The exhibition Bouke de Vries: Fragments has opened at the Château de Nyon (Nyon, Switzerland, November 28, 2014 – April 12, 2015) which houses three museums. Bouke de Vries’ works are being shown in the Musée Historique et des Porcelaines (founded in 1888). It is a remarkable exhibition in a remarkable setting. Created as a fort, the first reference to the building is dated 1272 and it went through several restorations over the centuries.

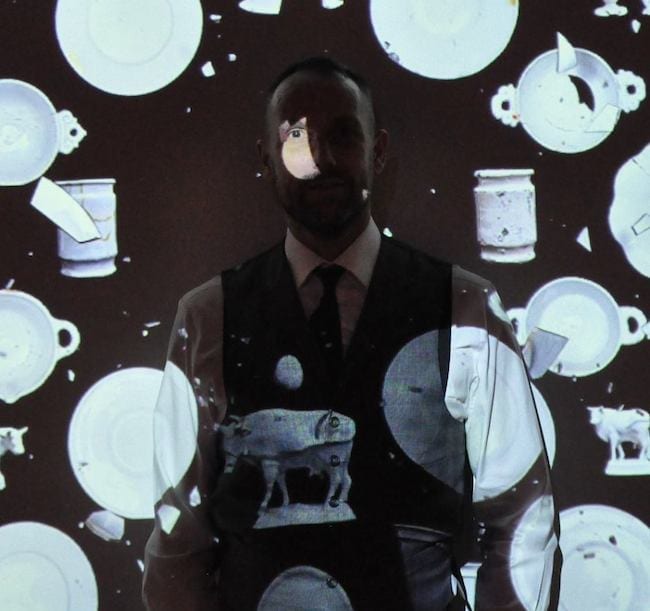

Above image: Bouke de Vries standing in front of his projection piece The Wall, 2014, at the Château de Nyon exhibition opening.

Bouke de Vries, Marge Simpson as Guan Yin Goddess of Compassion, 2014

In this context the artist time travels to the 21st century. It’s exemplified by a Guan Yin Goddess of Compassion transformed into Marge Simpson with her children. That work is both at home due to its use of antiquity, and due to the artist’s interventions, more unsettling than it would be in, say, a white cube. It is the perfect storm. This contradiction provides a lively tension to his animation of the past. Recently, de Vries was interviewed by Tim Blanks for a profile in the T Magazine, New York Times. Here is an excerpt:

“The 53-year-old Dutch artist was originally drawn to restoring ceramics as “a noble profession, saving the nation’s heritage.” De Vries originally studied textiles at the Design Academy in Eindhoven. After completing his postgrad work at the Central School of Arts & Crafts in London (before it became Central Saint Martins), he assisted Zandra Rhodes, made hats for Stephen Jones and worked with John Galliano on his first two collections, but all that left him dissatisfied. So when his partner, Miles Chapman, asked him what he really wanted to do with his life, he sought out a college course specializing in ceramics restoration.

“Starting out, de Vries did work for institutions like the National Trust and Christie’s, artists like Grayson Perry and Gavin Turk and the estates of iconic ceramists Lucie Rie and Hans Coper. Five years ago, he got itchy fingers, so following the classic budding novelist’s dictum — write what you know — he decided to do something using broken ceramics.

“All over the house he shares in West London with Chapman and Sonny, a hyperactive Manchester terrier, there is impressive evidence of his genius at repurposing and elevating fragments of the past. On one wall of the living room, there is one of his updated earthenware versions of the displays that were popular in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, when blue-and-white Chinese porcelain was a status symbol. For his, de Vries chose only white pieces, “all very much of a domestic nature, for use on a daily basis and thrown in rubbish pits once broken.” On the opposite wall, he has made a map of Holland using fragments from the same excavation site. “The idea is that clay from Holland made the objects,” de Vries explains. “They were broken and returned to the soil of Holland, then excavated and used by me to create the Netherlands again, thus completing the circle.”

“You could almost see the peculiar poetry of these pieces as something spiritual, a kind of rebirth. De Vries isn’t averse to the idea. It’s obvious when he reconstitutes a porcelain Christ, then attaches a butterfly to it. ‘In Dutch still lifes, the butterfly is a symbol of resurrection,’ he says.

“He never buys something just to break it. One of his latest works is a collection of Royal Worcester porcelain — teapot, coffeepot, milk jug, ewer — the shattered pieces of each contained within a glass simulacrum of the original shape. ‘I always let the object dictate.’ De Vries and Perry occasionally collaborate. Perry will smash a piece, and then de Vries will put it back together.Sometimes they use gold joints, which makes for a beautiful piece. In fact, they’ve just created a work like this for Perry’s show currently at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

“Those objects have now directed him to the Château de Nyon, just north of Geneva, where at the end of the month, de Vries is opening an exhibition of his work. The astounding centerpiece of the [Château de Nyon] exhibition, originally commissioned by the Holburne Museum in Bath, is “War and Pieces,” an installation which refers back to the sugar sculptures that once decorated the dinner table of the high and mighty in the 17th and 18th centuries. The more sugar used, the greater the host’s wealth. Eventually, sugar was replaced by porcelain, to the same self-aggrandizing end. ‘Battles were very much planned in the 18th century,” de Vries takes up the tale, “and before a big battle, there were always banquets and balls. So I thought, ‘Let’s have a battle on the table between the classic and the contemporary, between sugar and porcelain and plastic.’ ‘ On the “War and Pieces” table — surrounding place settings, which de Vries has also created — pristine forms based on 18th-century figurines stand next to plastic robots from flea markets and an atomic mushroom cloud, casting its decisive pall over the entire scenario. The piece is ironic, satirical, political, akin to something the Chapman Brothers might do, but it is also extremely beautiful, the pure white ceramic of the cloud looming like a giant flower. ‘I was drawn to the idea of something so ugly being so beautiful as well,’ he adds.”

CFile has previously published a review of the artist’s exhibition Memories. A studio tour can be seen here.

Garth Clark is the Chief Editor of CFile.

Any thoughts about this post? Share yours in the comment box below.

Bouke de Vries, Deconstructed Moon Jar with Insects, 2014

Bouke de Vries, Deconstructed Guan Yin.

Bouke de Vries, Portrait of the Artist 1 (Reconstructed Dutch Boy), 2009

Bouke de Vries, Cloud Blue and White 2, 2014

Bouke de Vries, War and Pieces, installation view. photographed while at the Holburne Museum.

Installation views of Bouke de Vries: Fragments at Château de Nyon.

The Château de Nyon.

I like that his work grew organically as an unintended consequence of his path, and not some art school BS . . . that the supportive armatures of the exploded pieces are handled elegantly speaks well of his art . . .