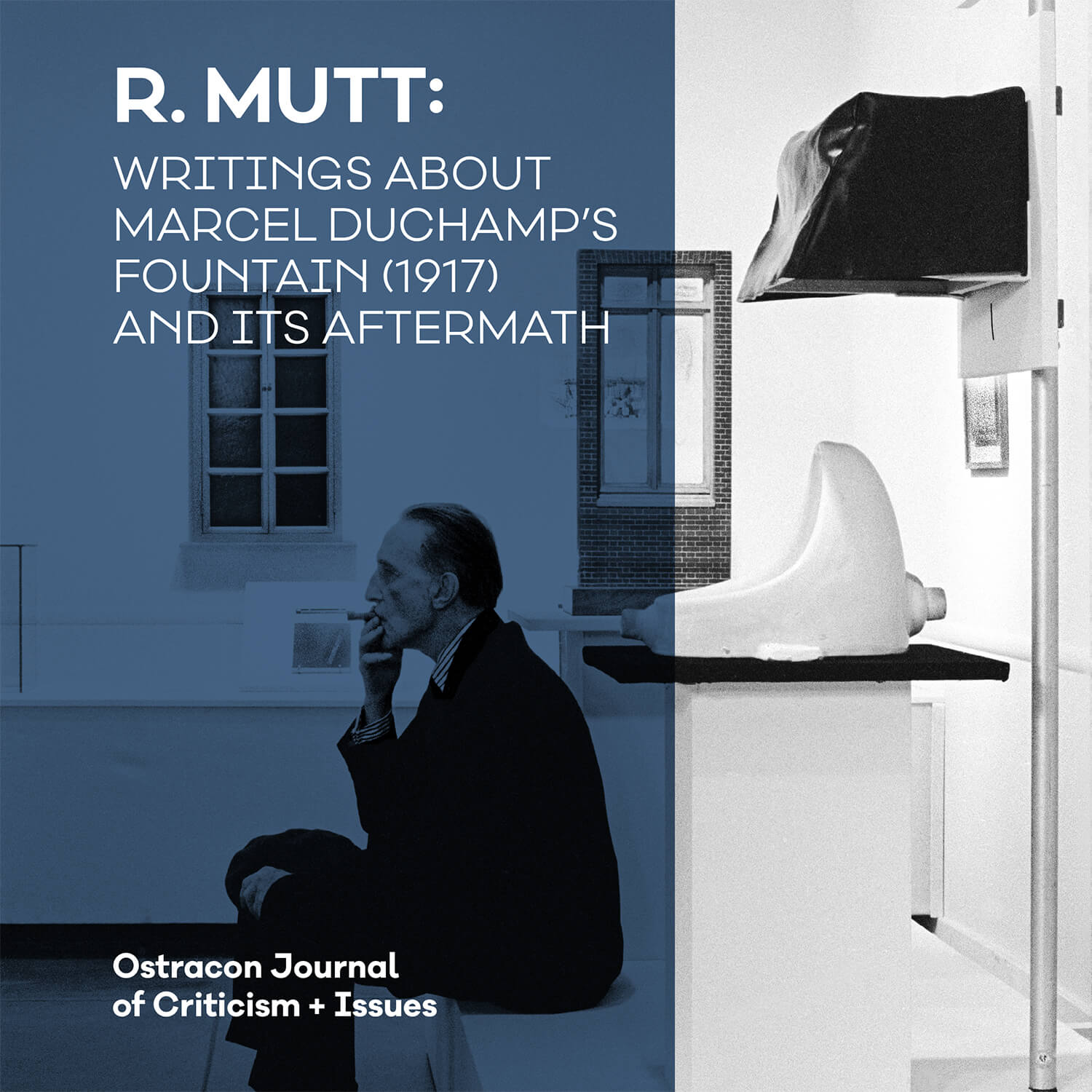

Ostracon 3 is LIVE! We are so proud to introduce the most comprehensive anthology of critical writing on Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917). This publication celebrates the 100th anniversary of the world’s #1 contemporary art object with essays by Francis M. Naumann, Ezra Shales, Dalia Judovitz and seven other scholars. Free for one week, then R.Mutt is only available to members of cfile.campus. Check out this beauty while it’s free!

The following essay is Garth Clark’s the Introduction to Ostracon 3: R.Mutt: Writings about Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) and its aftermath.

Only a few people had access to the moment on April 10, 1917 when Marcel Duchamp’s pseudonymous work Fountain, signed R. Mutt, was refused by The Independents Salon. Without revealing his authorship, he resigned as a juror and walked away. In the century that has followed, Fountain has become the most important modern ceramic artwork in the world and also been voted, again and again, the most significant art object as well by critics and curators. It is the unchallenged Queen (it is a feminine receptive form) of the avant-garde modern art object canon and reigns supreme celebrating the 100th year anniversary in its reign over sedition in art.

Julian Wasser, Marcel Duchamp at the Pasadena Art Museum, Los Angeles, 1963, (c) 1962 Julian Wasser

By 1978 all those present were dead, but one. I had the unique privilege of being a friend of Beatrice Wood, the potter, twenty-four years old in 1917 and who died in 1998 at the age of 105. Though not a juror, she was with Duchamp and present when the jury deemed Fountain unworthy of exhibition even though the rules stated that any work submitted would be accepted if it was signed and the required fee was paid. But even for the avant-garde, there are limits. Wood told me that she either saw or imagined a look of barely concealed delight on Duchamp’s face when the work was rejected. This was the perfect outcome for his intervention.

There is something about being a witness or knowing a witness to the earth-shaking moments of history that gives one an added sense of intimacy with the moment, almost being there. Discussing this moment with Beatrice was like touching the hem of God. Her comments in The Blind Man, written in tandem with Duchamp a few weeks after the cause célèbre, are quoted in bold in the photocopy. “As for plumbing, that is absurd. The only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges.”

In the early 1970’s in the ceramics community, I was almost alone in loving this vessel; literally a pot to piss in although I had my doubts about it being a con job as well. It was trotted out at ceramics conferences as an object of derision. “Exhibit A:” the decadence of art vs. the useful moral superiority of the functionalist Leach School.

Now iconic, it is endlessly loved and lampooned, hence the the title of this introduction is “Mona Lisa of the Loo.” What makes Da Vinci’s painting the best known artwork in existence? Is it some technical quality that makes it the best Florentine painting? No, it’s an accident of familiarity, the endless repetition of the image in reproduction that gives a huge swath of people across five continents a sense of “knowing” this painting. It joins those who know a lot about art and those who know little; democratizing culture in the manner of a cliché. That is what drew Duchamp to appropriate Mona in his own art. Fountain does the same.

Everyone has an opinion about Fountain, whether negative or admiring. Yet no matter how many times we see it on computer screens, in museums and in print publications, drawn on bathroom walls, its power reconnects and remains mysterious. And like Mona, Fountain’s form is feminine. It’s totally alluring and sexually titillating, and its smile, though big, broad and white, is every bit as enigmatic as that of Mona.

It has provoked hundreds of thousands of homages and comments. Some as jokes, cartoons, some satirizing conceptual art as idiocy, but a healthy number from artists recognize it as shrine to a shattering moment when our limits for what is art changed forever, for better and as much for worse. They have come from artists as diverse at Bruce Nauman, Hans Haacke, Zhou Wendou, Ai Weiwei and Lady Gaga. From the profane in a men’s sleazy public toilet (appealing to men because it is a comfort station. It promises relief, so its karma is generally positive) to, in Kathleen Gilje’s case, the sacred as a religious relic.

Kim Dickey, Jacqueline’s Lady J, 1997. Framed photo, 4″ x 6″, Photo courtesy of India Dunnington.

A giant version, Johnny on the Spot (2003) by Saul Melman at Burning Man (alas, I never saw it, I didn’t become a Burner until a few years later) inflates the work to its true metaphoric scale, looming over both modern and contemporary art. It’s also a clever pun for the architecture of a pissoir or vespasienne, the structure introduced in Paris in 1830 that provides support and screening of urinals in public spaces. Inside this massive artwork, visitors sensed an invitation to urinate.

Those who seek to appropriate or quote its celebrity frequently, often miss the point. It’s about semen and not shit. So, the seated toilet is not the same thing. Not even close. Why? Aside from the reason already given, because it removes the gender specificity of this work. It mixes solids and liquids which was not Duchamp’s intent. Fountain exists to receive male fluids in a female container. Feminists drolly argue that has been woman’s role for millennia.

Yet ceramist Kim Dickey has breached this divide with her Lady J’s, giving women equal standing. But overall it is about male dominance and vertical access. What is fascinating is to read Paul Franklin’s essay in this anthology “Object Choice” on its emblematic role in gay “tea room” (public bathroom) sexual practice that incorporates both discharge of urine and semen. One doubts that Duchamp had this in mind as a central issue, yet as a worldly man, inquisitive of human behavior, he could not have been unaware of these activities in public arenas.

Gay activists, Scandinavian artist-duo, Ingar Dragset and Michael Elmgreen, dealt with this in the spaghetti plumbing of Gay Wedding (2011), explaining same-sex unions by uniting two porcelain urinals to a single meandering pipe. In this case fluid flow is shared, male to male, in both directions.

When Fountain it is placed on its back it reveals a full-frontal, rude, stubby tube where the metal plumbing would be attached. It has a phallic quality, but truncated, cut-off, giving it an unhappy almost painful, Hedwig and the Angry Inch, quality. None of this is explicitly stated and it could well be that we, Fountain’s voyeurs, are bringing far too much to the table? Maybe, but isn’t that what effective conceptual art must do…start a process that one can enlarge upon and expand into one’s own mind?

Drawing in a public restroom, artist and photographer unknown.

One thing we know is that it was not meant to be was pretty. Duchamp has been clear that there was no aesthetic intent. However, he knew that aesthetic judgment is inescapable. Artists declaring their work to be beauty-free zones throughout modernism have never been able to attain this status. Donald Judd’s minimalist sculpture was meant to escape beauty. Now, it is now achingly almost decadently beautiful—sumptuous color, perfect line, silken texture and classic proportions. The eye never fully neutral, it is always judging the impact, even if subconsciously, of anything visual that enters one life. And if something is ugly, that too is aesthetics. It can be held back for while by intellectual argument, as a affectation, but finally, all art succumbs.

This is true of Fountain. Two weeks after its rejection, the first accolade for its sexy visual appeal appeared in The Blind Man magazine. Louise Norton, in the title of her article called it “The Buddha of the Bathroom.” One can see the vague similarity of line/garments flowing from a seated figure. But that is not the point. The best figures of Buddha were then, as now, considered amongst the highest and most transcendental art expressions in Asian culture. That means that it took Fountain just 14 days to fall to the politics of the human gaze.

Fountain is handsome, beautiful, lyrical, familiar, insouciant, welcoming, sculpturally powerful, functionally perfect in pure white clothes. In part it appeals, at least for me, because the physical object is not the work of an artist. It was designed by a person in a factory. He (the likely gender) arrived at the form through a thicket of rules; the architecture of a public bathroom (urinals were rarely in private homes in 1917), the male body, penis length, functionality, liquid flow, hygiene, the fit and flow of glazing and lastly, the ultimate arbiter—the kiln. But give that this process was largely objective, we cannot assume that the designer did not also deliberately ponder by the lyrical flow of line and contour and sensuality of form.

There are some Victorian urinals where the designer was deliberately making a work of decorative art. See Ezra Shale’s essay in this anthology ‘“Decadent Plumbers’ Porcelain’” explores this area. So does contemporary artist Pablo Echaurren who presented a maximal blue and white punk-Aztev version. But what makes the original so powerful is its blandness. It is only meant to be noticed for a distinct purpose, but we cannot assume that the designer did not mean it to be pleasing visually in only the most simplistic sense. The objectivity of the process created a minimalist object, and thereby achieved in its day a certain industrial modernity. Again, aesthetics cannot be sidestepped.

The Fountain also crossed three aesthetic value boundaries. It is an art object, the original is a piece of industrial design (happily a second extant and exact urinal was recently found in St. Louis proving its factory origin and thereby dispensing the silly notion that Duchamp had Fountain crafted to look like a factory product) and then he made, or approved the making of, four variants all of which were handcrafted.

These three boundaries—art, design, craft—can all be third rails depending upon which direction one is traveling. From ceramics, one encounters the material apartheid that banned ceramics in fine art, which amazingly endured until the 21st century. Neither studio ceramics nor art approved of design as a higher calling. So the piece in its variant manifestations had built-in categorical taboos that had little to do with urine. This complexity allows it to retain a remarkable resilience of currency in art today.

Much has changed since 1985, when at the 4th International Ceramics Symposium in Toronto Doris Shadbolt repeated Leopold Foulem’s dictum, but it still defines the border crossings in a lingering art-vs-craft debate and, more broadly, the lines of demarcation for conceptual art as well:

Craft is what one pisses in.

Art is what one pisses on.[1]

Kathleen Gilje, Sant’Orinale (Saint Urinal), Gesso, red clay, gold leaf, embossed, gouache and oil paint on wooden panel. 16 3/4″ x 13″. Courtesy of the artist and Francis Naumann Gallery, NYC.

This anthology has been a gestation for a long time, a decade in fact, and I doubt it would have been realized without the arrival of my capable, far-sighted co-editor and collaborator Marie Claire Bryant. As much thanks goes posthumously to the beloved Mama of Dada, Beatrice Wood, Dada’s great scholar Francis Naumann for decades of friendship and tutoring, his gallery director Dana Martin, Alex Matisse for opening doors, Séverine Gossart and Antoine Monnier at the Duchamp Foundation, and all the contributors to this volume.

This anthology has been a gestation for a long time, a decade in fact, and I doubt it would have been realized without the arrival of my capable, far-sighted co-editor and collaborator Marie Claire Bryant. As much thanks goes posthumously to the beloved Mama of Dada, Beatrice Wood, Dada’s great scholar Francis Naumann for decades of friendship and tutoring, his gallery director Dana Martin, Alex Matisse for opening doors, Séverine Gossart and Antoine Monnier at the Duchamp Foundation, and all the contributors to this volume.

Footnote:

[1] Doris Shadbolt, “The Transparency of Clay” in Garth Clark Ed. Ceramic Millennium: Critical Writings on Ceramic History, Theory, and Art, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 2008, p 25.

Add your valued opinion to this post.