OXFORD––Pioneering Women, on view at Oxford Ceramics Gallery (14 February – 27 March 2021), features 40 works by 10 pioneering female artists. The exhibition celebrates the significant contribution this group of artists has made to the development of contemporary ceramics, with a focus on the vessel form. The exhibition will now open at the gallery from April 12 until May 1, 2021 and it is possible to see the show by appointment.

From trailblazing figures such as Lucie Rie and Ladi Kwali to Bodil Manz, Magdalene Odundo and Jennifer Lee, the exhibition reflects a broad interpretation of formal ceramic traditions. Vessels on display range from Japanese clay work and the domestic pottery forms of Denmark, Korea and Nigeria, to works influenced by European movements such as Bauhaus and Postmodernism. Even so, as Florence Hallet writes:

Domestic function, and the potential for vessels to serve as womb metaphors, have created an association with female experience, but the examples here warn against comfortable categorization. Akiko Hirai (b1970) specializes in Korean moon jars, but in her hands this traditional vessel slips the constraints of domesticity, with organic forms that look as if they might have emerged direct from the ground.

Florence Hallett for inews.com

The artists span three generations, from Viennese-born Lucie Rie (1902–1995) to Japanese-born Akiko Hirai (b. 1970). Rie, with her refined thrown and glazed domestic vessel forms, brought the unmistakable aesthetic of European modernism to the UK when she fled Vienna in 1938.

It is hard to put into words what I so love and admire in her work. It might include the way that her sgraffito drawing opens up the space inside and around bowls or the drips of bronze manganese sliding down the surface of a white glaze. Her mastery of glazes allows her to use beautiful, unexpected colour combinations which draw me into her world and (particularly with the yellow works) seem to reflect the whole history of refined but intimate ceramic objects.

James Fordham, 2021

Hirai, who is now based in London, re-interprets the traditional Korean Moon Jar form (originally an everyday storage jar) through combined coiling and throwing. This technique offers a contemporary take on the Korean tradition which is influential within the modernist school of studio ceramics.

You sometimes find a connection between two or more things that appear to be completely irrelevant. We do not usually try to find these puzzles because they are hidden beyond our consciousness. We do/can not see them as they do not exist, yet occasionally there are events that trigger that sense of connection. It is almost shocking when this sensation is awoken.

When it happens, we call it “coincidence”. I believe these coincidences are led by the incompleteness of the events. In the world of physics, everything moves towards a balanced form and completion, as does our state of mind. When you see something that is not “quite right”, your eyes automatically try to adjust it, to almost make it look right. How do we know the balance? But we do.

I try to put similar thoughts of mine into my ceramic pieces. They should not have a clear message as they are supposed to fit somewhere into the users’ mind.

Akiko Hirai

Another development of European modernist form can be seen in the work of Danish designer Bodil Manz (b. 1943). Manz’s precisely constructed cylinder vessels make use of industrial ceramic techniques such as slipcasting, mouldmaking and transfer printing to create simple translucent forms.

A ceramic artist once said, “We are romantics of material” –the materials seduce us.

In recent years I have been working on a very simple cylinder in porcelain where the transparency of the body allows the light to show the compositions made up by decorations both on the inside and on the outside of the cylinder.

To me the cylinder is like a sheet of paper on which I can do different things depending on where I am in life. That is why I do not get fed up with them.

Bodil Manz

The hand-built hollow clay forms of Dutch artist Deirdre McLoughlin (b. 1949) reflect her time spent working with the experimental Sodeisha group of Japanese artists near Kyoto, in the early 1980s.

I began my journey with abstract, open forms. In 1978, closing over a sculpture for the first time, I recall my trepidation in the act. The forms stayed closed for 20 years. While living in Kyoto I came on the anecdotal story that it took Yagi Kazuo four years to close the vessel form so that his works could escape into pure expression and be free.

In 1999 I was ready to explore the idea of the inner space in my works and to this end I opened up a small ovoid giving it some attitude with a forward foot. I hoped that if I made this form over and over it would allow me an understanding of the space within – I saw it as a koan. Eventually I found the key in an essay by the art critic Peter Schjeldahl and understood that I must build around space. Up to this point I had been building into space.

Deirdre McLoughlin

Similarly, the winner of the 2017 LOEWE Foundation Craft Prize Jennifer Lee (b. 1956) studied Japanese traditions and techniques during residencies in Shigaraki, a period which deeply influenced her subtle earth-toned works.

However, my making methods have changed little over the years and my work continues to be concerned with a relationship of materials in the studio…I have developed a method of colouring the clay by mixing in metal oxides before making. I use no glaze or surface decoration although one of the early pots on show, from 1987, is burnished using rusty metal. In almost all my work colour runs through the pot rather than on its surface so form and colour are integrated.

I am fascinated by the way oxides react with each other: in certain circumstances they migrate from one band to another producing halos. Through testing and re-testing, I’ve discovered that some specific mixes alter and change over time. The speckled clay, in the most recent pale stoneware pot exhibited, was mixed over thirty years ago.

Jennifer Lee, London, February 2020

Japanese influences can also be seen in works by Danish artist, Inger Rokkjaer (1934– 2008) whose vessels meld a subtle use of raku with homage to the earthenware domestic pottery of her native Jutland, Denmark.

At Aarhus, studying with senior Danish potter Gutte Eriksen, who had visited Bernard Leach in England and studied in Japan, Rokkjaer absorbed the contemporary fascination with Japanese aesthetics in ceramics. It was here that her life-long exploration of the Japanese-originated technique of raku firing was born even if, as many have commented, the robust lidded jar forms for which she is most known owe more to the red earthenware traditions of Jutland pottery.

The unusual aesthetic of British artist Carol McNicoll (b. 1943), who originally trained in fine art, makes inventive use of industrial ceramic techniques. Combining her artistic knowledge of collage and textiles with slipcasting she creates patterned surfaces and coloured, constructed, domestic forms intended for everyday use.

I use the process partly because of its mimetic capacity, but mainly because the work both operates within and comments on the ceramic tradition as expressed within the domestic context. All my work is functional. I make things that I want people to use, it seems to me that for most of the second half of the twentieth century artists have abandoned the home as suitable context for art, I am interested in reversing that trend.

Carol McNicoll

Together with fellow British artist Alison Britton (b. 1948), McNicoll came to prominence as part of a group of female RCA graduates in 1970s London. Also known as ‘The London Ladies’, they were commonly identified with Postmodernism due to their free juxtaposition of formal traditions. Britton’s square, asymmetric vessels embody her characteristic fusion of painting and sculpture. These hand-built, large-scale forms explicitly reject the dominant, circular form beloved of modernist potters such as Rie.

I realised the value in showing pots from different working phases together. In this spirit I decided, for ‘Pioneering Women’, to include a piece from 1991 and one from 2015 with new works made for this show. The language of the existing pieces, especially the oldest one, furthest from the way I work now, has steered my approach to the new pieces.

In a long conversation with art and craft, and histories that are both cultural and domestic; the pleasures of slow making, loose glazing, and re-firing, hold my hope for sparks of the unpredictable.

Alison Britton

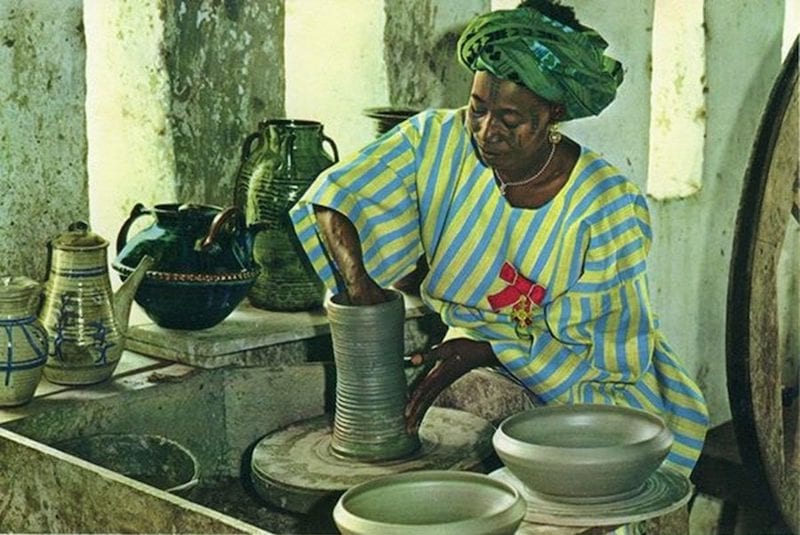

Works by Nigerian artist, Ladi Kwali (1925–1984) combine throwing and hand- building, revealing her immersion in both African and European traditions. The latter was honed at the Abuja Pottery School, Nigeria, under English studio potter Michael Cardew in the 1950s.

Kwali learnt to make pottery as a child with her aunt, who worked in the Gwari region of Northern Nigeria, an area that is home to a highly valued and important female ceramic tradition of handbuilt low fired earthenwares. Kwali was recognized early on as a skillful and imaginative potter, becoming the favoured court artist-potter for the Emir of Abuja. It was in the Emir’s palace that English potter Michael Cardew first saw her work prompting him to invite Kwali in 1954 to become the first female trainee at his Abuja Pottery Training School (est. 1952 ). He taught her to throw on a wheel, and to explore the potential of glossy high temperature stoneware vessels. Despite becoming a highly skilled thrower, Kwali preferred her traditional method of handbuilding works positioning a pot on a stool or low table and walking around it, coiling the clay and thinning it as she went. However she combined this approach with striking glazed surfaces, incised with her own abstract/naturalistic drawings, assimilating the Abuja training with her own highly versatile traditional practice finding a strong, individual voice in the process.

In 1974, Cardew introduced Kwali to Magdalene Odundo (b. 1950). Working with Kwali, Odundo studied the traditionally female art of making utilitarian pots in Africa, as well as practical techniques like hand-building.

What is astonishing about Ladi Kwali, is that, she was able to maintain her individual style by remaining faithful to her unique fable like, story telling narratives with symbols drawn from the natural world that were the hallmark of her decoration.

Magdalene Odundo

Odundo used her experience with Kwali in Nigeria to develop her independent approach to ceramics, originally fostered as a student at Farnham School of Art. Her powerful, red and black clay vessel forms reveal keen understanding of the hybrid nature of ceramic art forms.

I am deeply interested in the human body and its symbolic associations to various ideas of beauty and spirituality. My vessels often have tactile qualities that emulate the sensuous landscape of the body in particular the female body.

Pottery is associated, in many world views, with woman’s role as a container of life. In African myths of genesis, for example, the creation of human life by a supreme being, is directly linked to the work of the potter, who moulds a vessel from earth, water, fire and air into a beautiful, lively form. Clay vessels therefore serve as sacred containers during rituals that link to the spirit world.

So, in some sense, my vessels simultaneously embody the image of woman, the womb, the creation of life, and the link between the spirit and human worlds.

Magdalene Odundo

The above is merely a teaser. Oxford Ceramics Gallery has produced an excellent catlaog that fully surveys this sprawling show. View the catalogue here.

Text (edited) and images courtesy of the Gallery.

Heel erg van genoten!! BEDANKT!