OXFORD––This major new commission, at Modern Art Oxford, Oxford, by Mariana Castillo Deball (b. 1975 in Mexico City, lives and works in Berlin) fundamentally questions methods of knowledge formation in Western museum collections. Featuring an expansive aerial installation, archival photographs and repurposed museum display cases, the exhibition uncovers hidden stories and individuals, with a particular focus on artefacts and archives held in the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford and the Smithsonian Museum National Collections in Washington D.C.

For the exhibition Deball has created a dynamic suspended installation of ceramics and textiles. These hand-made objects are a demonstration of the artist’s observations on the early stages of ethnographic work when, as Deball states, “there was no difference between making and knowing something”. The ceramic pieces are made out of red stoneware and painted using techniques and designs common to the Zuni, a Native American Pueblo people native to the Zuni River valley.

The vessels are perforated with a ‘kill hole’, a gesture that was used by different cultures to eliminate the utilitarian value of an object. The artist uses these ‘kill hole’ perforations to connect the ceramics with ropes looping across the large gallery. These share the space with swathes of handmade textiles reaching eight meters in length. The fabric was produced in the state of Michoacan in Mexico by the collective Ukata, and are woven with a backstrap loom, and dyed with an ikat pattern.

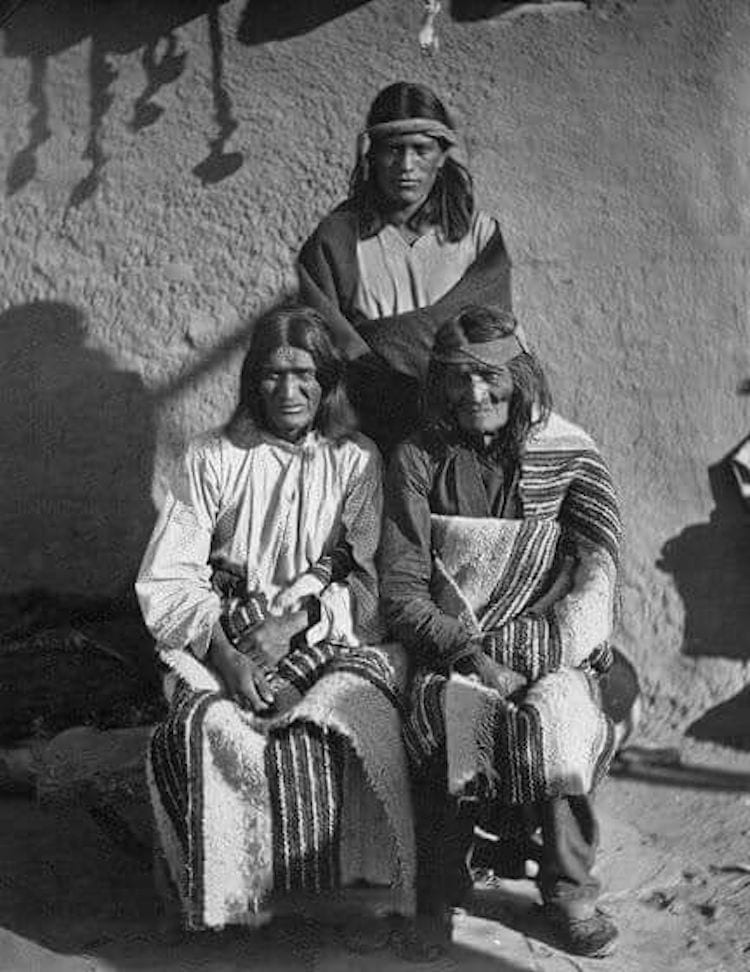

Through the exhibition Deball traces the lives of three researchers and makers: Zuni lhamana We’wha (1849–1896), her anthropological collaborator Matilda Coxe Stevenson (1849 -1915), and Elsie Colsell McDougall (1879–1961). We’wha had a particular position in society as an lhamana: male-bodied people who take on the social and ceremonial roles usually performed by women in their culture. We’wha had exceptional skills in weaving and pottery, and in 1886 she was part of the Zuni delegation to Washington D.C. hosted by Matilda Coxe Stevenson. We’wha produced objects on site, the process of fabrication on the ambiguous threshold of being both original artefacts and reproductions, which are part of the Smithsonian collection.

Matilda Coxe Stevenson travelled to the U.S. Southwest in the 1880s. She was interested in rituals and ceremonies, but also in the activities of daily life such as manufacturing adobe bricks, playing games, and collecting water. She documents these actions with her camera assembling series. She is a controversial figure among the Zuni people because the documentation of their rituals is forbidden. Stevenson’s early publications on the Zuni people were later eclipsed by contemporary anthropologist Frank Hamilton Cushing, who also blurred the lines “between knowing and making” as he made replicas of Zuni artifacts, which he described as re-enactments of indigenous technology or experimental reproductions.

The smaller galleries at Modern Art Oxford feature reproduced photographs documenting the fieldwork of explorer Elsie Colsell McDougall (1879–1961), who spent her life studying Mayan textile culture in Guatemala and Mexico, and Makereti (1873-1930), who was a highly successful tour guide in New Zealand, escorting visitors through the geyser valley of Whakerewarewa near Rotorua. She became a widely known ambassador and interpreter for Maori culture in the late Victorian period. These materials are displayed in 19th century museum cases loaned from the Natural History Museum in Oxford. One of the cases is empty and, through an audio piece, Deball reflects on the responsibilities and challenges of material culture as a contemporary artist.

Between making and knowing something is Deball’s first UK solo exhibition since 2013. For her, extensive research is essential to creating new ideas for an exhibition as her practice mediates between science, archaeology, and the visual arts, exploring the way these disciplines describe the world. Her work highlights collaborations and the exchange of knowledge as a transformative process for everyone involved, which she realises by experimenting with modes of reproduction. As she explains “recreating an object makes one understand and read the object in a different way”. Deball’s exhibition at Modern Art Oxford acknowledges how stories are performed and retained in museums, and makes visible lesser-known practitioners and makers, whose histories have remained too long obscured.

This exhibition is supported by the Mexican Embassy and Mexican Agency for International Development Cooperation (AMEXCID).

Learn more about Deball in Cfile.

Text and Images courtesy of Modern Art Oxford, Oxford. Photos by Ben Westoby.

Add your valued opinion to this post.