This is Part 3 of Four Conversations in Lieu of a Retrospective, an overdue exploration of the work, life and career of Paul Astbury, the most important early British Postmodernist sculptor working with ceramics but outside the vessel tradition. Scholarship in the field has failed to record and celebrate his legacy so Cfile has stepped in. You can click here for parts 1, 2 and 4. Quotes in italics are drawn from over four months of email correspondence between Garth Clark and Paul Astbury.

In the late 1970’s Paul Astbury’s focus changed from science fiction to particle physics. He was among the first artists to explore a conceptual fascination with this technology and ever since it has remained a part of his creative practice, his way of thinking, presenting, all the way through to drawing a line.

I was interested in ‘particle accelerator machines’ used electromagnetic fields to whip particles around at great speed, contain them into beams and collide them into one another inside bubble chambers forcing particles to leave tracks and traces of themselves.

The canvas of the bubble-chamber began to appear in his work and took literal form, essentially importing bubble packaging as a kind of porthole (we see this used most directly in his jackets). It was inspired by the way particle physics created “the raw simple marks, expressive fundamental signatures of life. Nature was drawing itself, something we had never seen or perceived in daily life. It seemed to me ‘reality’ was somehow arranged upon an already existing platform or matrix”.

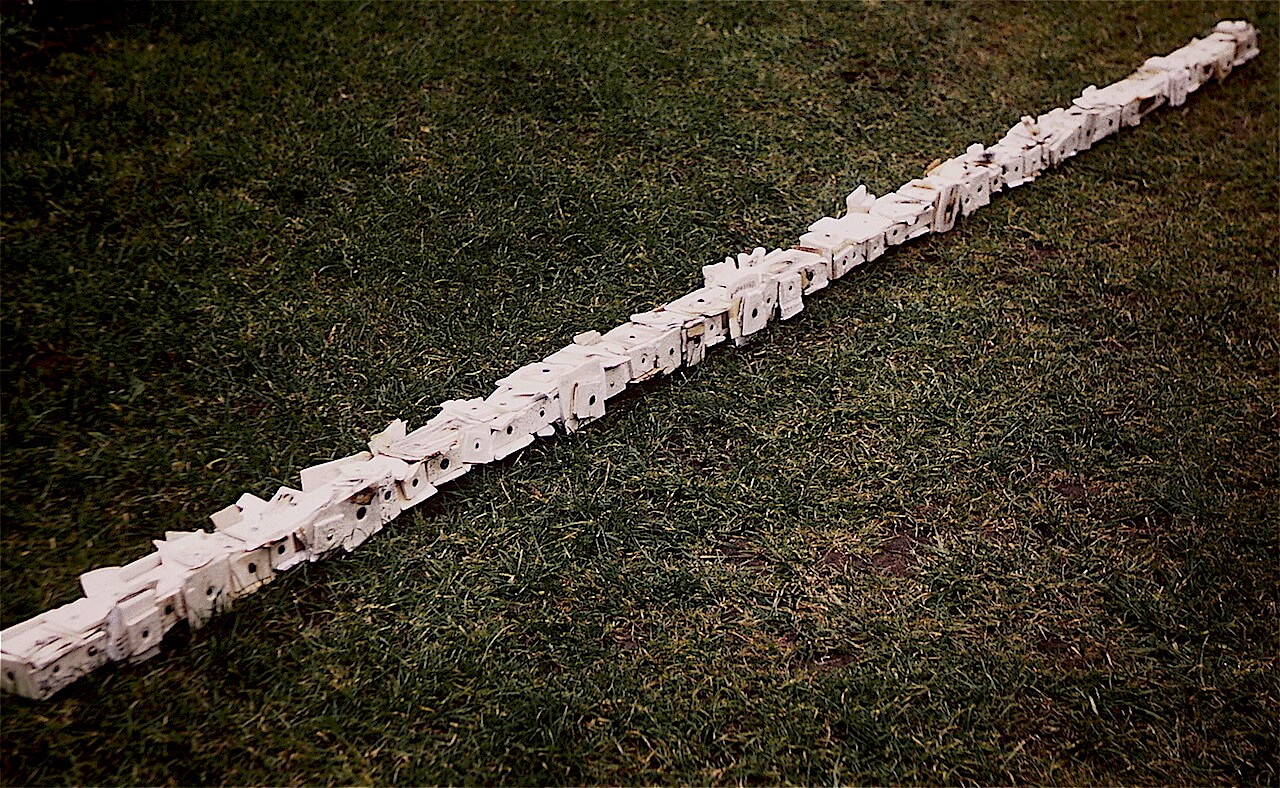

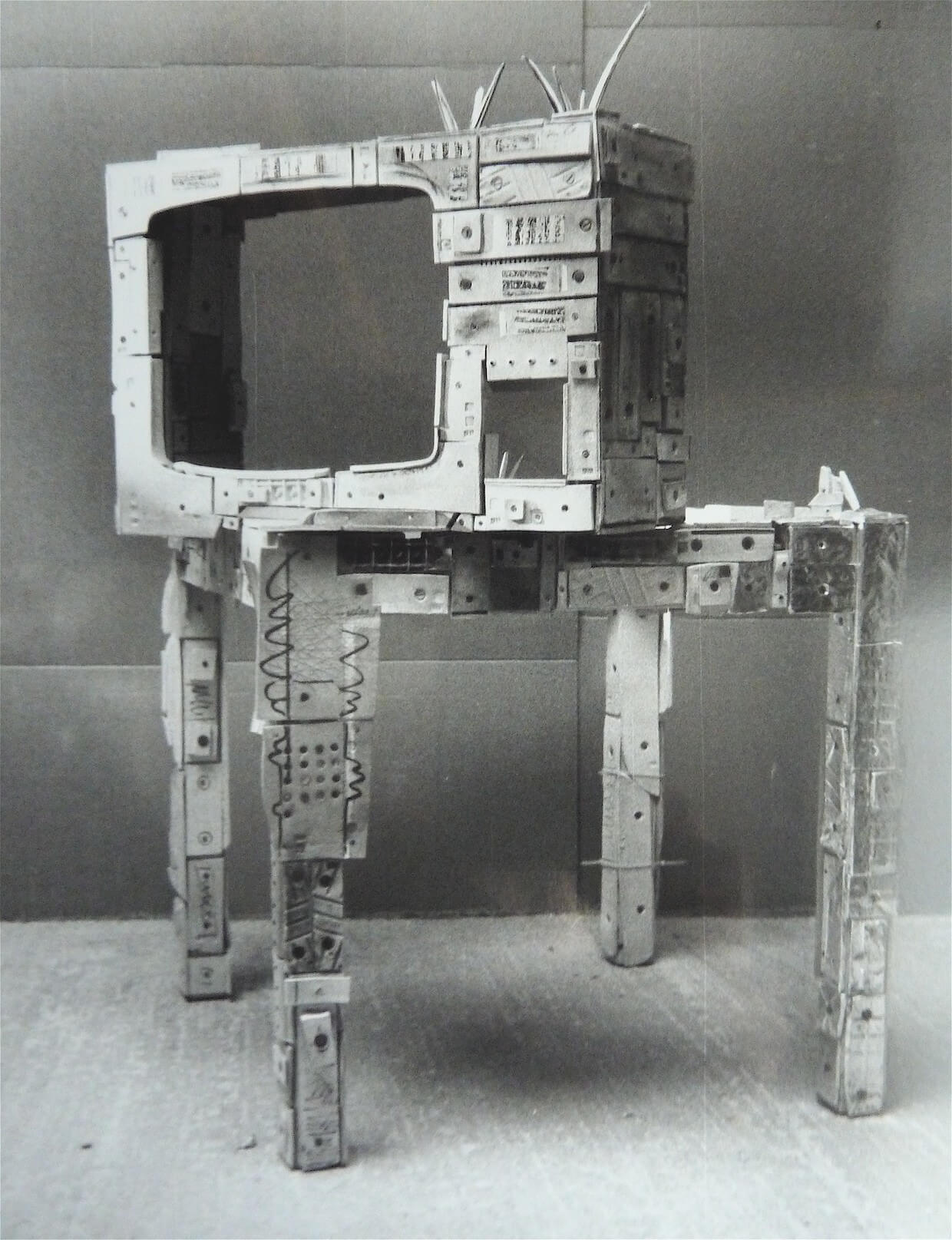

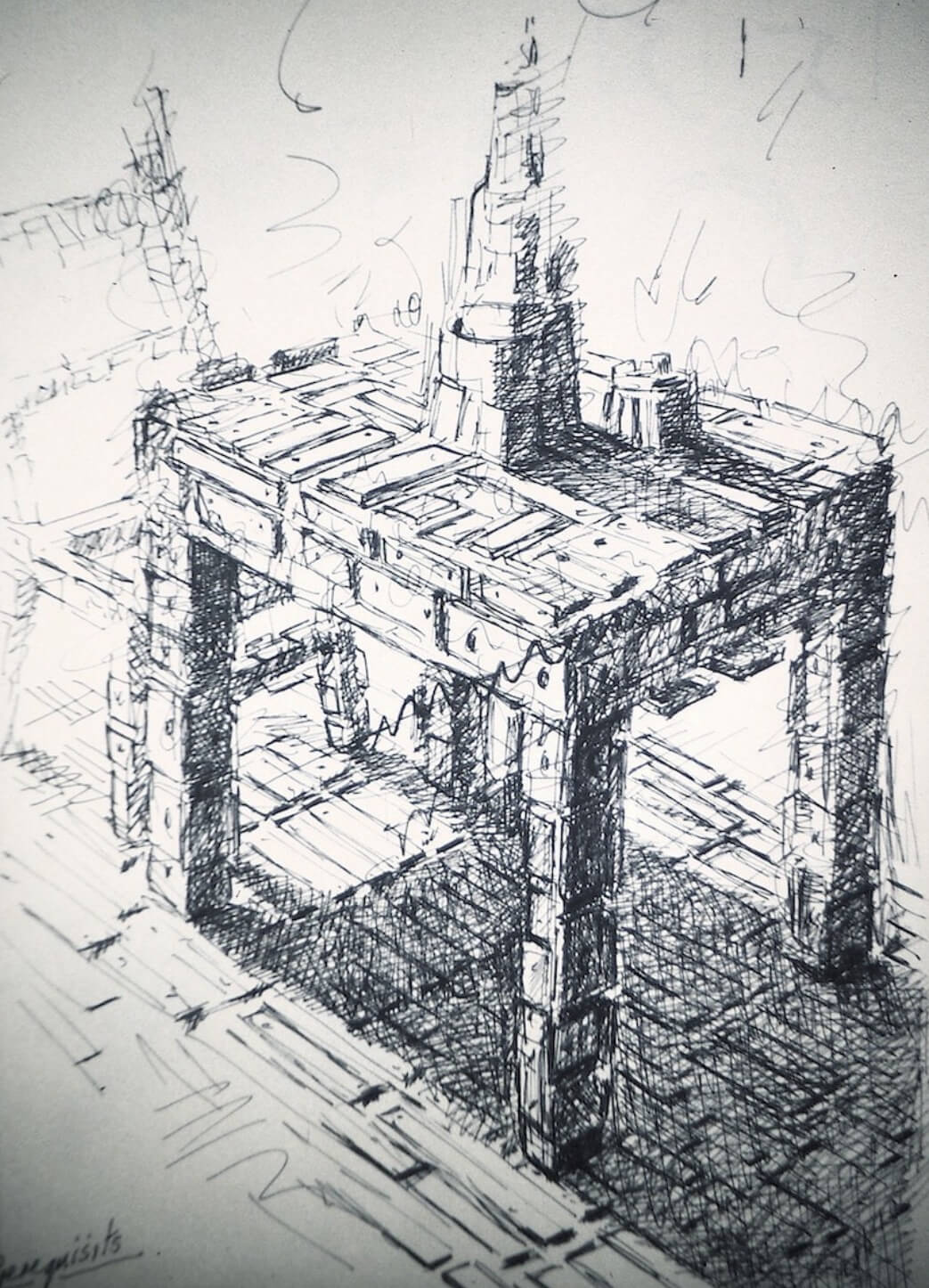

He began fixing pieces of fired clay onto ready-mades, the first being, two lengths of wood, Grown Matrix, 1980, using clay and other materials to illustrate a meeting point between different energies, values, suggesting probabilities of what might have or might not have been. Box (1980), a cardboard box dealt with this in the same way, covered in clay pieces along with paint, sellotape.

Other works followed using tables, chairs, clothing, trees and car tires, etc., things that are involved with our normal daily lives. It was a new way of giving clay “form” other than modelling it and this particular process provided a given structure, chair, table, etc, on which clay could be fixed and exist in space at certain already measured coordinates, maintaining individual position and status. Just as particles carry energy/information, the clay pieces were imbued with marks, colored smears of araldite and burnt oil stains according to my demands.

I realized I was resurrecting each ready-made with new life but also suggesting burial under layers of clay. It was also a tailored encasement of the object, a sarcophagus, a concealed seed. The object’s actual physical reality being retained by this change, a metamorphosis of values allowing it to become something else.

It suggests power and presence of particles rebuilding this world to retain reality of each thing within it. The mind races over such combinations of imagery and those chosen materials in a way that affects perceptions of a structured world, which, to quote Heisenberg’s ‘Tissue of Events’, ‘…connections of different kinds alternate or overlap or combine and thereby determine the texture of the whole’, and to this end maintain as one.

The work Vanished World, 1985, speaks loudest of his particle exploration. It is constructed of multiple collisions, breaks, restarts followed by more breaks taking a brittle material and shattering it again and again. The same anarchic energy and poetic violence can be found in the drawing Drawing/Notebook, 1985.

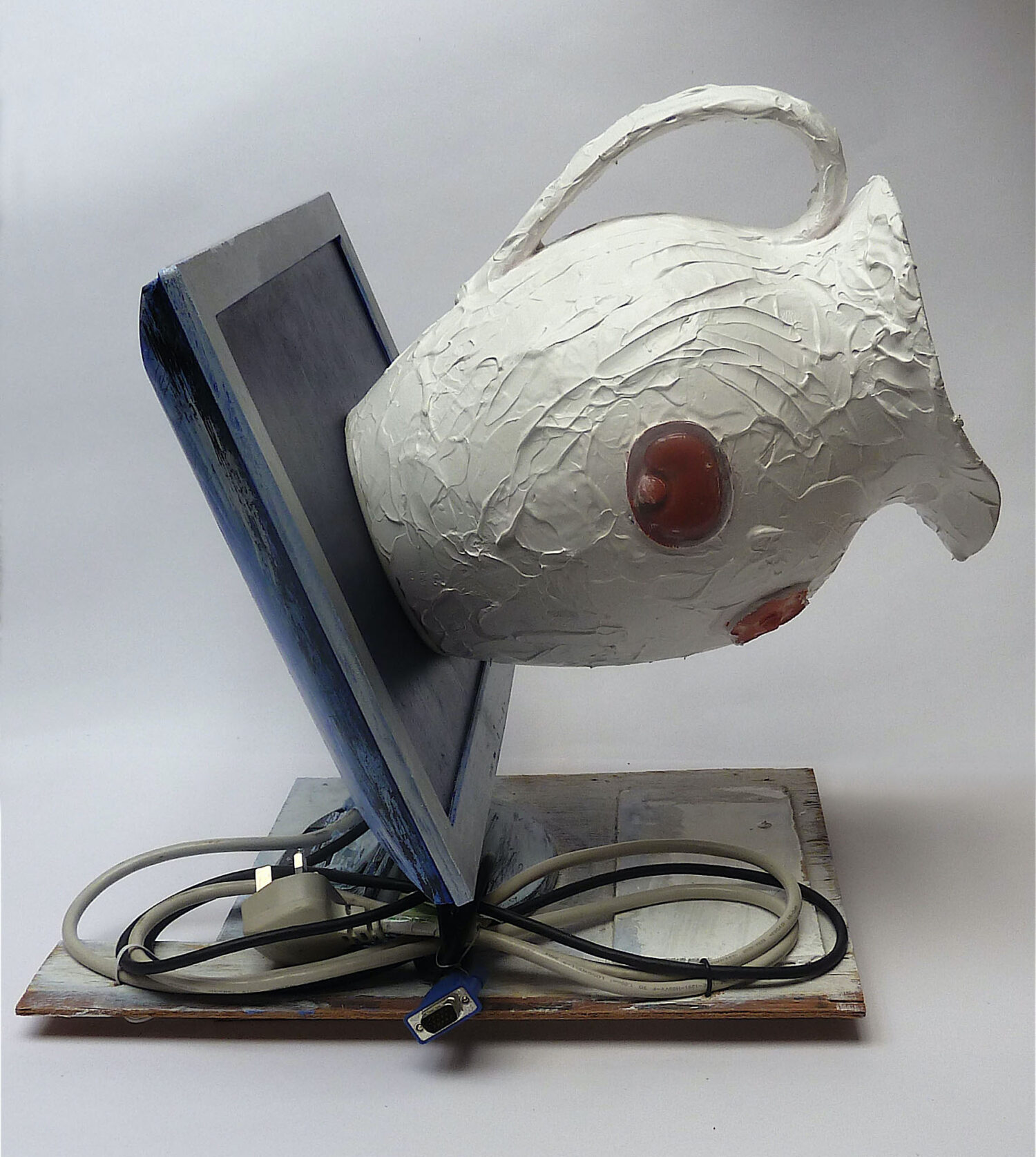

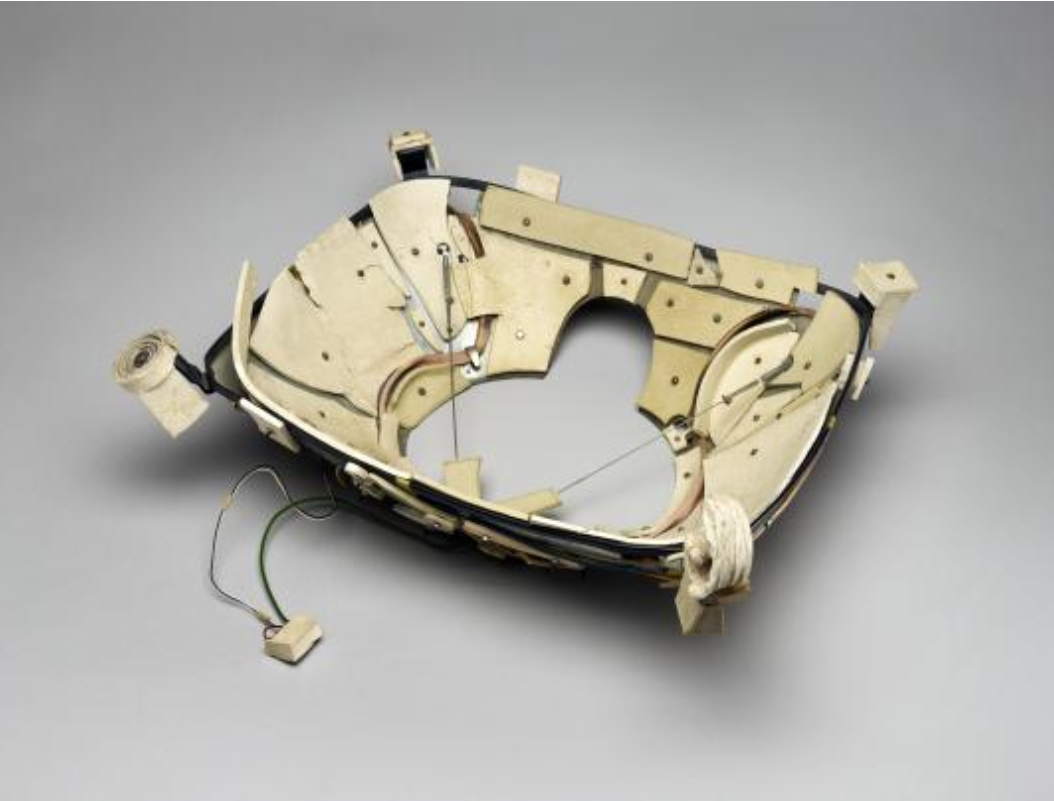

At times Astbury gives into almost comic moments, perhaps to relieve the intensity of this thesis. His layering of art/science metaphors as with Monitor Generating Pitcher or TV Dish (1984), which takes on the ceramic world and the sanctity of the vessel, substituting it with the casing that holds a television tube in place. This cheeky transposition of an industrial cradle, defined by its function to contain, into a pot of importance and complexity, upsets pottery conventions and aesthetics from William Morris to Bernard Leach and to an extent, even those of today.

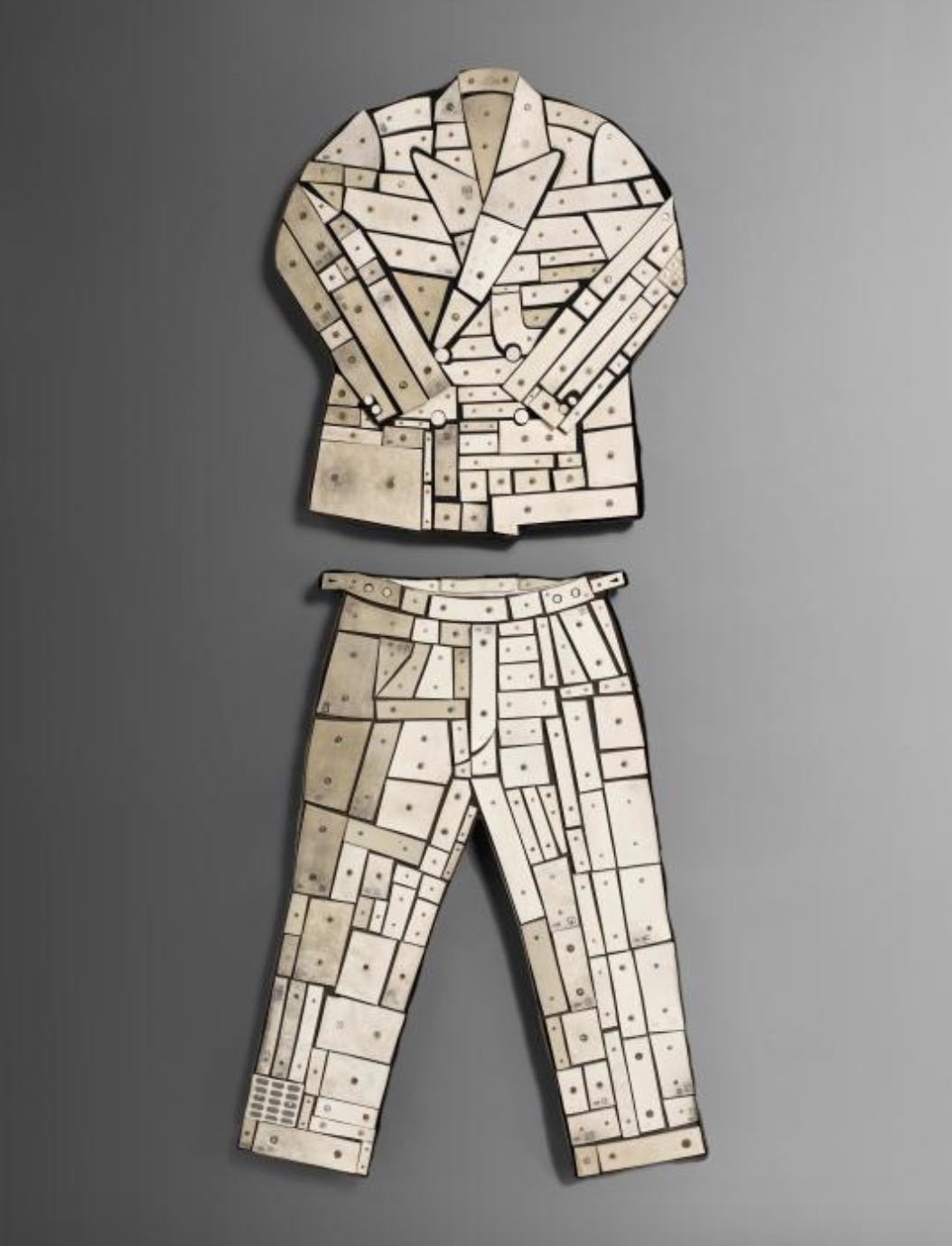

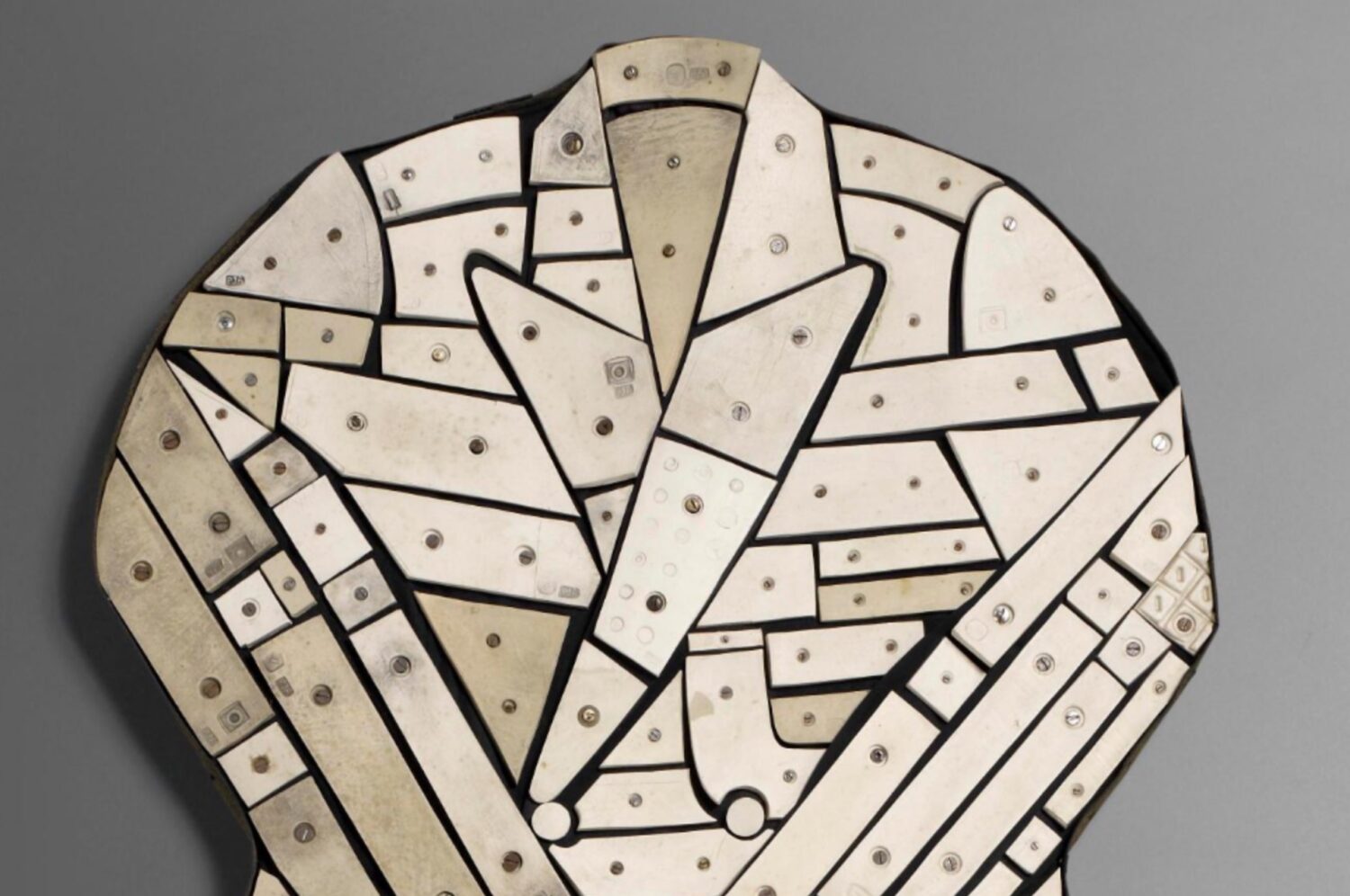

Astbury became drawn to clothing, an on-again, off-again relationship to volume, noting that once we subtract the wearer, garments deflate and become two dimensional. But he also sees clothing as armor, a device to protect or deflect fear.

I began the series of clothing in the mid-eighties with ‘Prisoners Suit’ 1984, representing various concerns, particularly burial. Emmanuel Cooper commented, (Craft Magazine, issue 105 July/Aug 1990) about its appearance of ‘His ‘Prisoner’s Suit’ on the ‘Space and Form’ exhibition, Rufford Park Gallery, ‘made up of neatly cut clay pieces screwed on top of, all but obscuring a pair of trousers and a jacket on a wooden silhouette. For me it is a sinister, intriguing, dialogue on the defining power of convention’.

We hide, bury, trap and protect ourselves inside layers of clothing. Hands and gloves similarly intrigue me, from early mankind daubing cave walls with palms covered in reds ochres or charcoal leaving a signature of personal self. Gloves similarly are indicative of efforts to protect and preserve natural skin from harm or used to enhance as fashion accessories.

The jackets go beyond clay, some are covered with painted images, others in steel and felt. Most are of mixed media but clay is never far away because the many things it represents cannot be ignored. Clothing describes the human figure an echo of activity, presence, stature, office, hopes and fears.

They can be combined with a mass of other things, Between Heaven and Hell, 2010-2019, is a suspended leather suit which supports and uses images made of raw clay on the back of the suit, and fired clay images on the front. These are contained inside a variety of plastic blister packs. I sense the amulet, lucky charms here, representations of the psychological human condition of all hopes and destinies.

For Astbury clothing carries a personal footnote. As a child he dressed better than his family’s financial station would have allowed because his mother was so adept at making their clothes. Though he points out that if one looked closer one would have noticed that the “pants were often patched and the socks were darned.”

Right there as a young child he was seeing clothing as camouflage to alter and improve status. Also, his mother was so supportive of him attending art school, in part, because she had wanted to study to be a tailor but never had the opportunity. While it may be a romantic observation, she left with him part of that unrequited desire, the garment as identity, bespoke but not Saville Row, and since 1980 it has been a continuing obsession.

Add your valued opinion to this post.