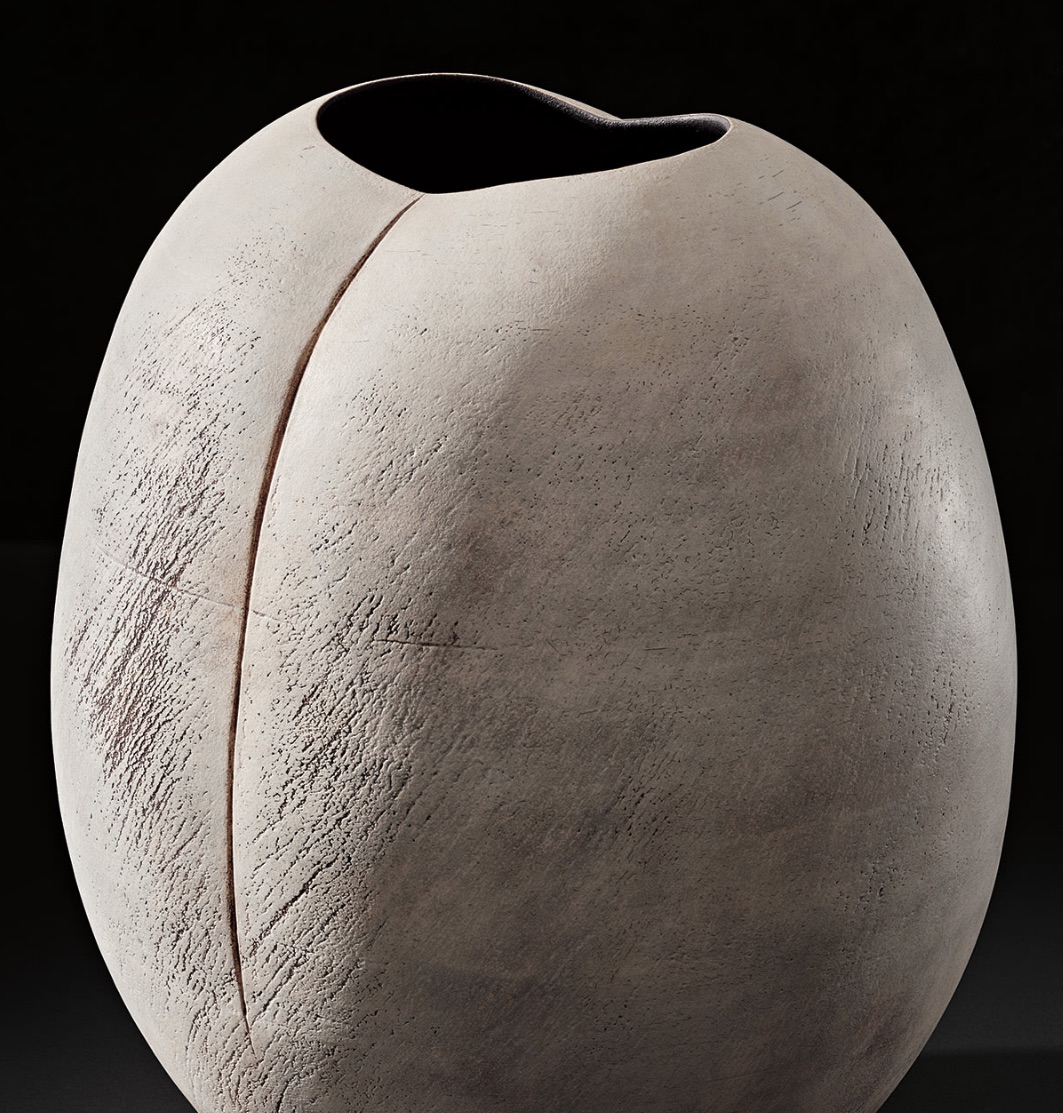

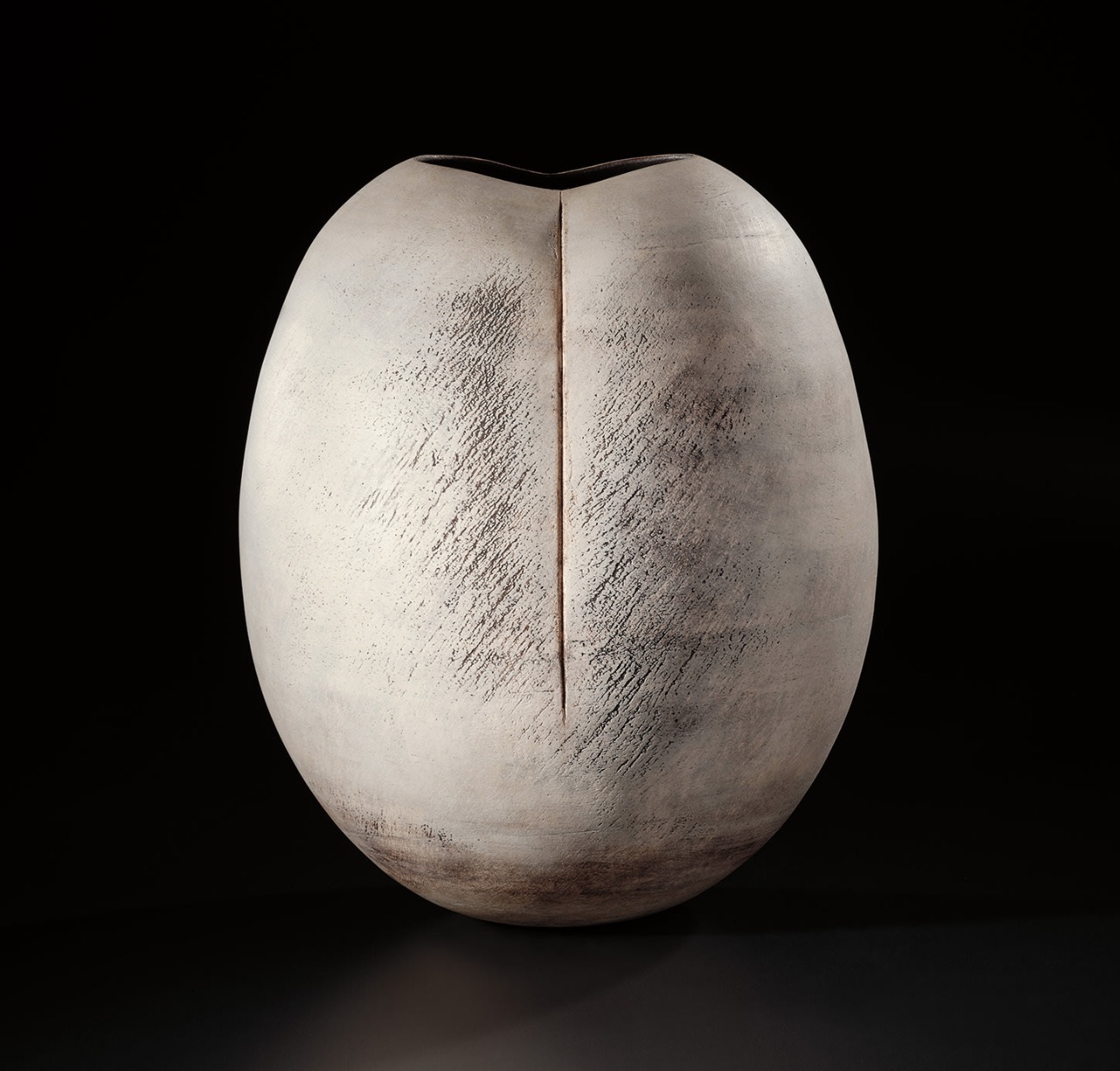

Lot 82

Hans Coper

Monumental ovoid pot

1968

Stoneware, layered porcelain slips and engobes over a textured surface, a deep vertical

indent to each face, the interior with a manganese glaze.

46.5 x 38.5 x 38 cm (18 1/4 x 15 1/8 x 14 7/8 in.)

Estimate: £80,000 – 120,000

Sold for £651,700

The last two years we have lost a number of the collectors of ceramics whos passion and connoisseurship for modern and contemporary ceramics were vital in the rise of ceramics to its current status as art: the George E. Ohr collectors, Marty and Estelle Shack; Sandy Grotta (housed in a domestic temple by Richard Meier), Alan Chasanoff (whose collection now lives at the Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte), and Bob Ellison who will be featured in the next issue (part of his gift to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York is currently on view). John Driscoll whose eye for early studio pottery in particular, was unequalled, adds to this distinguished list. A selection from his collection went on sale yesterday in a joint auction by Phillip’s and MAAK in London (see the accompanying Marketplace feature by Garth Clark about the record making event). Below is a short touching tribute by Glenn Adamson.

Hans Coper

‘Poppy Head’ pot

circa 1957

Stoneware, layered porcelain slips with manganese design around the lip and interior.

20.8 cm (8 1/4 in.) high, 14 cm (5 1/2 in.) diameter

Estimate: £6,000 – 9,000

Sold for £151,200

Hans Coper

‘Cycladic’ arrow form

circa 1972

Stoneware, layered porcelain slips and engobes over a textured and incised body, the interior with a manganese glaze.

22 cm (8 5/8 in.) high

Estimate: £40,000 – 60,000

Sold for £277,200

Like many vital and flourishing things, John Driscoll’s ceramics collection began with an egg. The year was 1976, when he was a doctoral student at Penn State. In one of those fortuitous turns of fate that sometimes shape people’s lives, he happened to be a graduate assistant at the university museum when its visionary director, Bill Hull, curated a show called Twenty-Four British Potters. John, asked to unpack the crates, promptly fell in love. Despite his limited budget at the time he quickly acquired pieces by eight of the potters, including the great Lucie Rie.

There was another pot that captivated him, but at $180 simply seemed out of reach: a speckled white ovoid with a sharply articulated two-stepped rim, and a celestial blue interior. It was by Liz Fritsch, best known for her dazzling patterned vessels. In this early work, she already demonstrated her absolute command of volume and profile, a sublime serenity. John had to have it. After agonizing for a while, he took the plunge (like a lot of other collectors, he knew he was one when he got in just over his head). It remained a personal favorite in his collection, together with a postcard Fritsch sent to him bearing the image of three perfect bird’s eggs on its cover. The career of a connoisseur was hatched.

John told me this story — and many others, just as memorable — during the preparation of Things of Beauty Growing, an exhibition at the Yale Center of British Art and the Fitzwilliam Museum, which drew substantially on his collection. His involvement in the project was extraordinarily generous, all the more so because John had always kept his interest in ceramics more or less private. This was partly for personal reasons — he wasn’t the type to seek the limelight — and partly an ethical matter. As the head of Driscoll Babcock, New York’s leading gallery of historic American fine art (and the oldest continuously operated gallery of any kind in the city), he felt that he should keep his collecting activities out of the public eye, and quite discrete from his activities as a dealer.

At one point, when discussing the philosophy of the Japanese mingei movement and its preoccupation with the figure of the unknown craftsman, John said to me that “genius can be anonymous.” He conducted himself accordingly. At once deeply erudite and totally self-effacing, he assembled one of the world’s great collections in any artistic category, quite quietly, without making a fuss. His vision was at once simple and, given the relatively marginal condition of studio pottery in the late twentieth century, somewhat radical. He set out to acquire the very best objects by the very best makers, and let them speak for themselves.

Now, we have the opportunity to hear that story in full. The auction catalog, The Art Of Fire: Selections From The Dr John P. Driscoll Collection affords a comprehensive view of twentieth-century British studio pottery. Each object, selected with rigor and discretion, marks out a position within a complex field of aesthetic achievement. The governing dialectic is the familiar one between modernism and traditionalism, with Lucie Rie and Bernard Leach seemingly exemplifying these two competing values. A closer look, however, reveals the falsity of this opposition — or at any rate, the degree to which British potters achieved a union of these seeming alternatives.

Text by Glenn Adamson courtesy of Phillip’s and Maak. Photograph of John Driscoll by Emily Driscoll.

Photo: Emily Driscoll

Fabulous collection some of which I haven’t see before. Thank you Dr Driscoll and C-File.

Makes me thinking of Jacob van Achterbergh, Dutch collector. When his collection was sold there was not yet a real market. Times are changed. There is a beautiful Geert Lap for sale at the PAN , Rai Amsterdam on the moment- 20.000 Euro.