospective. Hence the Four Conversations, hardly sufficient, but a start.

There were a few cameo appearances: his 2011 inclusion by Glenn Adamson in Postmodernism, Style and Subversion 1970 – 1990 at the Victoria and Albert Museum and in 2012, Shifting Paradigms in Contemporary Ceramics at the Museum of Fine Art-Houston where Prisoner’s Suite was one of the most admired works on this 250-object exhibition.

In closing, looking back on why Astbury has spent so much time on the margins we can actually pinpoint the moment when the split takes place between sculpture and the vessel in craft-based British ceramics. It comes in the mid-1970’s as Astbury notes:

Regrettably, the contemporary crafts scene and the category of ceramics did not understand the position I took and probably have never realized or acknowledged that I have always been a fine artist working with the medium of clay. Yet I was enlisted to bring up the craft medium to a higher plain of concept placing it nearer to fine art.

I think the crafts eventually took exception and tried to ignore the fact, little realizing that my approach would develop the field. Today, I think that attitude has lifted to some extent. In the early days (1973) I was approached by John Houston for the CAC (Crafts Advisory Committee, now Craft Council) who persuaded me to help develop ceramics.

It came about when a student of Astbury’s at the Horsey School of Art where he taught part-time told him how much she had admired his work on an exhibition The Craftsman’s Art at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

I went to the museum that following weekend and lo and behold two pieces of my work had been displayed without my permission. I saw red, could not believe their audacity and the following week rang the V&A to find out who was responsible for including my work in the show without my consent. I was given a name, John Houston who was part of the CAC.

Astbury was already upset with the CAC having walked past their Craft Shop in Covent Gardens and noticed that they were using his work as display stands for jewelry in their front window.

I asked for the work to be instantly removed from the V&A as I did not wish to be included in such a show. A day later I was contacted by John Houston. He apologized profusely, could we meet, it was very important, the pieces had been submitted by the Craft Centre and he had presumed I knew all about it.

We met at the V&A and viewed the pieces still on display. He was very apologetic and begged me to leave the pieces in the show, insisting that my work was really required to lift the standard. I explained my work was not craft but fine art, that because it was made of ceramic it should not automatically become craft. Craft did not have copyright over a material. He understood my concerns but still insisted my work was essential for helping the general public understand that ceramics was developing and needed artists like myself.

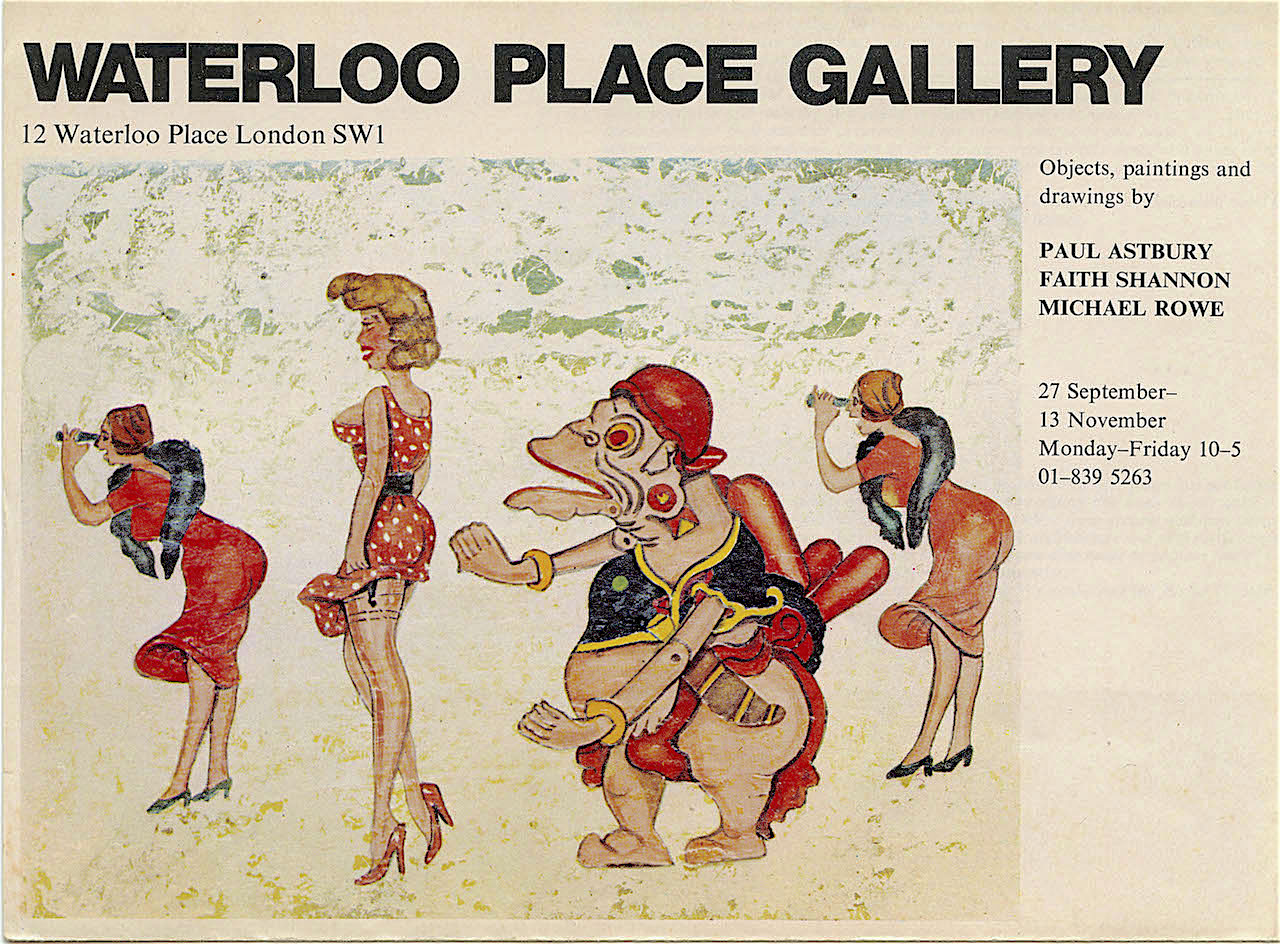

I was flattered by these comments, he seemed to have good reason and it was certainly refreshing to hear that ceramics particularly was being viewed in this way by an authority set to redevelop this art form and allow artists like myself forge the way ahead and I was invited into a three-man show for the opening of the Waterloo Place Gallery owned by the C.A.C.

Faith Shannon and Michael Rowe from 27 September to 13 November 1973.

The flyer features a drawing by Paul Astbury.

The show was well received and my ceramic work was shown together with my paintings. The other two participants were Michael Rowe, jeweler and Faith Shannon, book binder. One of my paintings was chosen as the poster for the Public Underground. I had no idea until I came face to face with my own work at Hammersmith tube station. It was a very weird experience. CAC was not strong on communication.

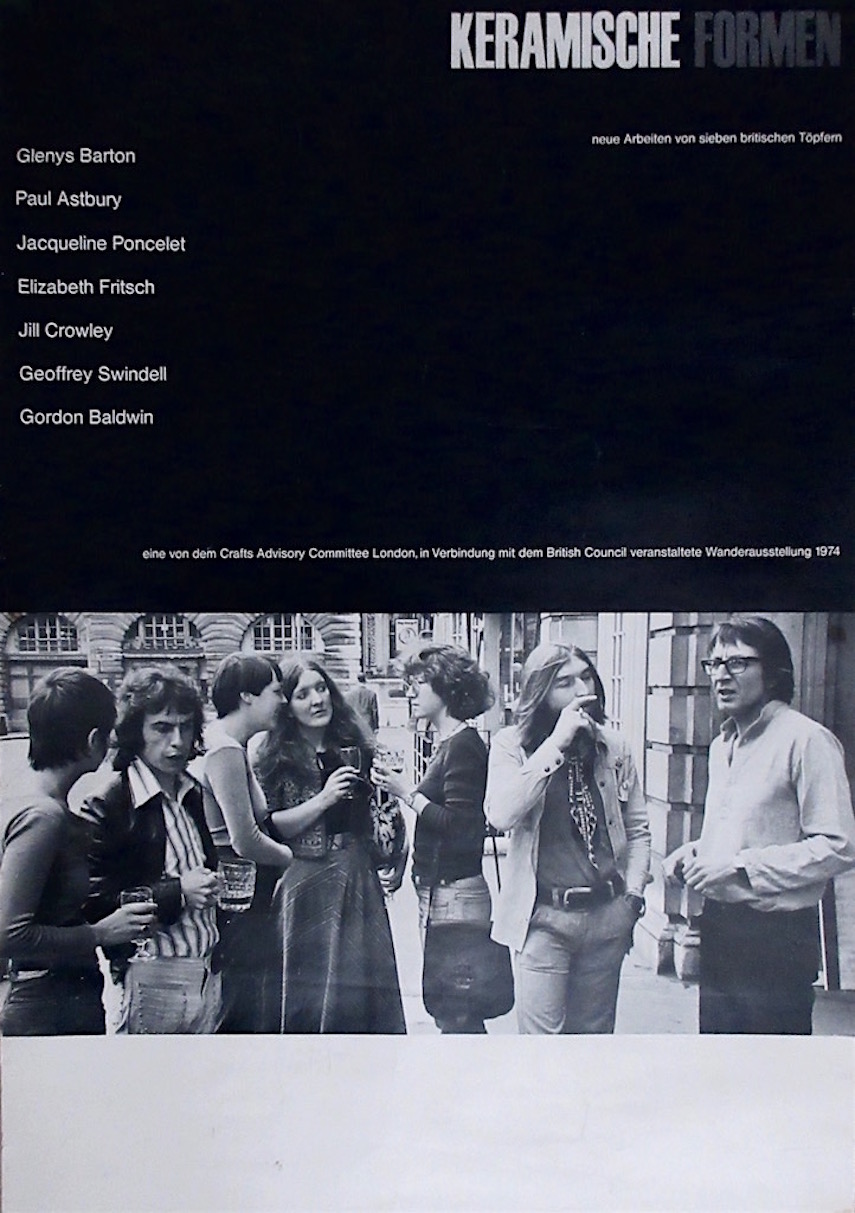

There was talk of a traveling show called Ceramic Form to Europe and John asked if I could recommend other ceramic artists who I felt ought to be recognized and included. At that time not even the C.A.C. knew who was who. I put forward the names you see on the poster, Glenys, myself, Elizabeth Fritch, Jacqueline Poncelet, Jill Crowley, Geoff Swindell and Gordon Baldwin. We were to become the new elite in ceramics.

But as time went on, Astbury’s role as the poster boy of an art-craft hybridization diminished, new people took over, “my fine art role became unwanted and the new Craft Council did not see my work meeting their criteria. Unfortunately, and embarrassingly for the C.A.C., they had already acquired a large amount of my work for the collection”.

In fact, the Council has the largest and most significant collection of his 1970’s art of any institution (the Museum of Fine Art-Houston comes next). You can visit the Council’s excellent group by clicking here and typing Paul Astbury in the search box.

The critic and voice for the crafts, Peter Dormer, accused the Craft Council of having too many fine art pieces in the collection and argued for such works to be removed. Those whose work was too art-like were excluded and found themselves adrift. The CAC never acquired another work by Astbury. As mentioned earlier, the sculpture galleries were not yet ready to take on art made of clay and the fissure between artists and crafters widened leaving the former without a champion.

So, it is time for catch-up, devoting scholarly resources to those artists in ceramics whose role as artists, perversely lead them to be sidelined by the field. And it leaves us with a question; when will Paul Astbury get his retrospective?

As an artist Astbury’s career summed up his own quest for art-truth in his art in “Other States” when he wrote that “…the past, the present and the future create the perceived reality, carrying the work through each moment and in this aspect confronting, rather than obeying, what is expected.’ And confront he did. Royally.

*now

Thanks Garth for mapping this really powerful work which I have known about since I was a student in the seventies and subsequently when I knew Paul in the late 80’s. It is so important to see his work captured in this way. I still now refer to his practice to students as being seminal in Ceramic Art. I look forward to the next chapter but where will it be documented know your excellent CFile is ending?