This, the second of Four Conversations in Lieu of a Retrospective turns a long overdue spotlight on Astbury’s career, hopefully the beginning of a deeper examination of his singular and powerful contribution to Postmodern ceramics in Britain between 1963 and 2000.

The quartet of essays cover some key works from the 20th century but are by no means a full retrospective. That requires a book length treatise. Further, these Conversations only deal with his sculpture, and his lively painting career is only touched on when it relates to the 3D.

The informality of illustration, more scrapbook than coffee table, is deliberate because of the wide range of image quality in the artist ‘s archives, more the edge of a research document. This has allowed more freedom in chasing the narrative. Paragraphs in italics are from email conversations between myself and Astbury over a period of four months. Click to access parts 1, 3 and 4.

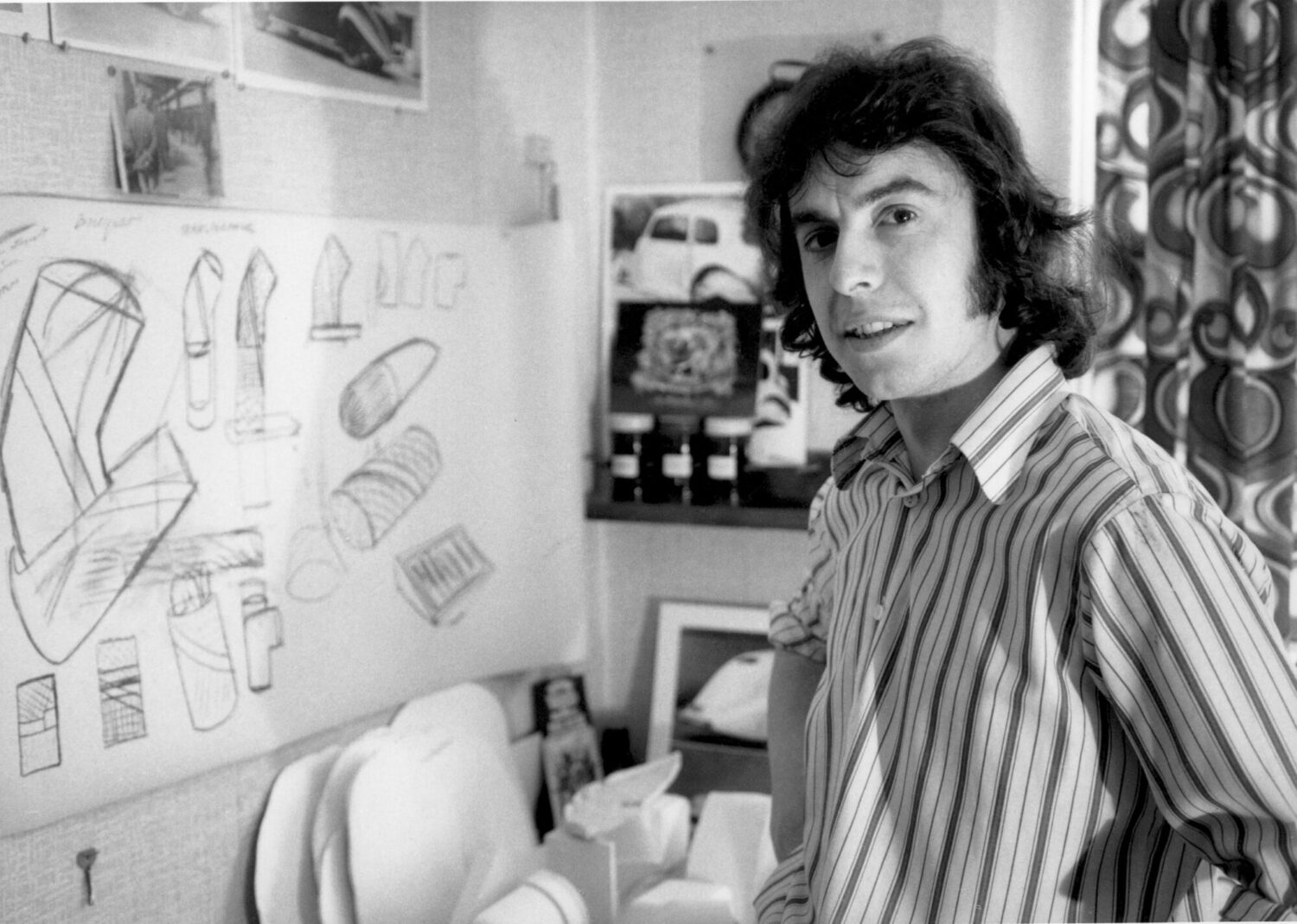

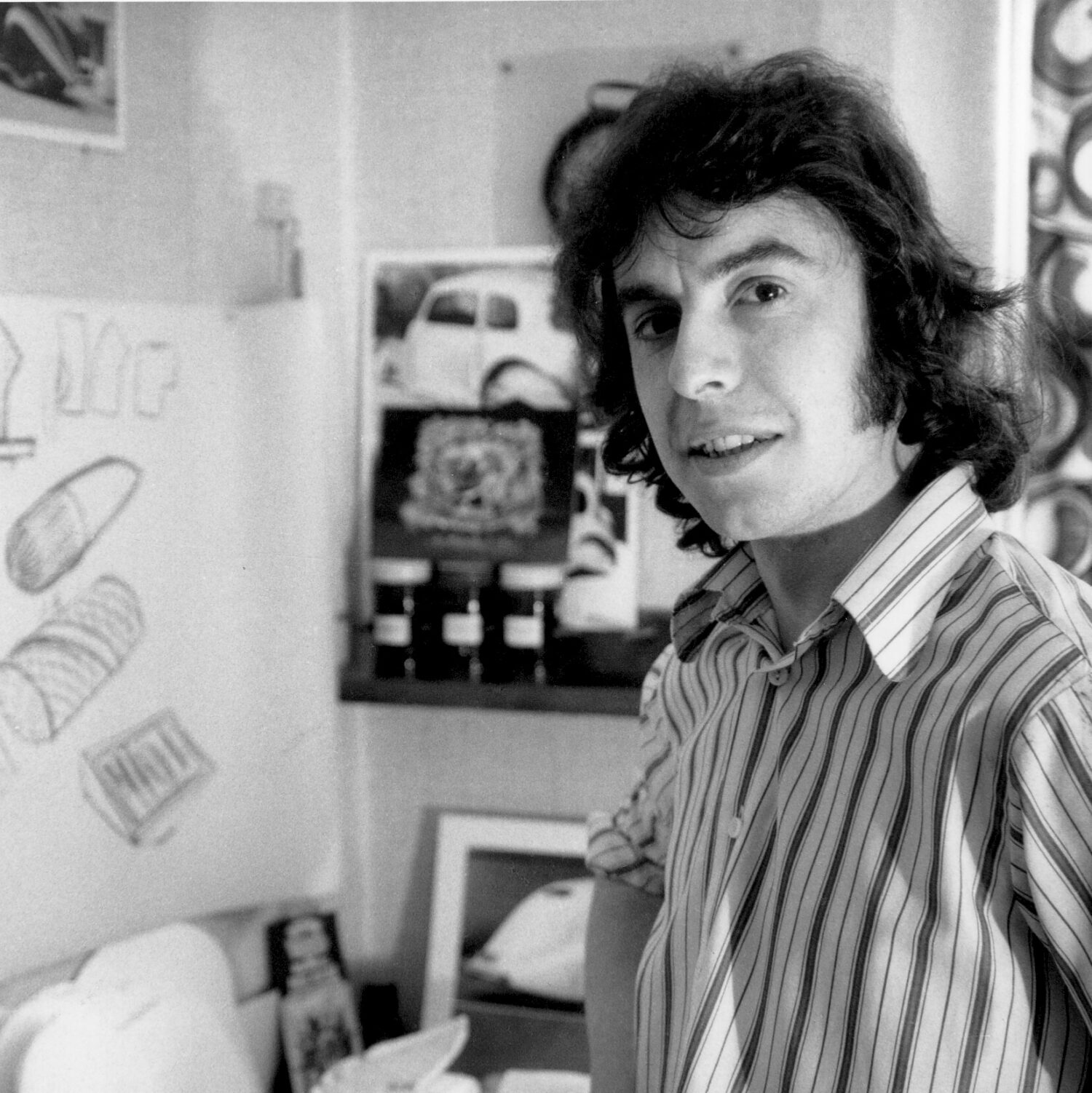

Even though Astbury was ambitious and had become a star student in Stoke-on-Trent, he never thought that he would be short-listed for acceptance into the Royal College of Art. When the call came, he was shocked. Little prepared him for the interview itself.

I sat at a table in an office with Queensberry, Dicky Chopping, Sam Herman, Eduardo Paolozzi, Hans Coper, Joe Shipley, and Peter O’Malley. There were objects arranged on the table and Q asked if I liked any. I pointed to three similar pots. Why those? I replied they reminded me of flying saucers.

Everyone was very amused. They were Hans Coper pots. Hans took it well. Q pointed to a heavy thick-walled ceramic object and again asked what I thought of it. I replied, not much, it looked clumsy. Q was tickled pink. He was having a field day. It turned out to be a pot by Hamada!

Two weeks later Astbury returned for a second interview. Queensberry was clearly keen on having Astbury admitted. But there was an issue. Dicky Chopping thought that Astbury wasn’t serious enough about the plant drawing classes. Plant drawing classes???

In those days the Department of Ceramics was still geared for industry. Indeed, it was called the Department of Industrial Ceramics. Plant drawing was intended to inspire pattern and decoration for industrially made ceramics. The drawing issue was resolved and Astbury was admitted.

Astbury arrived just as Queensberry was beginning to morph the department into an art-based facility that would revolutionize British contemporary ceramics, launching what was generically titled the ‘New Ceramics’, essentially Postmodernism, and Astbury was fortunate to be in the movement’s first wave.

But it was not an easy fit.

The first year was difficult in a new working environment. I did not have enough space, only a desk. It was frustrating and things like scrap yards and industrial tips in the landscape, that had once visually inspired me, weren’t there. I felt lost and at this point nearly left the course. The situation carried on for some time until I started making objects reminiscent of rocky landscapes. A graphics student said they reminded her of Iceland where she had lived and she lent me a fabulous book of photographs illustrating the volcanic nature of her country. I was enthused.

The space issue was solved when Geoff Swindell, a potter and Astbury’s longtime friend from Stoke, a year ahead of him at the RCA, offered to share the studio he had rented and occupied with Mary Keepax.

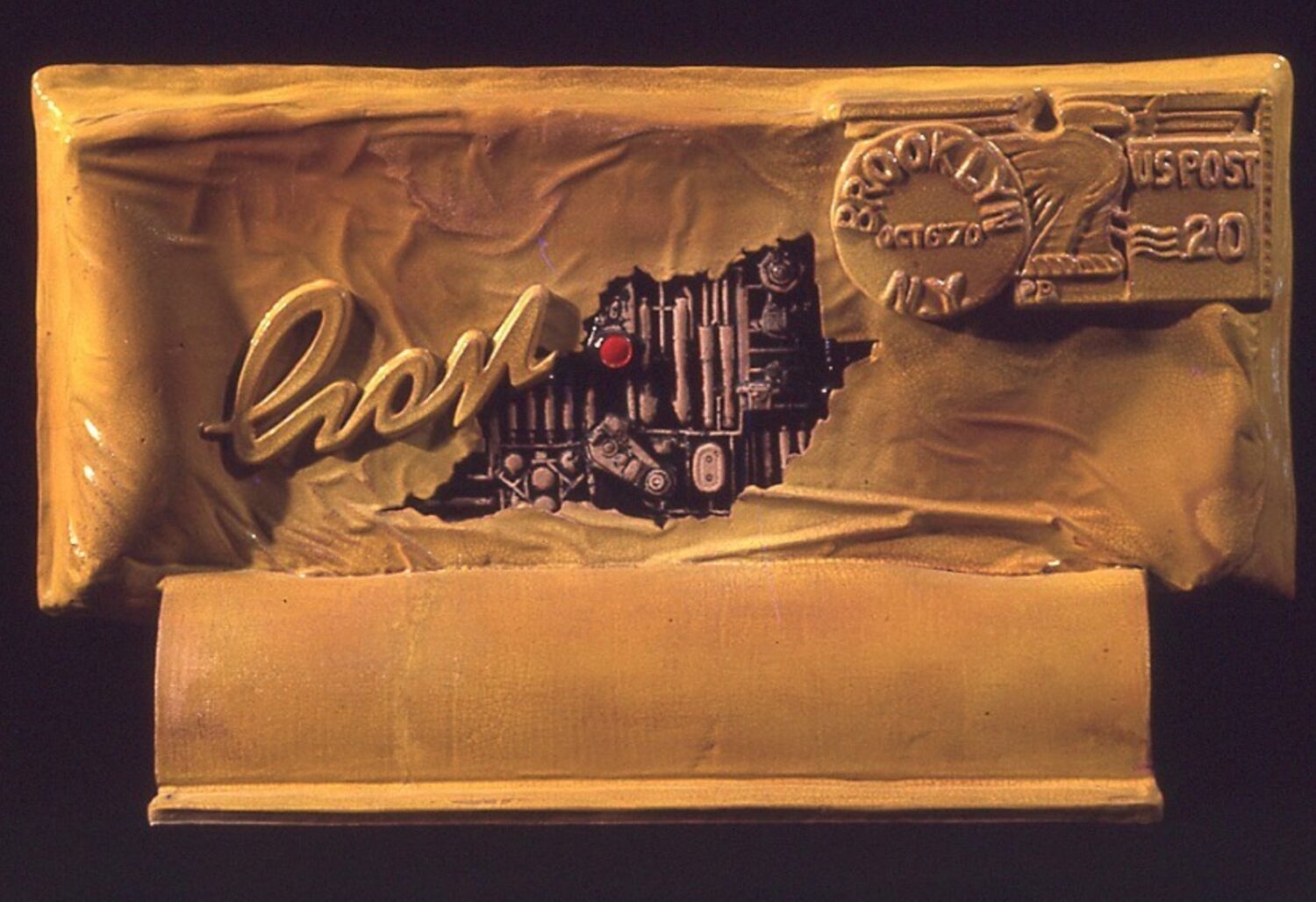

In the second year I felt much happier and started using press-moulding techniques and discovered ways of producing fragmenting surfaces to the clay that gave the impression of aging. Press-molding provided a quicker method of producing clay shapes and structures to develop themes based on obsolescence, fragmenting machines, organic spaceships and other much larger works such as ‘Dog with Mechanical Bone’, and ‘Envelope’.

This was further enhanced when Geoff introduced me to a sandblasting machine in the glass dept. The fine sand, fired at the glaze took the shine off, ate into the surface making it less commercial and much harder to identify as glaze.

In the final year 1971, Peter Aldridge (glass artist) joined me in the studio. Geoff Swindell had already graduated the year before along with Mary Keepax and Elizabeth Fritch. So, for the final year Pete and I had the studio to ourselves. I was asked to exhibit work at Bradford Museum and Art Gallery. I sent eleven pieces and sold four. Next, I received a commission from Liberty in Regent Street, brokered by Queensberry, to make a special sculpture for their Ceramic and Glass Department’s opening.

The RCA was a locus, a place where with Queensberry’s constant prodding, things happened for its students.

By now science fiction had taken over Astbury’s art. This produced a bond with Paolozzi who was also focused on this subject. Paolozzi was a leading British sculptor and one of the founders of the Pop Art movement. His presence in the ceramics department, one of Queensberry’s smartest moves, gave his department a unique link to mainstream fine art.

Paolozzi was a great character and also very enthusiastic about my work and my science fiction focus, heaping gifts on me from toys to magazines, visits to his studio in South Kensington and his home in Norfolk.

This writer first met Astbury with Paolozzi at the Royal College in 1974 when the two artists were collaborating on an exhibition (eventually shelved), Science Fiction in Art, for the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London.

Most of all I enjoyed my chats with Hans Coper. He would come into the studio and I would open the old wooden wardrobe, which contained my small works. He would peer in and give his undivided attention and much valued opinion. On one occasion he mentioned he had had ambitions to be a sculptor too. He loved Cycladic sculpture, an influence that shows in his work.

He responded well always to my work and gave me much support, advising always against teaching. He told me one day that when he was younger returning from Canada after WWII, he had won a residency at Digswell House in Hertfordshire, where he and other young artists were provided with studios to make sculpture. He admitted he failed at sculpture and ended up making clay bricks, which consequently lined the edges of a rough path he made from his living space to his workshop. They were still there when I visited in the mid-seventies. I doubt many people know this. I could have been the first person to own a genuine Hans Coper brick.

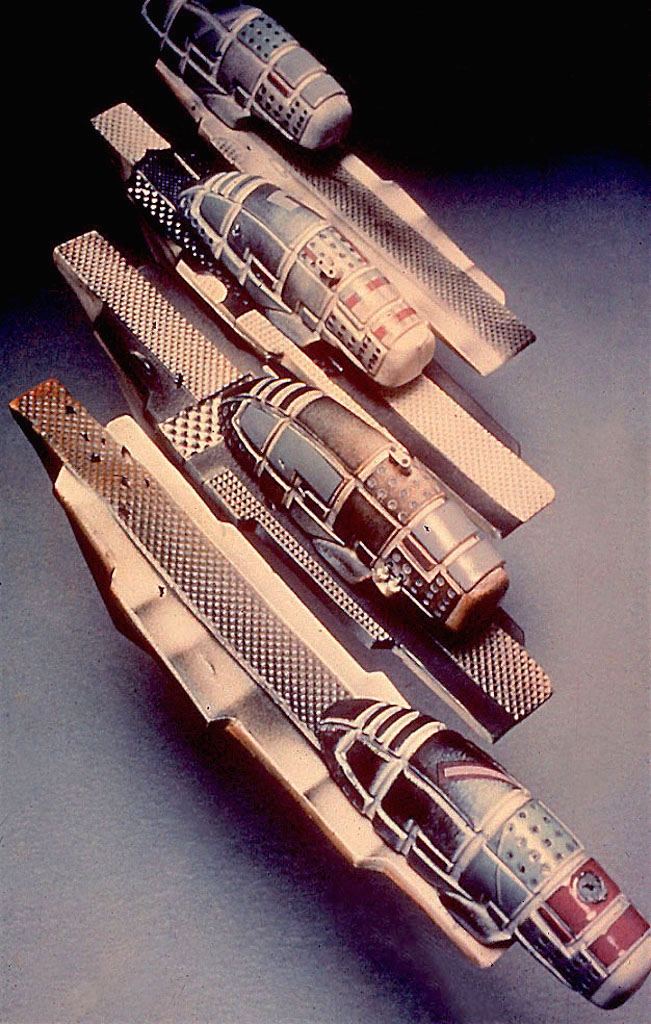

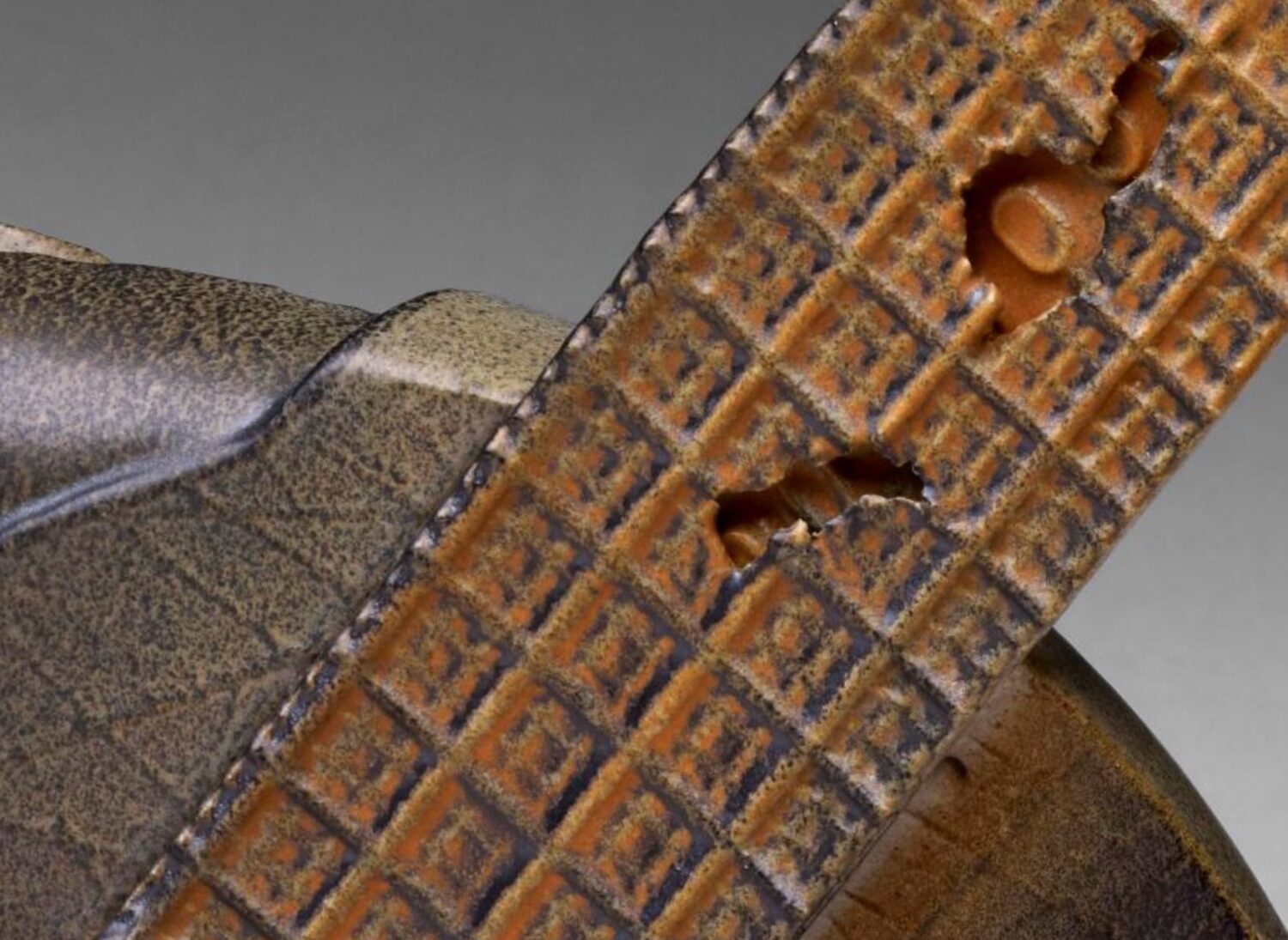

So yes, I was into sci-fi, making clay organic machines, spaceships etc. I also began the series called ‘Synthetic Strata’, rocks split open to reveal fossilized technology, illustrating clay as a by-product of rock and turned back into rock via high temperatures in the kiln.

The work posited Astbury in time travel. He took high-tech components and set them in rocks like fossils, simultaneously part of the present, past and future. As Mark Del Vecchio wrote in Postmodern Ceramics, “Astbury’s work anticipated the post-industrial climate in which we now live. Instead of seeing industry as the progressive future, he projected it backwards into the paleontological past”.

The thing to remember is that it was all to do with impermanence, everything deteriorating and changing and altering values. So yes, there’s a connection between these series but also a difference, particularly in meaning.

‘Fragmentation’ is the falling apart and instability of matter, whereas ‘Synthetic Strata’ is a false alien world of manufactured rocks lying amongst natural ones predating dinosaurs and animal fossils. It puts the future back into the past suggesting re-cycling a whole world programme. I think my work is always involved with this and I don’t mind if you put them together under the one heading, Fossils, so long as distinctions are clearly made.

Certain elements link the series. One is that they all mix organic and technology in ways that range from the profound to the comical. No. 10 Space Form, one of the most evolved of the works in terms of its svelte, elegant process with its soft sandblasted surface, feels like a marine artifact, maybe robotic cuttlefish bone. Or a space vessel.

In all the works the words “alien”, “nature”, “technology (low and high)”, “space”, “rock”, “time” rattle around like divining bones being shaken by a medicine man before being thrown to the ground to tell the future. How they fall, what context they find themselves in, what metaphors they evoke, all change the viewer’s dialogue from work to work.

The last of this decade’s work, represented here by Dual Purpose and Broken Ground, are the most radical. Perhaps they acknowledge and reject a growing preciousness in the art. Either way they mark a shift from refined to raw. The works are broken and poorly reassembled with fragments missing, tape and wood holding parts together and defaced with small-scale penned graffiti. What happens with these works is a shift from conceptual view decay to experiential.

They are the closing coda for a decade-long journey that produced one of the most significant, integrated bodies of ceramic art of the 1980’s. With a new decade the work changes direction and style, recasting Astbury in the 1990’s in the role of a particle scientist and tailor.

Having only read in part the article by Garth Clarke about Astbury.

I am discovering yet further layers, connections and deeper understanding.

I agree wholeheartedly with the tone of Martina Margetts observations.

What’s really struck me; those insightful records and anecdotes.

The lens if you like, for beautifully refocusing Astbury. An individual whose position in the UK will clearly stand in full view. We need a major exhibition.

Dear Garth,

While reviewing Alun Graves’s Studio Ceramics for an upcoming Journal of Modern Craft, I was thinking Paul Astbury is woefully underrepresented in the V&A collection, with just two works, nothing to demonstrate his real significance and achievements – I revisited your CFile to find again your detailed, thoughtful, cogent analysis. How striking Paul’s work is across so many concepts and techniques, and where is ‘Raincoat’, his great piece from the Raw and the Cooked?! Would that the Paolozzi/Astbury sci-fi show had come to fruition and that the Coper/Astbury tutorials had been recorded.

Thank you as always for everything you have done across decades to show us what ceramics are all about, the fundamental creative embodiment of human civilisation.