NEW YORK — Artist Christopher Russell was interviewed by Janet Abrams at the Daum Museum, MO on March 16 this year. His exhibition After the Golden Age was on display until May 29. Many of the works from this exhibition are now at the Julie Saul Gallery, in a two-person exhibit, Christopher Russell and Zachari Logan: Hypernatural (New York, through August 12, 2016).

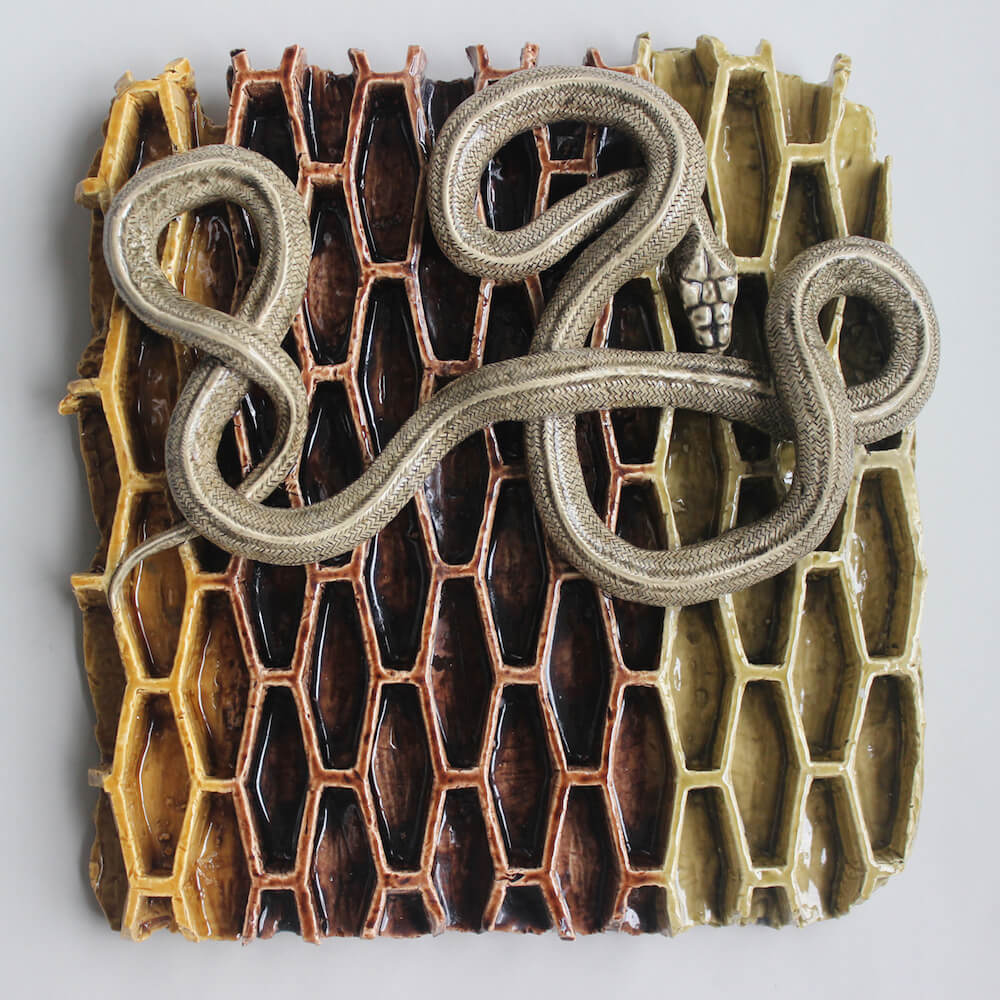

Above image: Christopher Russell, Design #7, 2015, glazed white terracotta, 15 1/2 x 15 1/2 x 4 inches

JA: What is the key metaphor of this body of work? What are you saying?

CR: The piece called After the Golden Age came out of a trip I made to Paris around 2010. Looking around at how beautiful it was, and its rich history, at some point I realized there was a huge sadness to the whole thing. Its glory is its past. We were at the Place Vendome, where there are obelisks that Napoleon put up to glorify one of his arrivals. Everywhere around Paris you see these symbols of power, achievement, ambition, success. Inevitably they become symbols of the loss of that power, of past empires. At Olympia, the columns for the enormous temple to Zeus are now toppled over: discs that were once piled on top of each other are now sliding like dominoes. This was the peak of civilization at the time, but here they are, literally in a pile on the ground.

Looking back at these different eras, I began thinking about the kinds of objects you see in the back rooms of museums, objects owned by the wealthy that were, in their time, emblems of status and luxury. The Jeff Koons or the Damien Hirsts of their moment. I like the idea of this back room for objects we don’t really need any more.

Christopher Russell, After the Golden Age, 2001, glazed earthenware, variable dimensions. Click to see a larger image.

JA: Is that why the Roman sandal foot and the bust in After the Golden Age are facing inward? This piece isn’t so much a display as it’s Open Storage, like the new ceramics galleries at the V&A.

CR: Not Open Storage. Just: Storage.

JA: I’m curious about the way the pieces are set up on this plinth.

CR: Julie [Saul] and I designed it. I wanted it to be furniture-like. Julie had the idea of making it open underneath, so you could see through it.

JA: It’s half way between a table and a gurney.

CR: This piece is like a kind of cemetery. Some of the objects are pure pastiche; some are vague copies; some I completely made up. At Chatsworth they have this big stone foot. Any self-regarding guy in the 1700s would have a big foot in the back garden. This is my version of a large bronze foot, which is all that remains of a full bronze figure of Louis XIV, that was cut down during the French Revolution and made into bullets, armor, to fight against him with. And here’s a chalice that probably never existed, which I made from a charcoal drawing on the Metropolitan Museum’s website — though my guess is the design was never carried out.

JA: So let’s step back. Are we in a “Golden Age”? Are we leaving a Golden Age? Is this all a comment on America? You’ve got a lot of birds of prey in here, which look like eagles…

CR: I wasn’t thinking of things politically. This is just about being a human. Somewhere I came across this line: “Every portrait essentially becomes an elegy.” The minute it’s done, it becomes a portrait of something you were in the past and never will be again. Everything we make eventually becomes a memento mori.

JA: The piece called Tooth and Claw presumably alludes to “Nature Red in Tooth and Claw.”

CR: A phrase that Darwin borrowed from Yeats or Wordsworth.

JA: Though I can’t help seeing Ratatouille, the movie, when I look at it: all those lovely rats!

CR: When I showed this piece, a woman asked me: “Is this about the 1%?” I don’t necessarily believe that theory — that there’s a big guy on the top guzzling away at this food chain. To me it’s partly a 3D version of a painted still life.

JA: …minus the colors.

CR: Which makes it ghostly. Most Still Lives have an element that indicates it’s in decay: a skull in the corner, or snails, caterpillars going around. You’re catching it at its peak, and it’s about to fall over. Still Life pieces already refer to death. I decided to name these pieces “Arrangements” as in “Funeral Arrangements.”

There’s a whole structure inside them — rings of clay — so they’re surprisingly strong. I work almost exclusively in low-fire white terracotta, electric fired, though I made these flowers — sunflowers, mixed flowers, and roses — out of porcelain.

JA: Tell me about the glazes, which are either a honey color or a grey.

CR: They’re Cone 04 glazes. I’d been working almost entirely in the honey glaze because I love the way it looks: it reminds me of the old lead glazes, but without the toxicity. It’s a very simple burnt umber oxide glaze. When I returned from that Paris experience, around 2010, I thought of making a whole group of triumphal, heroic objects in yellow, but at some point I decided: these pieces should be grey. That’s the right color to get the emotion I want for them. The base is my version of the Worthington glaze: the original is 55% Gerstley Borate, 30% or so EPK, and 15% Silica. Over the years, I’ve developed a number of oxide additions that give me the different colors. This particular gray must be manganese, cobalt and burnt umber, maybe some copper in there.

JA: You’ve played around with the recipe?

I’ve adjusted it; it’s very specific to this clay body. At the same time I was looking at Piranesi, and at images of these old objects in the form of etchings and engravings, done in this grey, printer-like way. I think my line making is very drawing-like.There’s a similarity between printmaking and ceramics. They’re both transformative processes. You’re making something and you don’t know what it’s going to look like. You’re constantly imagining what it’s going to be. You make the piece, put it in the kiln, then it comes out and you go, “Oh! There’s the piece!” I always have this funny thing when I fire a kiln. I go home, and next morning on my way back to the studio — this is so weird — it’s as if the piece has been delivered to me by Fedex. I made the piece, but I’ve never seen it before!

JA: You’re lucky, if you look inside the kiln and it’s actually in one piece.

CR: Yes, there’s that, which often doesn’t happen. I was also looking at Piranesi, and a lot of the documentation of this kind of work was in the form of etchings, engravings done in this grey printer-like way. I think my line making is very drawing-like.

JA: I actually can’t quite tell what you’re saying with After The Golden Age as much as I think I can with To Each His Own, where the birds are savaging some kind of epaulette or military honor, and there are all these gems but also a raw voraciousness. That piece is less a comment of an elegiac kind. To gauge by the number of obelisks and the finesse of everything in After the Golden Age, there’s still a celebratory component as opposed to a warning of the inevitability of collapse of some triumphal regime, or whatever it is.

CR: Absolutely. I agree.

JA: So would you say that was a success or a failure of this piece?

CR: There is a kind of object-fetish about it. I’ve said this in the past: to some degree, the reason I make things is because I want to own them. For instance, one of the pieces in After the Golden Age is based on an object covered with gems, silver and gold, called the Kniphausen Hawk, which was owned by the Earl of Devonshire and is on display at Chatsworth House in England. It’s a totally over-the-top luxe object. The weirdest thing is that the head comes off and it’s a decanter! So part of my motivation is: “I’m going to make it, and then I’ll have one!” At the same time there’s this idea that these objects are ridiculous, vain. The way I’ve set them up means that they’re not are shown off at their best. I see them as a bunch of stuff put into a corner. That’s intentional. I’m not making a political comment about the present day. To me it’s much more about the way life is, than about this particular moment. These are sad pieces. They’re about sadness. They’re about the way things fade; the violence that almost always underlies status; the kind of greed that’s futile. Ultimately, it all fades.

JA: Let’s change the subject! Let’s talk about the botanical drawing classes you did in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

CR: I loved scientific illustration and I took a series of botanical illustration courses at the New York Botanical Gardens. I was amazed that people could actually do that. I was looking at very detailed and intricate drawings of beehives in a fascinating book called Beehive As Metaphor, and said to myself “I wonder if I can make that?” The beehive can either be seen as this Perfect Brotherhood working together, or as Automatons that just work and work and work until they die. People are sometimes called “drones.” I began thinking about all those meanings. Very often, the first idea is just: “Can I do that?” The flowers are all pretty accurately drawn.

JA: Do you draw each flower and then make it in clay? Or do you by now have a library of drawings of each species you pull from?

CR: Frankly now I just use the Internet: I look for scientific illustrations, or just drawings from gardening catalogs. I have some books as well. Then I start making them. I really don’t draw them very much. Sometimes I make press moulds that allow me to press out different parts of flowers, and produce different arrangements of the Easter Lily petals, the hydrangeas.

JA: The dripping of the glaze makes it look like honey. You want to lick it. But it’s not realistic. It’s the giveaway that the piece is made of clay.

CR: It’s also part of the process. You don’t just see the detail; the glaze draws it for you. Then you get the dripping. It gives the whole thing an abstract quality.

JA: That effect doesn’t happen so much with the grey glaze. It’s what gives the honey-colored pieces an elegiac quality: they’ve got this glaze that looks…contaminated. Something’s wrong.

CR: Like it’s been left out some place.

JA: And it’s dripping… What’s going on with this obsessive massing of gems and snails in the piece called The Apotheosis of the Slow?

CR: They refer to coquillages — covering things in shell. There’s a piece in the Everson Museum that was a famous technical triumph of ceramics: The Apotheosis of the Toiler, made by Adelaide Robineau in 1910. It has a design of a scarab rolling its dung ball up to the top, so it’s also known as the “Scarab Vase” and the “Thousand Hour Vase,” in honor of the time it took to make. It’s my ceramic joke that my piece is called The Apotheosis of the Slow. I was thinking about the idea of nature engulfing this classical ceramic object.

JA: I suppose because I didn’t have lunch, I keep looking at them and seeing caramel popcorn! I want to grab a chunk and take a mouthful.

CR: A few people have said things like that. With this color, there’s definitely a caramel candy, burnt sugar quality.

JA: But it isn’t the kind of barnacling that would happen if these pieces were just left by the seashore. It doesn’t have that natural accretion over time: it’s too perfect, too purposeful, too ‘all at once’.

CR: To me, they’re not barnacles. I didn’t make them ‘mossy’ — I just wanted purely this surface of snails: as if snails came up and engulfed these busts, like an army. I’d been invited to work in a pottery at a Scottish design company, in the most beautiful place I’d ever been, in a house with lots of snails in the yard. I wanted to make something completely absorbed by nature. The Apotheosis of the Slow talks about time — including the ridiculous amount of work that went into making it. Underneath are not-completely-finished busts, which is how you make it look like a bust when it’s covered in snails.

JA Are you attaching the snails to each other, or is the glaze doing that?

CR: It’s all slipped together, then bisqued, then glazed. The snails were very time consuming, because I had to do three coats: some are just the yellow glaze, some are just brown, and others are half brown, half yellow. Again, it’s my version of the Worthington glaze.

JA: What are you thinking when you’re making these pieces?

CR: “I’ve got to get these done for the day of the show!” I can’t believe it took so long.

Christopher Russell, Design #2, 2015, glazed white terracotta, 15 1/2 x 15 1/2 x 4 inches. Click to see a larger image.

Christopher Russell, Design #3, 2015, glazed white terracotta, 15 1/2 x 15 1/2 x 4 inches. Click to see a larger image.

JA: Tell me about To Each His Own:

CR: I wanted to make an organic looking object, covered in gems, like a gnome’s dwelling. I was reading about the Age of the Enlightenment, and came upon the Order of the Templar Cross, to which almost every Royal man in Europe belonged. Its motto was “To Each His Own,” implying there was going to be peace among all these royal people. “What’s ours is ours, and leave everybody else alone.” But if you get your hands on it, it’s suddenly yours. This completely invented object in To Each His Own [the epaulette-like thing the birds are attacking] is a prize of some kind.

JA: The snakes are new. I love these. This is a change in your work. They’re a funny combination of what you’ve been doing based on the botanical drawings, with some sort of Mid-Century Modern thing — that honeycomb Scandinavian-ish pattern, for example.

CR: I’d been dealing with the issue of the snails’ antennae — so small they’re impossible to handle — so I was looking for an interesting creature that isn’t covered with all kinds of things sticking out of it. A snake! I thought: that’s a pretty simple shape. But actually they’re tricky to produce. A lot of them ended up with firing cracks. I’d make the under piece, then I’d make the snake separately, hollowing it out, attaching it to the back piece, and connecting all the sections I’d cut off. Getting the shrinkage right between the two was difficult. It took a day each to put the patterns on the snakes.

Christopher Russell, Design #10, 2015, glazed white terracotta, 16 1/2 x 4 inches. Click to see a larger image.

JA: Do you think of these pieces as a set?

CR: I wanted to make a series of pieces for the Daum Museum show, and I wanted them to be in a line, almost like Arabic writing, a script going down the wall. I very consciously decided on the variety of snake shapes: a spread-out one, a coiled one, etc. Technically, this was a very different project for me. They’re called “Designs” as in “making designs on you” — that slightly evil quality — but also a celebration of different design techniques such as medieval carving, Arabic stone grille work, Chinese textile, Rococo stuff. My wife and I went to LA, and I decided our job was to find the next material. Gina went into the bathroom at the Neutra house and called out “I’ve got it!” It was actually a pattern on flat tiles in there, but I think the honeycomb shape is beautiful.

Janet Abrams is an artist and writer based in Santa Fe. Her ceramic installation, In The Unlikely Event — the world’s 30 busiest International Airports hand built in terracotta — is on exhibit at Form & Concept , Santa Fe, through August 22.

Do you love or loathe these works of contemporary ceramic art? Let us know in the comments.

Add your valued opinion to this post.