Four Conversations in Lieu of a Retrospective turns a long overdue spotlight on Paul Astbury’s career, hopefully the beginning of a deeper examination of his singular and powerful contribution.

These quartet of essays cover some key works from the 20th century but are by no means a full retrospective. That requires a book length treatise. Further, these Conversations only deal with his sculpture and his lively painting career is only touched on when it relates to the 3D.

The informality of illustration, more scrapbook than coffee table, is deliberate because of the range of image quality in the artist’s archives and to be more the roughness of a research document than a finished print project. This has allowed more freedom in chasing the narrative. Paragraphs in italics are from email conversations between myself and Astbury over a period of over four months.

My interest is not entirely objective. I am a fan. In full disclosure: Astbury, and his wife Lesley (to whom this series of posts is fondly dedicated), were among the first friends my ex-wife Lynne Wagner and I made after our move from Johannesburg to London in 1974. I had arrived to invent a career. There were no flesh and blood models for me to follow as a dedicated historian and critic of modern and contemporary ceramics. Astbury’s work and his intellectual acuity and love of debate, was an early inspiration. We have remained friends ever since if sporadically in touch.

I have watched his career ebb and flow, curated an exhibition of his work (solo exhibition Everson Museum 1979) written often of his art in my books (my partner Mark Del Vecchio has done the same) and we have a brace of major pieces by him in our collection at the Museum of Fine Arts-Houston. But I have never represented him which allows me greater freedom to opine.

Click and you can access part 2, 3 and 4.

Let’s begin by imagining a query from an imaginary colleague, a serious arts writer but with little knowledge of ceramics. He asks for the name of the most important early British figure in the growth of Postmodern sculptural ceramics outside the umbrella of the vessel. My answer? Paul Astbury.

The next question is, “where do I find information on the artist; book, survey exhibitions, a retrospective publication?” In truth, aside from one intriguing catalog, Document, published in 1995, there is nothing major. Certainly, there is no retrospective. To younger makers his name rings no bell. The scholarly apparatus of ceramics has totally failed Astbury, and for that matter, the field itself. Nonetheless, he remains a figure of singular importance.

This void was exacerbated by two factors. One is that Astbury never found dealers to support his journey. Where would the artists of Marsden Woo (and its earlier incarnations) be today without this sturdy, dependable, commercial force on their side for decades? Astbury has, throughout his career, lacked a broker. This underlines the central role, often formative, that commercial representation plays in establishing legacy for an artist.

The second factor is that he is a sculptor. By sculptor I specifically and narrowly mean an artist working outside the orbit of the vessel, or more plainly, pottery. The latter covers most of the stars of British ceramic art back in the previous century and even today: Allison Britton, Carol McNicol, Martin Smith, Julian Stair, Grayson Perry, Edmund de Waal, Magdalena Odundo et al. Pot makers all. In British ceramics in the last quarter of the of the 20th century, his disinterest in pottery made him an outlier.

Yes, Astbury did make pots in his undergraduate years. He was in Stoke, how could he not. Throwing did not captivate Astbury at all. And while he sporadically made pottery forms early on, this genre did not lock in. His vessels were mostly slabbuilt, often big, crude, and rudimentary like farm vessels, basins and large angular pitchers, more the forms of metal than clay with lids that suggested narrative. But mostly more sculptor than potter. Little sign of love for the pot.

His approach revealed a fully formed Postmodernist. A plate and a handled pot reveal this. At fifteen he combined lithographic decals with a printed mountain, his defining razor-sharp ironic edge emerging early.

Indeed, this piece, Reclining Vessel (1964), one of his earlier ceramics, shows little reverence for pottery, his droll visual humor presenting more of a grotesquery, a pancake more than a pot.

There is also a period of slipcast vessels made shortly before he left for London that excite. They are nominally pots, however, explosions of shape, line and energy, anchored by volume but not beholden to the vessel.

Tanya Harrod writing in the Spectator says of Astbury that he has “operated these long years as a sculptor but is categorized as a ceramicist…He deserves a big cheer for bravery in defiance of categories”.

Thus, when it came to audience and a place in the ceramic medium, he fell between two stalls; the pot-oriented ceramic community did not get what he did, it was too removed from the decorative arts, and the sculpture wing of the fine arts establishment did not recognize ceramics as a valid medium. He had no home.

Astbury was born in 1945 and raised in Oakhanger, Cheshire, a bucolic gem, a cluster of buildings rather than a village, a mere fourteen miles distant from the federation of six pottery towns: Burslem, Fenton, Hanley, Longton, Stoke-on-Trent and Tunstall. But there was no “Stoke” factor in the Astbury’s daily lives. Rarely visited, it might as well have been in another country.

[Oakhanger] has no shops, no pub, just one Victorian Chapel, a couple of farms, three terraced houses and at that time four bungalows and a wood institute. Real sinister backwoods stuff of the kind David Lynch would die for. I lived in the end one called ‘Affinity’ nearest the chapel. I spent time combing ploughed fields for dinosaur fossils, ancient pottery and Roman treasure. I found a few fossils and bits of farm pottery but never any treasure. Nonetheless, Great days!

Then again, the ceramics scholar might presume that his material choice had to do with family names. John Astbury is one of the great potters of the late 17th century Wedgwood era.

Yes, I did know of John Astbury the potter in my teens, his name was big in the Potteries. ‘Astbury Ware’ as such, filled cabinets in Hanley Museum. But no, not an influence.”

Then came Fradley, Paul’s mother’s maiden name. Was this a possible clue? Thomas Fradley was a drinking buddy of Josiah Wedgwood, a master of marbled slip, and briefly ran a pottery. It was rumored that there were familial links but ultimately neither of the potters inspired Astbury.

The key issue for Astbury growing up was his mother’s amateur pursuit of art. Mrs. Astbury had worked for a well-to-do woman as her maid and companion before the war. This gave her interests and values not usually found in what was essentially a working-class family. Mr. Astbury had owned a coal transport business before the war but afterwards worked as a laborer for British Rail.

When her employer died Mrs. Astbury inherited a sum of money that allowed her not to have to work as well as providing inherited quality furnishings. Together with a house they owned, this gave the illusion of being mildly well off when in fact money was always short, worsened by Mr. Astbury’s gambling habit.

On my mother’s side of the family there is a history of bargees and boat building at Chester, making barges for the canals and painting and decorating of the barges themselves. My mother’s uncle Tom did this as a living, wonderful decorative motifs of castles and roses.

My mother began my drawing while I was still in my highchair. Placing a matchbox and coin into my small hands, she showed me how to draw around them to create basic images of cars, tractors and motorcycles. I was very keen to learn and by the time I entered school was able to impress all teachers with my range of drawing skills. Unfortunately, that’s all I could do and the rest, my required CGE’s, was a hard slog.

In 1963, at the tender age of 15. he was admitted to the Burslem College of Art School for a pre-diploma course leading to Art and Design (Dip. A D) majoring in drawing and painting. That might have been his future but for a eureka moment.

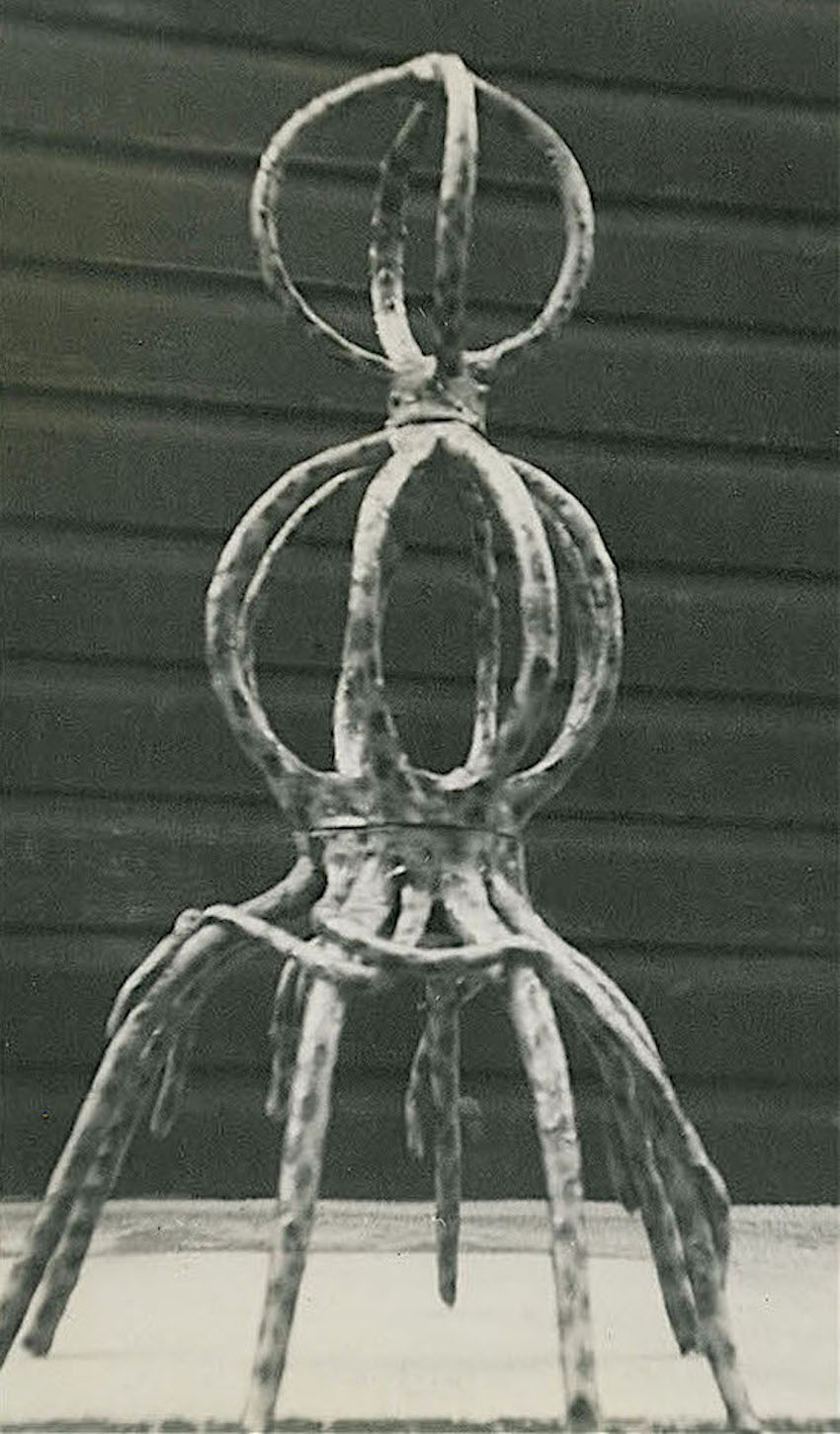

By chance one lunch hour I noticed Colin Saunders a young tutor, working in a room I had never been in before. Curious, I entered to see what he was doing. He had a plaster mold in front of him and from this he was trying to extract something. The ‘something’ turned out to be a piece of slip-cast clay. I was familiar with wheel-thrown pottery but not this. The clay image turned out to be a twig he had molded and cast to make an unusual cup handle. I thought, ‘instant metamorphosis’!!

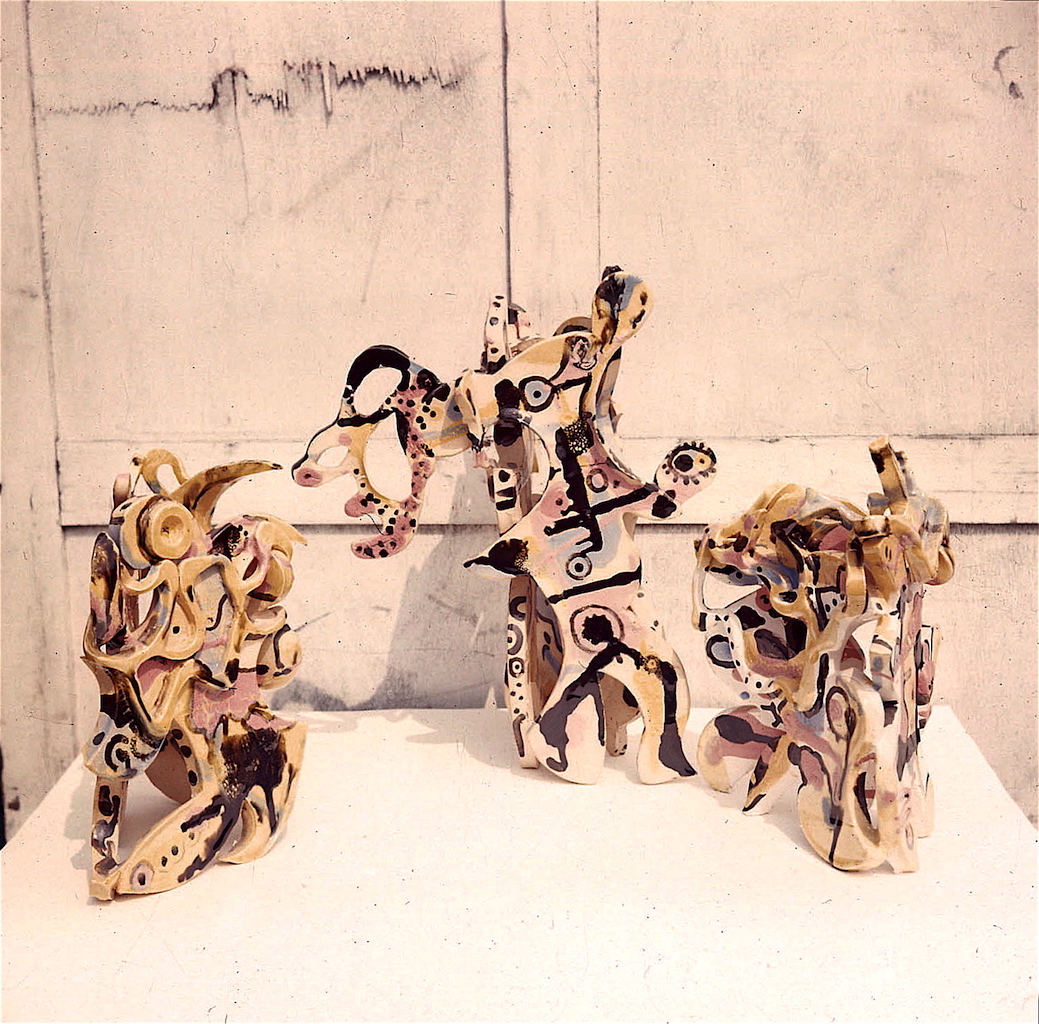

I asked if he would allow me to use and experiment with clay in the same way. He agreed I could work in the room with him every lunch time. I made many clay pieces during this period and flabbergasted myself and him also by the images produced, such as ‘Octopus’.

Structures like ‘Octopus’ were something new in ceramics, well, in Burslem at least, and building it involved balloons, never associated with ceramics either, that gave it support while the minor miracle dried and shrank as the balloons withered relative to the clay. How could such delicacy survive a firing without falling to pieces? Well, it survived two firings, a bisque and another for the glaze and this was all thanks to quality engineering.

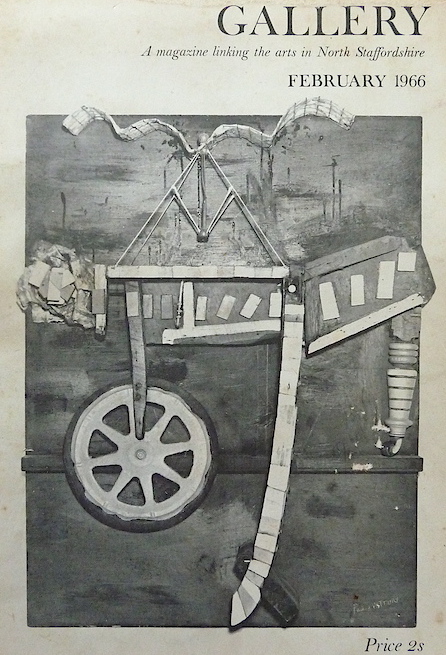

From the moment Astbury entered school, he was eager at his young age of fifteen, to yank Modernism’s chains. Later works such as Flat World (1968) and The New World (1968) sent the same message.

He found a loyal champion in the school principal, Reginald Marlow, who had a ceramics background. He was a ceramics graduate at the Royal College of Art, London, under Professor William Staite Murray, and a competent potter.

For Marlow, Astbury was a perfect student to show off the school (note the image below with Marlow and Lord Snowden); working-class, handsome, charismatic, smart, eloquent, progressive, edgy, questioning and forceful.

In 1965 Astbury was invited to join the BA program in Stoke-On-Trent by the Head of Fine Art, Colin Melbourne.

I had intended doing a B.A. Fine Art in Painting but quickly realized clay had more to offer though I continued with painting as well which proved useful. For one thing it was wide open for the fine artist to explore and challenge the status quo. Melbourne also saw the opportunity and I was his point man.

There was no money, local authorities would not pay further fees. As fate would have it, there was a painting competition in the college, called ‘Nocturn’, and I won. ‘The British Pottery Manufacturers Federation Award’ provided my tuition fees for the whole year ahead plus all expenses and materials.

They were great days in many ways, hard, heady and slightly on the wild side but first and foremost always aimed towards the practice of art.

His next stop (and the next conversation) is in 1969 at the Royal College of Art, London.

I was taught by Paul at Cat Hill 1972 -1974 long before he became Head of Ceramics. He brought the influences of the RCA to us especially Eduardo Paolozzi. His influence led me to start incorporating mould marks into my blown glass sculptures in the glass studio at Cat Hill during 1973 – 1976. He is a great inspiration, sculptor, and lecturer.

Dr Paul Margerison PhD, MSc, BAhons Middx, Cat Hill.

Reading this article – having missed the original; struck by it’s insightful tone.

It’s now 2024.

I’m unaware of a Retrospective of Astbury as yet?

I was taught by him in the 1980’s. Middlesex Polytechnic.

How fortunate am I!

Thank you

Loved it!!!!!!!!!

Between painting and clay work.

Loved it!!!!!!!!!