NEW YORK––It is difficult to know how to open this essay, whether by saying that we have just experienced a momentous paradigm shift, or rather by simply noting that the inevitable has finally come to pass. I refer to the appearance of six ceramic works by George Ohr in one of the newly organized galleries at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, in a room displaying modernist masterpieces by Seurat, Munch, Rousseau, Ensor, Redon, Gauguin, and most notably one of the museum’s most beloved attractions, Van Gogh’s The Starry Night. Ohr’s works in this context are most intriguing, and he certainly holds his own in this august assembly, suggesting that his claim that he was, “the greatest art potter on earth” is perhaps not too far fetched – and do note that he specifies “art potter.”

For some time now major museums have been exhibiting ceramics on equal footing with other art forms, as in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, which pioneered such juxtapositions without much fanfare. And of course exhibitions from cultures where ceramics play a major role – as in the Japanese, Chinese, and Korean galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art – have long intermingled ceramics with the other arts. Over the past several decades ceramics have slowly but surely entered the international art world, inspiring some commentators, lead by Garth Clark, to insist that the art/craft distinction – long at the core of criticism, theory and polemic concerning ceramics – is now obsolete. Thus the presence of George Ohr in one of the preeminent MoMA galleries is – while not an originary gesture – most certainly a powerful symbol, a rethinking of aesthetic paradigms, a consecration of studio ceramics by the very institution responsible for one of the major (if not the major) narratives of Modernism.

Juliet Kinchin, Curator in the Department of Architecture and Design, explains this surprising curatorial choice: “The decision was the result of ongoing discussions between curatorial staff in different departments. We wanted to break down compartmentalized ways of looking at different media, to combine the familiar and unfamiliar, and to find works of a similar date that would resonate with each other – whether in terms of the artists’ personal connections, or their dominant concept, form, and materiality. The inclusion of Ohr fitted on a number of counts, not least being able to introduce an American artist in the first of the collection galleries.”

MoMA, as readers of CFile well know, has generally not been kind to “studio” pottery, having subsumed ceramics within its Architecture and Design collections, thus generally limiting the field to industrial design. Major exceptions are: (a) those artists who, though not known primarily as potters, produced significant works in the field (Gauguin, Picasso, Miro, Noguchi); (b) certain artists who, though fundamentally ceramists, were mistakenly classified otherwise (notably Lucio Fontana); (c) those rare exhibitions that included studio pottery but categorized the works as sculpture (as when Peter Voulkos participated in MoMA’s New Talent series in 1960). Rare were the works of studio pottery that emerged outside these confines to find their place amidst the other arts.

Consider The New Japanese Painting and Sculpture (1966), one of the first major exhibitions in the West on this theme. The show included four ceramic pieces by Yagi Kazuo, notably A Cloud Remembered (1962) already in the MoMA collection, as well as two terra cotta works by the lesser know Tsuji Shindo – a Zen priest whose work influenced Yagi and the avant-garde Sōdeisha group Yagi co-founded. However, there is no mention in the catalogue of the realm of ceramics, since the pieces in question were unequivocally subsumed under the category of “sculpture,” as indicated by the show’s title. Both Sōdeisha and MoMA wished to realign traditional categories, but for different reasons. Sōdeisha members went to great pains to differentiate their works from modernist sculpture, precisely in order to remain within the world of ceramics (yakimono), going so far as to create a new term for such creations, obuje-yaki (fired object, a portmanteau word derived from objet, the French term for object and yaki, the Japanese word for firing). They saw themselves as potters working at the formal limits of ceramics. MoMA, to the contrary, saw them as modernist sculptors working in clay. Thus the inclusion of such artists in MoMA exhibitions was done in such a way as to omit the complex history and aesthetic specificity of Japanese ceramics.

There have been exceptions, and Juliet Kinchin offers a nuanced viewpoint: “While not a major curatorial concern, studio pottery has in fact featured in MoMA’s collection and exhibitions for many decades. A Department of Manual Industry directed by Rene d’Harnoncourt was established in 1944 in parallel with the Department of Industrial Design (both were later merged into the Department of Architecture and Design). It dealt with matters of design and craftsmanship in hand-made articles, and also ‘the problems which affect the free function of the craftsman’s skill and talent in the post-war world.’ In MoMA’s mid-century Good Design program industrial design and handcraft were not seen as antagonistic and there were small exhibitions of ceramics by the Natzlers, Peter Voulkos, Kitaj Rosanjin and Lucie Rie, for example. Art pottery of an earlier period was collected as part of the Museum’s interest in art nouveau and the arts and crafts movement.”

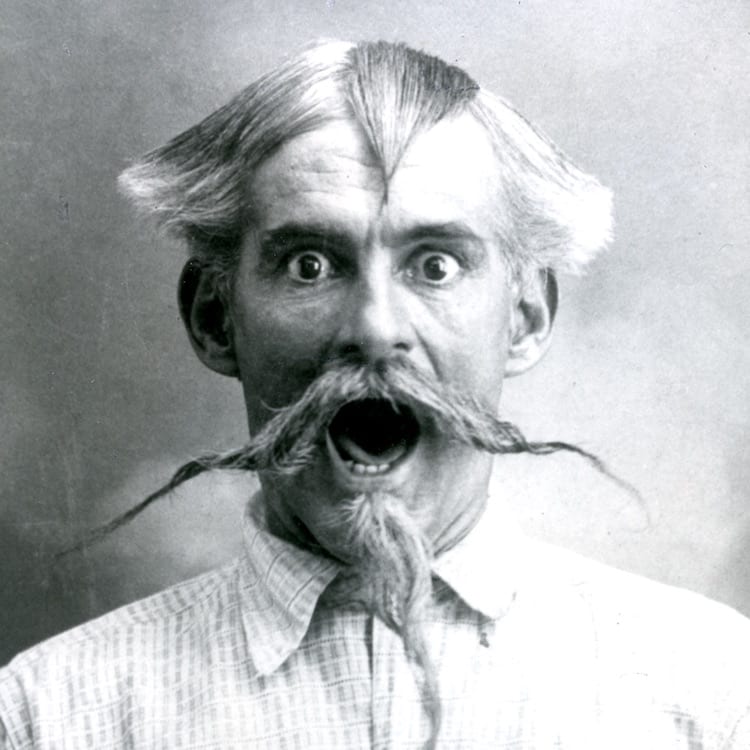

Concerning George Ohr at MoMA today, we might ask why, in the context of early European modernism, an obscure and long forgotten American potter was chosen for display, rather than, for example, a French modernist ceramic artist such as Ernest Chaplet, Jean-Joseph Carriès, or Auguste Delaherche. One might even imagine adding to the mix a ceramic work by Gauguin, who had a close relationship with Van Gogh, to further complicate matters. Superficial as it may seem, it is hard not to think of the obvious juxtaposition of “The Mad Potter of Biloxi” with Van Gogh, that icon of mad genius, consecrated as such in Antonin Artaud’s extraordinary text, Van Gogh, the Man Suicided by Society (1947). The formal relations that link Ohr and Van Gogh are relatively easy to assess: the sinuosity of the lines, the dynamism of the compositions, the distortion of accepted forms, the chromatic experimentation. Juliet Kinchin concurs: “Indeed, as that title of the ‘Mad Potter of Biloxi’ suggests, the psychologically expressive forms can readily be connected with the swirling clouds and landscape of Van Gogh’s The Starry Night – visitors have to look at and walk past the Ohr ceramics to get to Van Gogh’s masterpiece which is installed beside Rousseau’s The Sleeping Gypsy on the back wall of the gallery, so these exhibits are asking to be connected. I think they also share a more general ‘outsiderish’ feel.”

I would love to spend an hour or so eavesdropping on people’s reactions, though I suspect that old aesthetic habits and prejudices die hard, so that many would probably just wonder what six pots are doing in the middle of a room containing so many masterpieces. One might also consider how different the reactions would be if some of Ohr’s more extravagant works were displayed, so as to more ostentatiously reveal his extraordinary technique and unique vision. Concerning the psychological resonances between Ohr and Van Gogh, I would just make the cautionary point that at least since the publication of Artaud’s text, the general public has tended to see Van Gogh (as well as Artaud) as the epitome of mad artistic genius, which is to say many approach his work more as attraction or myth than art, with all the pitfalls that this entails. As for George Ohr, it is difficult to know whether he was mad, eccentric, or just a great showman, and Salvador Dali’s quip is pertinent here: “The only difference between Dali and a madman is that Dali is not mad.”

One might quibble about certain aspects of the installation, such as the low vitrine, necessitating that the viewer kneel in order to see the frontal forms, which would accord with viewing protocols in Japan, but which remains unseemly, if not prohibited, in American museums. More crucial, it is perhaps a shame that the works are rather sedate, far from Ohr’s most extravagant productions. But this is precisely what makes the installation so special to the pottery world: however unlikely it is that these bowls, pot and pitcher would actually be utilized, they are nevertheless on the borderline of functional objects, thus their presence at MoMA calls into question the old dichotomies of functional/non-functional, pottery/sculpture, craft/art.

As Garth Clark insists, George Ohr was, “rejected by craft, rescued by art.” If the MoMA installation had occurred in the design galleries, it would probably have gone unnoticed save mainly for some ceramics aficionados, and the aesthetic impact would have been considerably narrower. But for Ohr to enter the mainstream of High Modernism – as written, for better or worse, by MoMA – is the ultimate vindication of the role of ceramics in the history of modern art, thanks to a “mad” potter and an “eccentric” curatorial vision.

Allen S. Weiss is the author and editor of over forty books on landscape architecture, gastronomy, outsider art, sound art, and experimental theater, most recently The Grain of the Clay: Reflections on Ceramics and the Art of Collecting. He is Distinguished Teacher in the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University.

Ohr’s inclusuion @ MoMA next to modern masterpieces is the direct result of several decades of scholarship, as well as Ohr’s acceptance into the secondary marketplace. Study and money made finally Ohr visible to the mandarins who control the modernist narrative. It is the same for certain fiber artists like Sheila Hicks and Ruth Asawa. Kudos to the people like Martin Eidelberg, Robert Judson, and Garth Clark who labored so long to make this happen. What began with the publication of Judson’s “The Arts and Crafts Movement in America 1876-1916” in 1972 has finally come to fruition. Partly. Much craft remains invisible and illegible. And it took nearly half a century.