The Following is a review by Eric Zetterquist of Human: The Art of Beth Cavener.

It is with trepidation that I invite a new artbook into my already heaving library. It can’t just be beautiful and informative; It needs to be indispensable. “Human: The Art of Beth Cavener” is all of that. Published by Fresco Books, whose recent efforts include the joyful “Menage Beato” and the fabulous “Dark Light: The Ceramics of Christine Nofchissey McHorse”, this large, sumptuous, and exquisitely printed catalogue raisonne is our only opportunity to see and understand all of Beth Cavener’s haunting sculpture. Her gallery exhibitions are paced years apart, and her limited output over the last 20 years can only be seen in geographically scattered museum collections and a handful of jealously guarded private collections. So, grab this opportunity, as the book grabs our rapt attention from first sight.

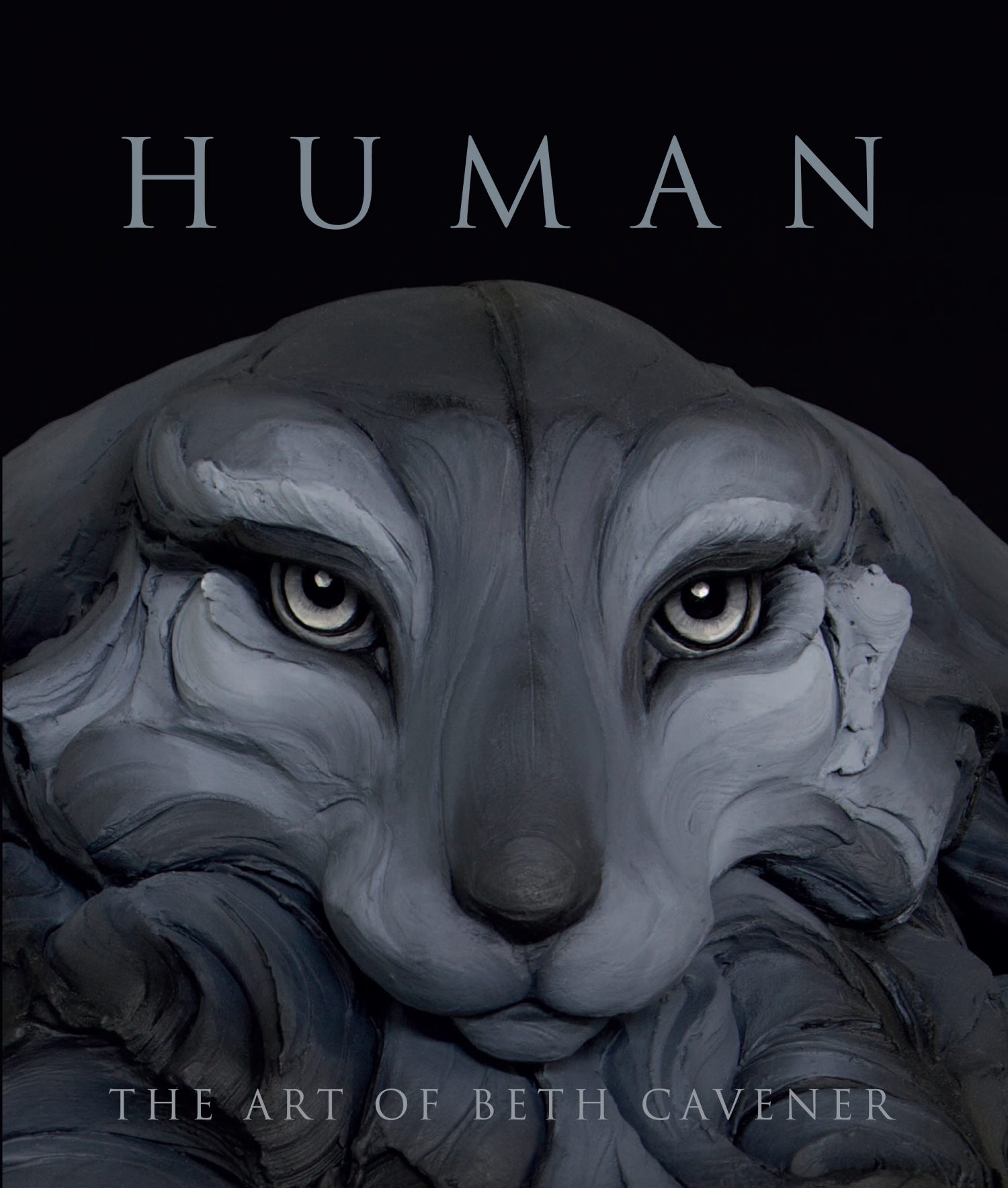

In a single stroke, the cover reveals the ironic genius of its subject; The title “HUMAN” is emblazoned over the face of a rabbit, staring insolently back at the viewer, as if daring them to open it. Beth Cavener’s work taunts viewers with raw human emotions personified by animals. But ultimately, it is the viewer’s own psychological baggage that hooks them into the work, and makes it meaningful to everyone on their own terms. (As any psychologist will attest, it is not the dream itself, but how the dreamer interprets it, that is meaningful.). Once you can tear your eyes away from the sculpture, reading the titles of each work further reveals the core of the pathos being expressed. They include sexual identity, co-dependence, and feelings of entrapment.

As I wrote in a recent exhibition review of her work, “…this is no petting zoo, but a natural history museum of adult disappointments”

It is a temptation to go right for the pictures when one opens an artbook, but with Cavener’s work, one needs a little guidance and insight to better understand the visuals. Garth Clark’s characteristically thoughtful and enlightening introduction, “Avatars + Arbiters”, does this well. He liberally (and wisely) quotes the artist, who is an eloquent commentator of her own work, weaving in childhood memories and adult revelations to shed a light on her motivations in creating these beguiling and disturbing creatures.

One of the most telling passages describes how Cavener used animals to explain human behavior as a child.

“She coped by assigning animal identities to her more difficult classmates. It was a way of taking the sting out of their cruelties. That person behaved that way because that was how their assigned animal behaved. It was their inherited nature. In accepting that, she depersonalized their behavior (blamed the animal), and made their unkindness endurable.”

He continues by explaining how she coopted this devise in her adult art, melding animal form with human thought, creating a perpetually fascinating genre.

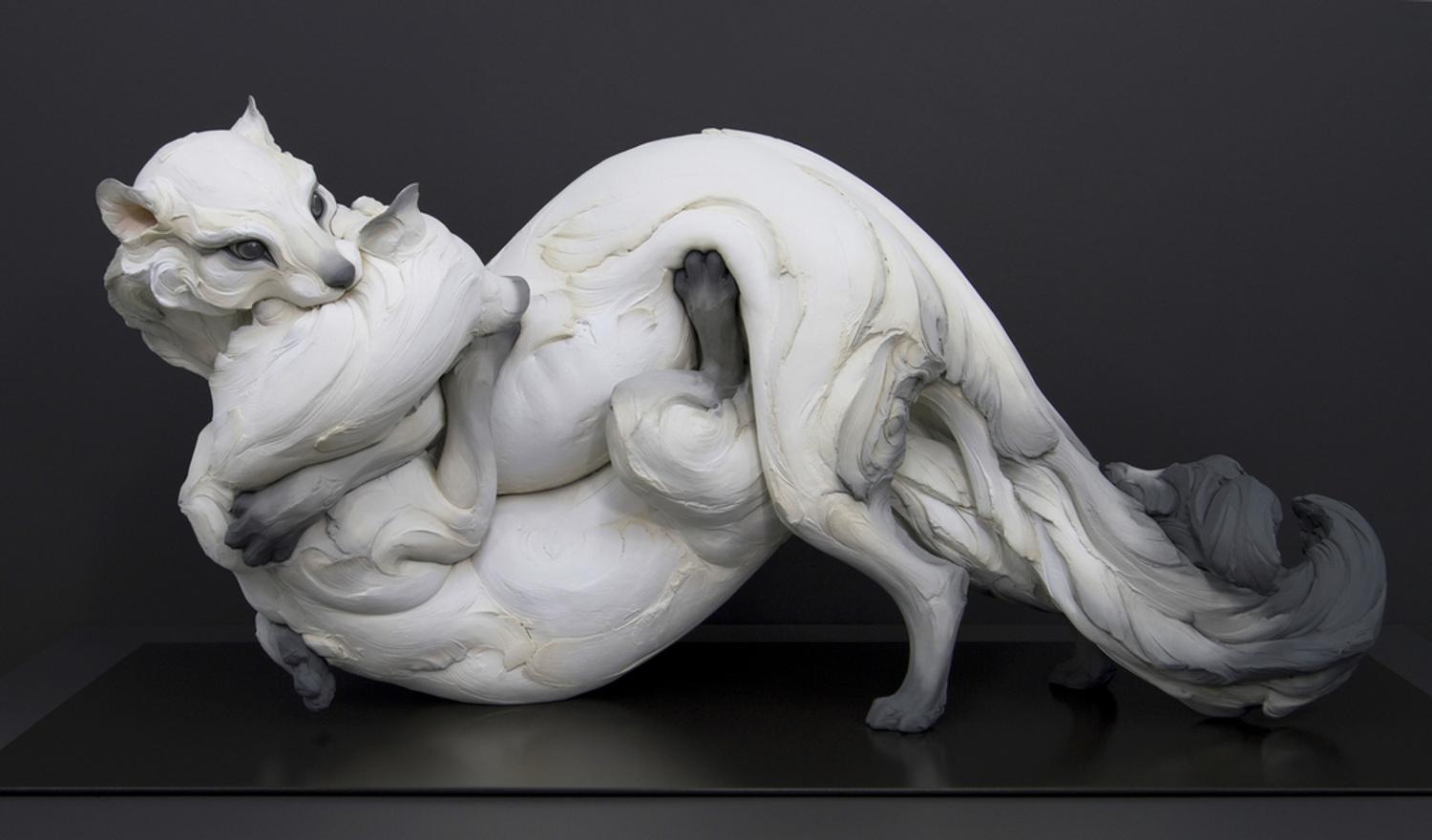

As one of the world’s foremost ceramic experts, Clark is the first to point out that although Cavener uses ceramic as a medium for her sculpture, it is not about ceramics. It is simply the most expedient medium for her to convey the sculptural sensuality (fleshiness) of her subjects, and allows for an infinite color palette, which she uses to evocative effect.

“Cavener carries no ceramic baggage. There is no footnoting from the medium’s history. Her figures have no connection to figurative or animal figure in ceramics past: not Staffordshire figurines, European Court Porcelains, Tang women, Inca warriors, or anything else. Her art is untethered, contemporary invention.”

Using two of her masterworks to offer insight into the total oeuvre presented in the book, we get more insight into the artist herself, which prepares us (as much as possible!) for the visual pleasures and psychodrama that follows.

One cannot blithely flip through this book. Each of these animals in the 195 pages of full-and-double-page photographs demands your attention, and then complicity, in what they are expressing. Bound, trussed, hung, perched, stuffed, propped up, and splayed, these animals take us through a rollercoaster of emotions. We feel RAGE! GUILT! SADDNESS! RESENTMENT! RESIGNATION. Is there HOPE?

Yes, however the hope does NOT come from the solution of the problems, but rather in their acknowledgement, and acceptance. Cavener’s animals are unflinchingly aware of their predicament, and present themselves without shame. They challenge us with their eyes, and we are appalled and impressed. I am reminded of the photography of Dorthea Lange whose subjects don’t smile pretty for the camera; They sear holes through it with their eyes, forcing us to break down our self-deceptions.

However singular Beth Cavener and her maladjusted menagerie are in today’s artworld, she is part of an historic tradition of animalia, reaching back to ancients. In his lucid and informative essay, Ezra Shales, first places her work in the context of 18th century Enlightenment philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau:

“…. There always remains the question of projection: Is savagery an entirely human quality? If so, one could argue that cruelty is what makes us humans distinct from the animals we hunt, assembling as prizes and pets. By identifying a ‘noble savage’, Enlightenment philosophes could abstract human tendencies in the most bizarre ways, fusing and transposing their own sexual suppressions and inhibitions so as to languish in alternating visions of ‘the primitive’ with contempt and fetishization.”

He then continues to explore her predecessors in 18th – 20th century visual arts who used animals to evoke human emotion or self-recognition. Looking at the work of Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Antoine-Louis Bayre, J.J. Grandville, Francois Boucher and even Japanese netsuke, he makes the point that, while yes, artists have used animalia as a device for human representation in the past, few have used it to such a “boldly carnal and unabashedly prurient” manner. (And, how could they? Cavener’s work is shocking enough in the 21st century….). Shales draws a particularly poignant comparison between Francois Bucher’s 1747 “Pence-t-il aux Raisins”, which insinuates goats and sheep into a pastural depiction of two amorous humans to amplify the sensuousness of their interaction. Of Cavener’s place in the animalia tradition, he concludes:

“…. It is astonishing to step back and realize that an animalier could be so relentlessly inventive and tempestuous in the twenty-first century, and the human imagination so vibrant and fertile to manufacture these credible nightmares and seductive fantasies.”

The final essay, by Lauren Amalia Redding, compares Beth Cavener to George Orwell and Orson Welles. In a (perhaps unavoidable) comparison between the characters of George Orwell’s masterpiece, “Animal Farm”, the author points to a common recognition of the futility of the animals’ existence, and resignation to their state of being.

“Whether muted or militaristic, Orwell and Cavener proves that ‘human nature’ sets a stage – a muddy farm for the former, a frigid landscape for the latter – upon which both animals and humans indistinguishably portray a recurring cast of characters.”

Freud looms large in Ms. Redding’s caparison between the work of Cavener and Orson Welles. In the gray area between id and superego, regulated by the ego, there is no right and wrong, just self-awareness and a desire steer away from destruction. Similarly, she asserts that Cavener’s animals are brutally self-aware, and present themselves without shame. The author engagingly compares the subtlety of expression of Cavener’s animals to Orwell’s cinematography style, which used extreme close-ups and subtleties of expression to heighten conveyance of emotion.

In the end, it is the universality of Cavener’s work that captivates us, and Redding encapsulates this phenomenon succinctly:

“Cavener’s animals are autobiographical: not just for Cavener, but for everyone who views them.”

Publishing a catalogue raisonne is an act of bravery. While the goal is to be useful and impressive, one might ask “What? Is that it, then?” What we learn from viewing the breathtaking totality of Cavener’s work over 26 years is that she has exhibited bravery in each and every piece. Gauntlet tossed.

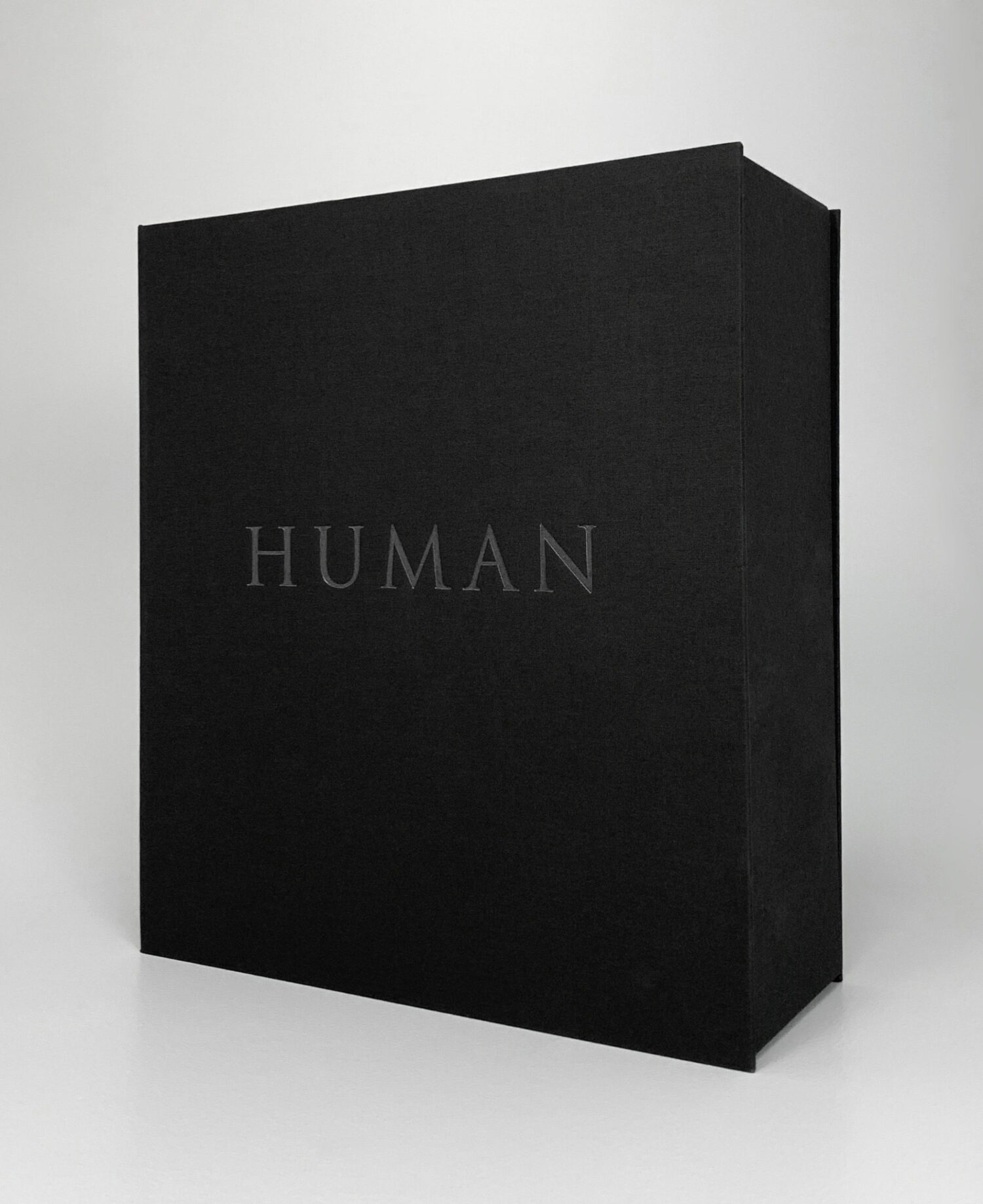

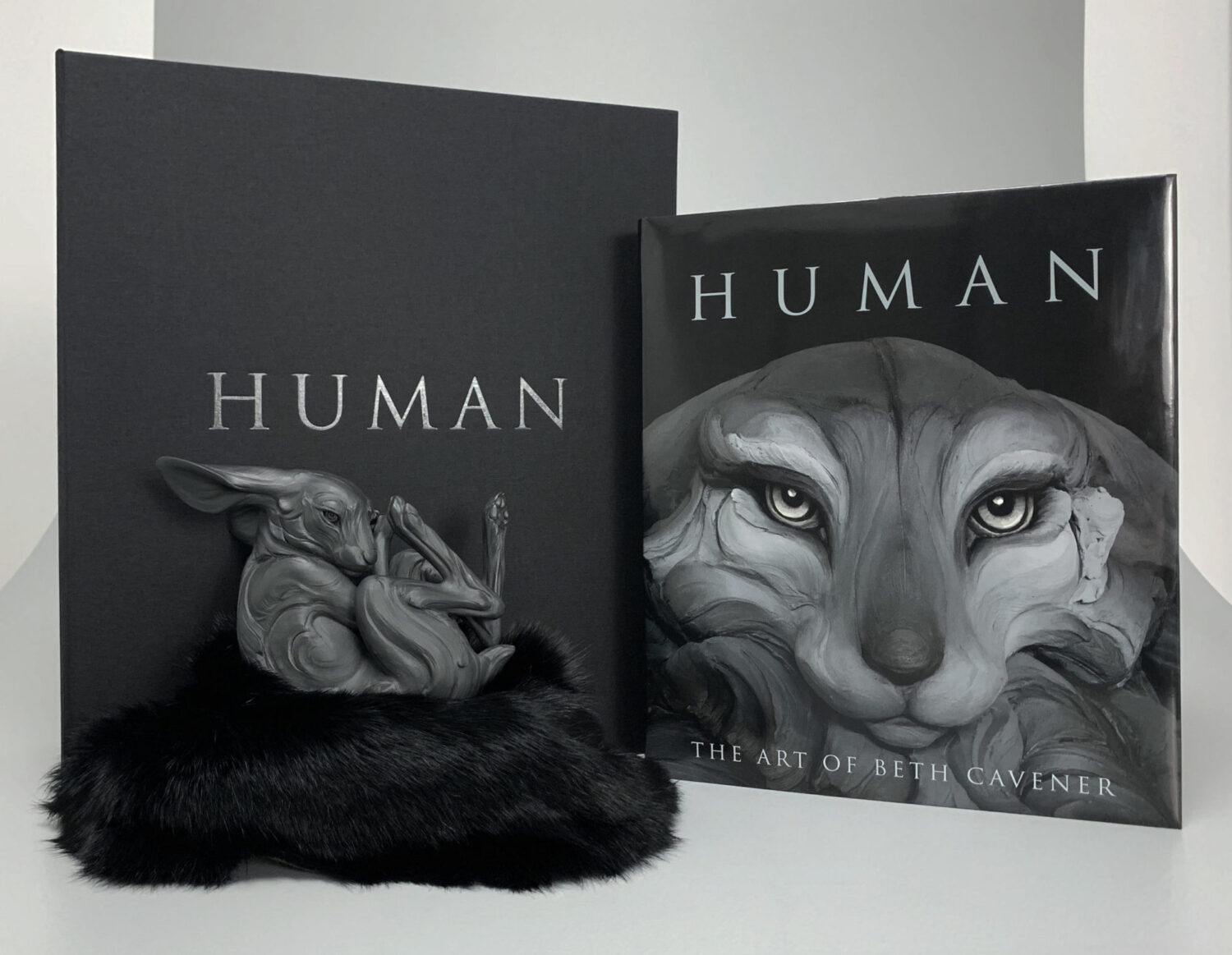

Artbooks are an artform. But like other artforms, they fail if execution is second rate. Exquisite visuals on unworthy paper and printing can create an unforgivable disconnect, distracting the viewer (holder) from the greater purpose of understanding the essence of the art inside. Everything about “Human”: the design, choice of paper, sensitive printing, superb binding and most importantly, the photography, is of the highest quality.

It is little wonder that in the short period since it has been published, “Human” has won two prestigious book awards. It won a first place award both in the Fine Art category from the Independent Press Award and the top honor, an IPPY Gold Medal, from the Independent Publishers Association.

vA Deluxe limited edition book, packaged in an exquisite custom clamshell box with a limited edition sculpture of a rabbit, is available through Jason Jacques Gallery in New York. Regular copies signed by the artist can be bought directly from Cavener.

Eric Zetterquist has ran Zetterquist Galleries out of New York city since 1992. He is also an artist with a keen interest in ceramics and photography.

Oh my oh my, ERic

The first time I saw Beth was at NCECA with a truck load of clay and thirty students on stage throwing her 50# at a time to her, She was using a 2X4 to beat the clay onto her armature in to the shape of herself/ her rabbit. In the two days of the conference her performance, heartbeat and heavy breathing were all we wanted to hear while we never took our eyes away. The other two performers on stage were not even there . Then she took a cut wire to it and cut the muzzle from the four ft long face to demonstrate how she hollows her sculptures out.

The next year I brought my daughter Ariel to campus. She had been in the Ceramics Lab many times, to wait on me, having work to catch up on But this year she was a little older, and might have been anxious waiting for me in my office, so I asked her if she wanted to watch a favorite movie of mine. “yeah!” She watched Beth sculpt at her peak of energy ( the tape from NCECA).

Ariel makes prehistoric animal sculptures now reflecting various stages in her life, in everyone’s life truly and only after grad school in Florida, a serendipity encounter with Beth, took her to Beth’s for a Summer internship. She was welcomed there and to return anytime for ever. Beth gave her a copy of her book.

Can you identify what my art is about ? You art is writing. I will go on a search o see your more of your art. I excerpted parts of this to share in Lesson 10 with my students. Their question will be: What makes a work Art?

Dear Karmien,

How lucky are your students (and daughter) to have a professor who challenges them so!

Here is my tiny answer to a colossal question; What makes art?

Soulfulness.

Even Geert Lap’s work, which might appear to be cold, hard minimalism, has incredibly soulful (sensual) surfaces.

Keep up your good work!

Eric