LAMBERTVILLE, NEW JERSEY—Modern Design was held at Rago Auctions last week on 12, September, 2020. It has been watched closely. In a sense it was viewed as the canary in the mine.

Would the market for modern and contemporary works hold given a raging pandemic, political instability, lockdown, and the worst economy since the Depression? The trend was downward but, in most cases, so slight that it says nothing about long term viability. The results were mainly good in that most prices held, no unexpected highs, but lows were perplexing. At least it was not a rout as some had feared.

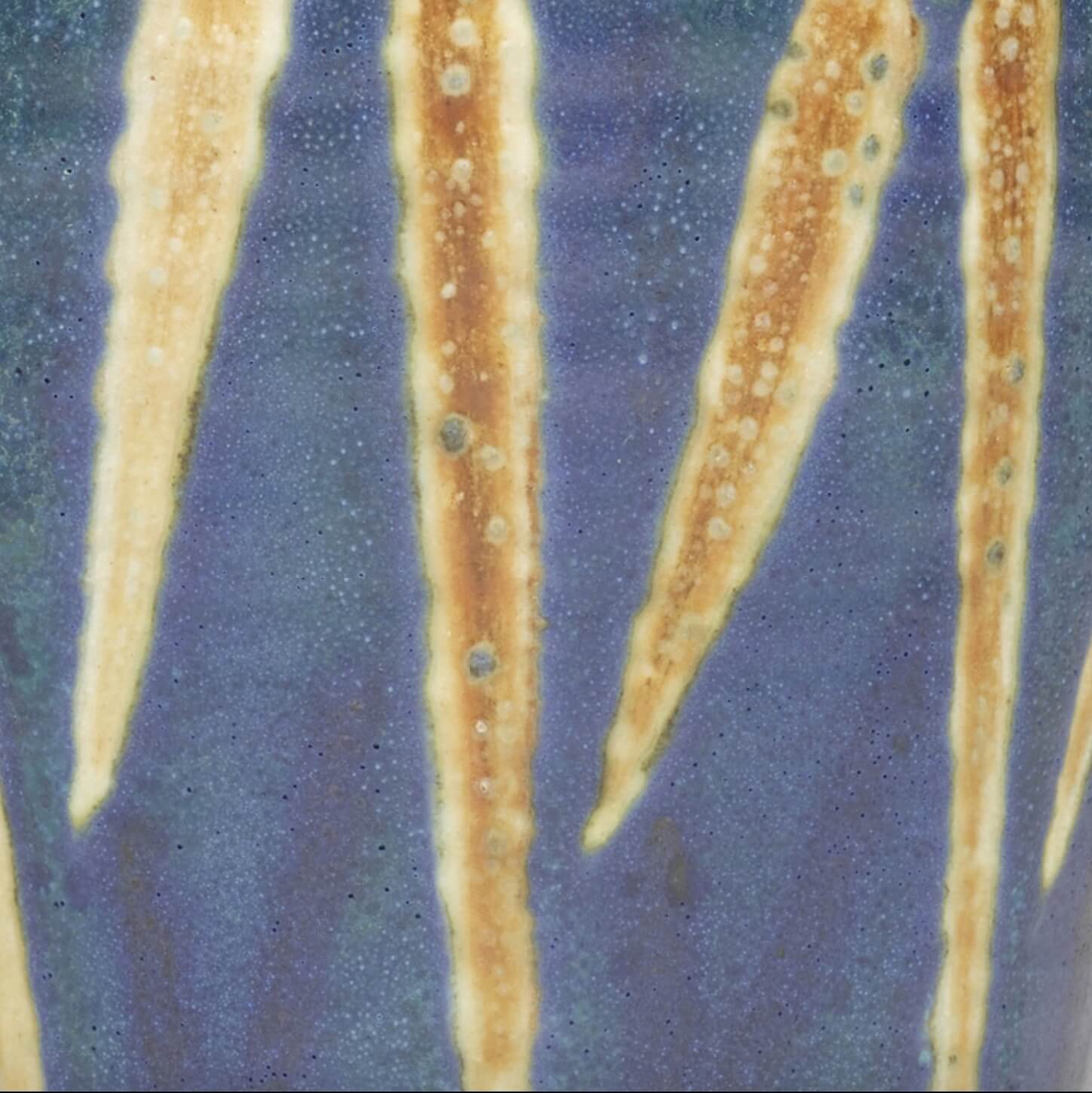

Maija Grotell

Vase

c. 1955

Estimate: $1,000-$1,500

Result: $1,350

It was a good group of work, with the prestigious highlight being an excellent group of plates and pots by Peter Voulkos. This will be discussed in part two with other contemporary work. In this section we look at more traditional work.

Estimate $25,000 – 35,000

Result: $225,000

The potters here have been taken in under the design umbrella and it is the best thing to happen to studio pottery. Unlike the xenophobic craft market, design is truly a international, cosmopolitan activity with a very broad audience of wealthy collectors, often discerning and a tad more scholarly. Moreover, they were not hung up only on material and process alone. And they have deep pockets not hesitating to pay $225,000 for a four and half inch cup by Lucie Rie on Phillips Design Auction (29 July 2020) or close to half a million for Hans Coper vase.

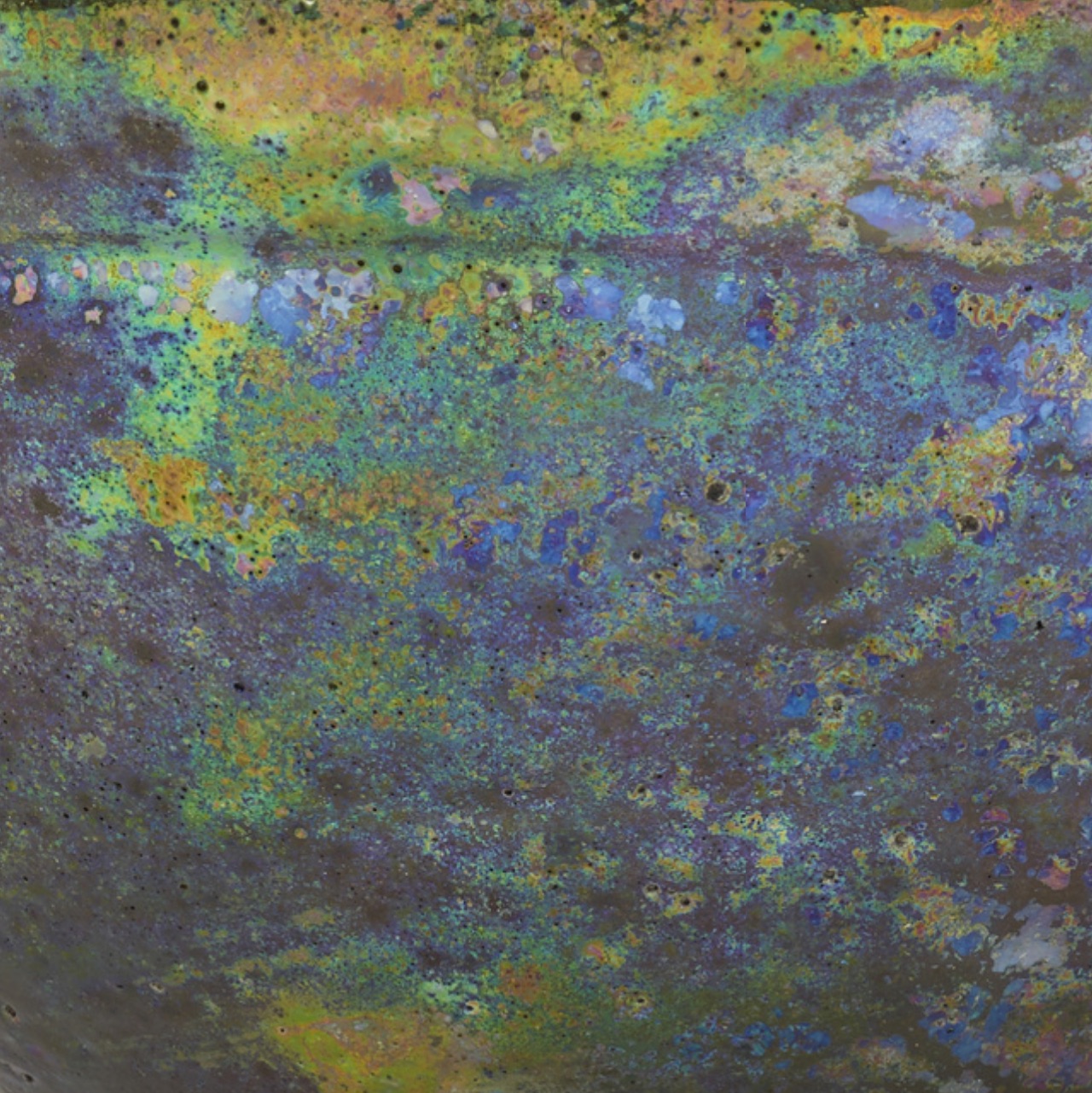

Beatrice Wood

Folded Bowl

Estimate: $1,500-$2,000

Result: $2,000

Beatrice Wood

Bowl

Estimate: $1,800-$2,400

Result: $2,500

Beatrice Wood

Chalice

Estimate: $2,500-$3,500

Result: $8,125

The funky pots by the Mama of Dada, Beatrice Wood, are moving up in value slowly but are still underpriced for this art world legend who was part of Marcel Duchamp’s Dada Circle in New York, working until her death at 105.

Bidders usually go only for her regal luster works. Now more attention is being paid to her volcanic glazed pieces (which she learned from the Natzlers with whom she briefly studied in the 1940’s leading to the end of their friendship).

Edwin and Mary Scheier

Early Chalice Form

c.1955

Estimate: $2,000-$3,000

Result: $1,760

Edwin and Mary Scheier continue a gentle downward slide in prices. They are exceptional potters and have been an auction staple for some time. The Scheiers moved to California from New England (cold weather is not the potter’s friend) emphasizing just how much of a magnet Southern California was for ceramists in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s. The couple never embraced Modernism and remained anchored in their stylized 1940’s look for the duration of their careers.

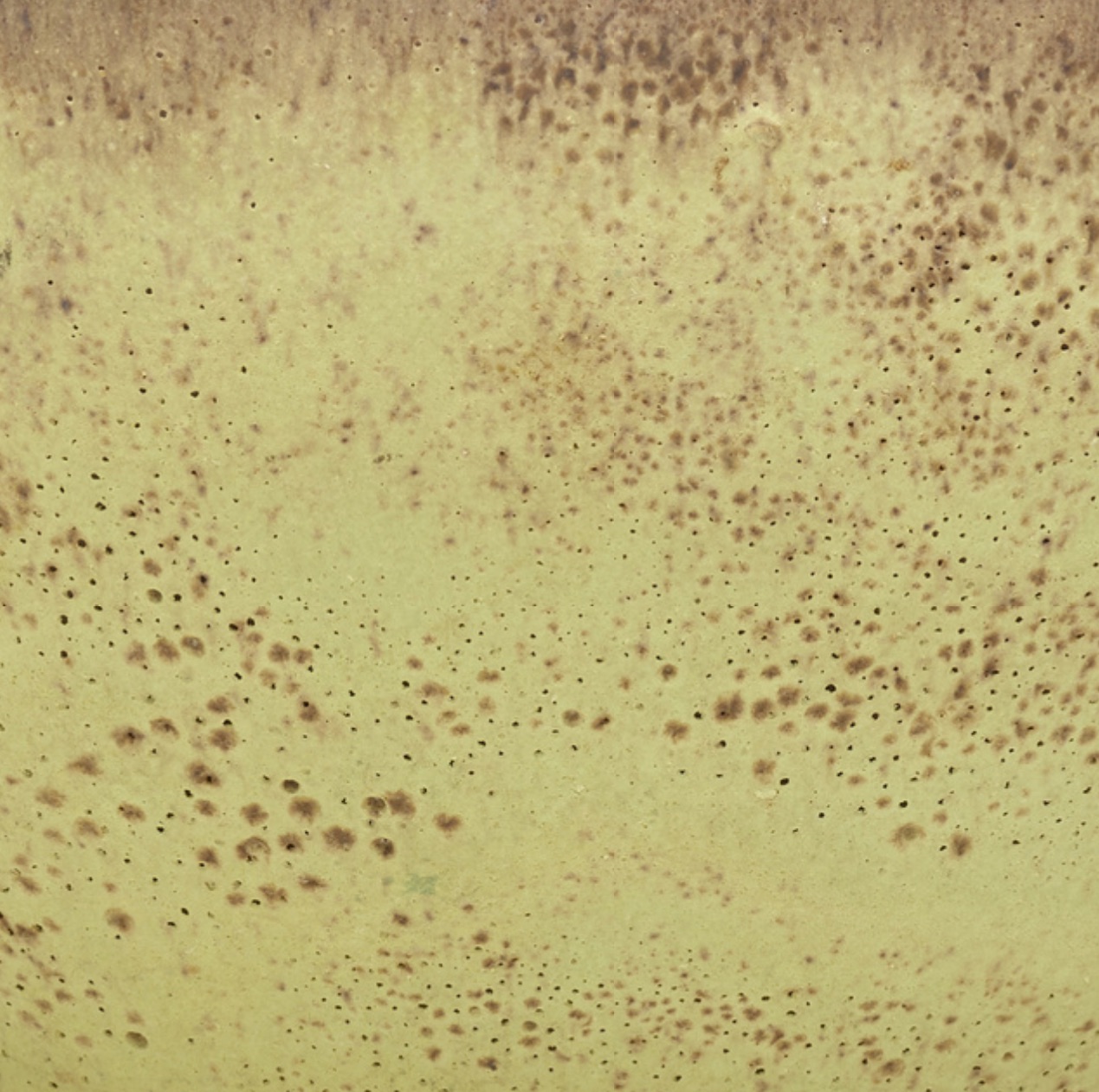

Peter Voulkos

Early Rice Bottle

c. 1953

Estimate: $3,000-$4,000

Result: $4,688

Peter Voulkos’ early functional pots, made from 1947 when he joined the University of Montana until 1954-55, have been placed here to make a point. These pots, because they are not part of his more radical Abstract Expressionist work post-1955, have long had a hard time gaining market traction. This is changing fast.

Now they get decent prices (expect these to keep growing) and collectors are realizing just how accomplished these decorative wares are, heightened by Voulkos’ precocious precision on the wheel.

But as you can see here, this work was not yet innovative. It meshed seamlessly with other conservative functional pottery being made at time.

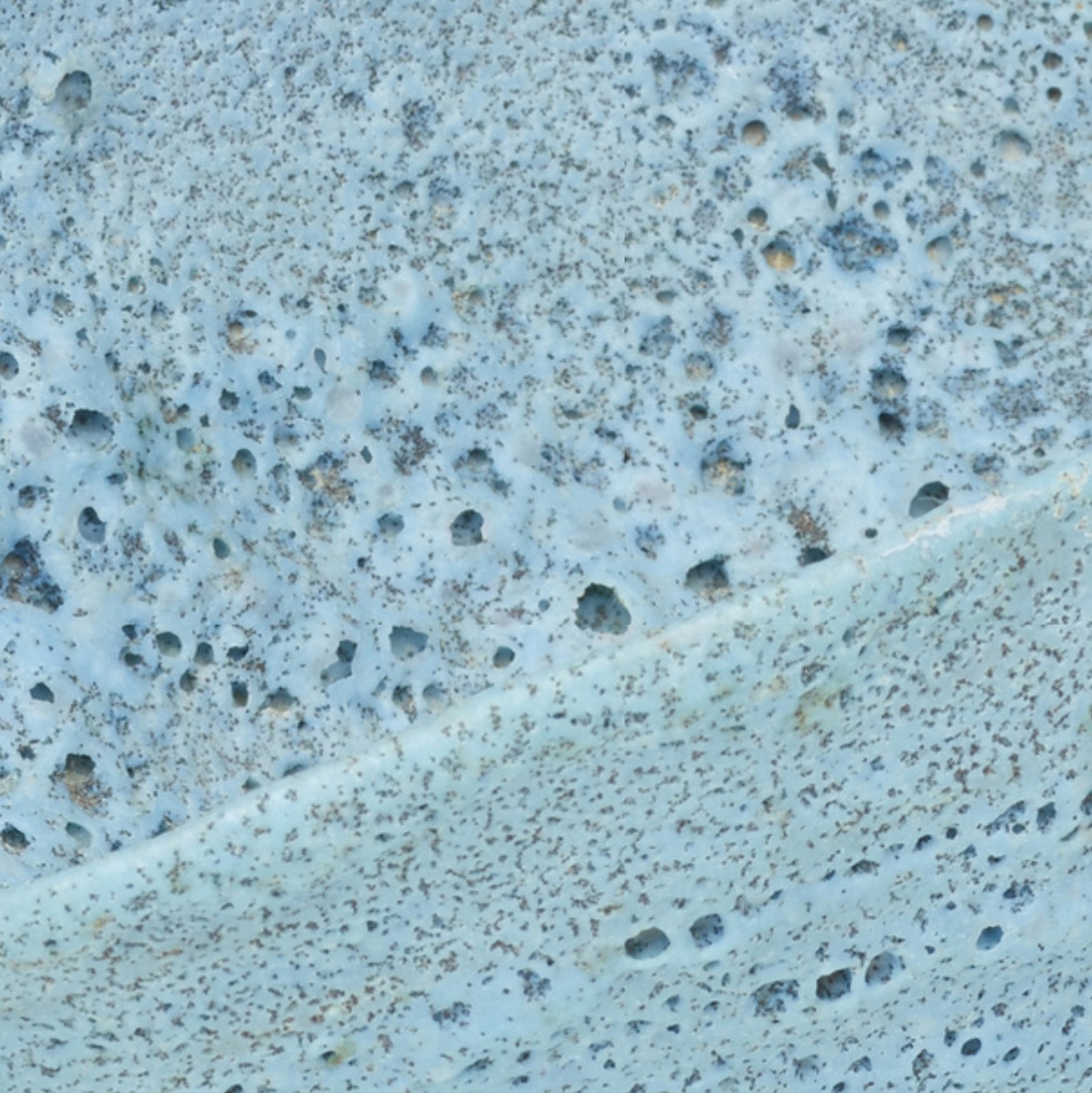

Gertrud and Otto Natzler

Bowl

c. 1965

Estimate: $1,000-$1,500

Result: $2,700

Lastly, the work of Gertrud and Otto Natzler. This tells us a lot about rising and falling prices and how narrow the ceramic market, or any market, often is. Their prices are a fraction of what they once were. Monumental works with spectacular glazes, at their peak sold for close to $300,000. America saw them as our Lucie Rie. (I would never have told that to Lucie.)

Gertrud and Otto Natzler

Bowl

Estimate: $1,800-$2,400

Result: $2,375

There were superficial similarities between Rie and the Natzlers. Both were Jewish and fled Austria in the late 1930’s, Rie to London and the Natzlers to Los Angeles. Their aesthetic was somewhat similar, reductive modern forms. Gertrud was a magical thrower. Yet the thin pure forms were a touch tight compared to Rie’s ease.

Gertrud felt that the minimalist elegance of her pots were often marred (and they were) by the histrionic, overly theatrical glazes that Otto concocted. But when her throwing merged with Otto’s more restrained glazes such as this Pale Blue Cup (Lot 689) achieved a sublime harmony.

Gertrud and Otto Natzler

Tall Coupe

1957

Estimate: $3,000-$4,000

Result: $3,000

The early six figure prices (not for these which are modestly scaled by their big masterpieces) were the result of only three hyper-competitive collectors. This is a lesson about a narrow collector base. When the trio stopped acquiring within a few months of each other, the market went from top rung into free fall and has not recovered.

There is another example of this I would like to share. It has nothing to do with this auction but is a learning moment. Friends of ours in Los Angeles had come into a lot of tax-free money and began to buy Victorian and Edwardian British art pottery: Martin Brothers, William de Morgan, Doulton’s Lambeth ware and others, eventually amassing the most important private collection of that genre (outside Gilbert and George).

With money no issue, they would arrive in London for the sales at Sotheby’s and Christies, take their places in the front row of chairs brandishing their feared, hard-working paddles, and never lost a piece they wanted no matter how outrageous the price might be.

A couple of years into collecting, a friend asked them if they knew who their biggest competitor was? “It is yourselves,” he pointed out. Once sellers realized their obsessive acquiring, they would place shills in the audience. After the legitimate buyers had dropped out, the shills kept bidding and pushing the price of major works higher and higher. Ordinarily this is risky game but not in this case.

Now aware of this game impact, they arrived for the next sale, took their usual front row seats in the room. The auctioneer banged the gavel to begin the sale and at that moment the pair stood up and left, leaving sellers pale faced and confused. Prices dropped by more than half. And sellers lost money. And some collectors paid too much. The auction is “buyer beware” territory.

You can learn about these artists here on the Cfile.Org site as well as writings about earlier auctions.

Now to the more contemporary artists in Part 2.

Garth Clark.

Add your valued opinion to this post.