By Jenni Sorkin

Nicki Green (b. Boston, 1986) uses ceramics to make space for the trans body. She utilizes its properties of plasticity and transmutation, or the action of changing into another form, as raw clay itself is a material with alchemical properties, becoming something spectacularly other, once fired and glazed. Her mixed-media sculptural works render the body metaphorically, thematizing sexuality, religion and identity. An emerging artist who is currently in the first decade of her career, Green has already garnered high wattage visibility through her inclusion in the prominent triennial, “Bay Area Now” (2018), held at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco, and Craft Contemporary’s second Clay Biennial, titled “The Body, The Object, The Other,” (2020), in Los Angeles.

Metamorphosis and Jewish identity as the primary drivers of Green’s content. Clay is key to rendering the body metaphorically, but also create a morphology of form itself, that, is revising and re-shaping form. To this end, Green reworks ritual objects, inventing them anew, for an expanded, multigenerational, non-binary audience that might partake of them, or find meaning in the sanctity of inclusion itself. Not exclusive to Judaism, religious traditions worldwide enforce traditional male-female gender binaries, which become a barrier to non-binary participation, access, and belonging. Green’s significant and original work functions as a series of challenges to traditions and conventions in three simultaneous arenas: the social rigidity of gender presentation, Judaism, and functional ceramics. Transformation is the subtext of Green’s work, in particular, her use of form itself as a material means of enabling a poetic response to the transgendered body.

From the late 1960s forward, gay and lesbian artists embraced the figure the centerpiece of their practice, mining the construction of identity through the direct representation of the queer body. Photography, video, and film were the dominant modes of exploration, across a wide range of practices, including documentarians like Joan E. Biren (JEB) (b. 1944) and avant-gardists alike, filmmakers such as Kenneth Anger (b. 1927) and Barbara Hammer (1939-2019). In photography, Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-1989) and Catherine Opie (b. 1961) utilized portraiture as a way to affirm the social visibility of queer people, photographing their own homosocial, underground communities. For Mapplethorpe, this consisted of representations of mixed race couples, BDSM sexual practices, sculptural nudes, and self-portraiture. Influenced by Mapplethorpe’s oeuvre, throughout the 1990s, Opie produced portraits of non-binary couples, the BDSM lesbian scene of San Francisco, provocative self-portraits, and lesbian domesticity nationwide. Both photographers oscillated between testing a viewer’s tolerance and subsequent sense of empathy, or, conversely, utter dis-identification. Collectively, this grouping of progenitors was extremely influential to future generations of queer artists, including Green. As she underscores, “Seeing representations of gender variance in such a direct way was what allowed me and allowed [other] trans folks to understand themselves in the world.”[1]

Subsequently, these pioneering queer artists made it possible for Green to pursue a more haptically-driven, or touch-centered, practice, keenly focused on object-making rather than image-producing. For instance, Green’s stoneware Kiddush (2016), the Hebrew word for “sanctification,” remakes the ceremonial wine chalice with layer-upon-layer of purple imagery that pays homage to the sacred actions and sacrifices of previous generations of LGBT Jewish activists and martyrs. The color purple alludes to the LGBT embrace of the terminology “lavender menace,” an epithet aimed at radical lesbians fighting for visibility within the American feminist movement of the 1970s. The phrase itself was coined in 1969 by the renowned feminist writer and activist Betty Freidan, who was herself heterosexual and Jewish. Green utilizes open palms framing an embellished upside down triangle, another reclaimed symbol, forced upon Jewish homosexuals by the Nazis throughout their reign of terror. The open hands are themselves a reference to the Hamsa, a palm-shaped amulet often hung in Jewish homes or worn as jewelry, as a means of deflecting or warding off the evil eye. The actual referent she utilized was the priestly “lifting of the hands,” initially a Jewish tradition early on appropriated by Christianity (and long associated with it). This verbal benediction is denoted through the split fingers (here, inverted to signify the queer triangle), which are sometimes referred to as a lattice through which G-D can look upon a congregation. Such a pattern, what Green calls the “hexagram lattice” is rendered and retained throughout her recent object making.

In 2019, Green was a Resident Artist at the highly selective Arts/Industry program, hosted by Kohler Center for the Arts in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, where the Kohler factory setting offers artists the tantalizing potential to grow the scale and scope of their artistic production. Kohler itself is a company renowned for its kitchen and bathroom fixtures, producing sinks, toilets, and faucets for commercial and residential clientele. Influenced by the setting itself, Green fused the dynamism of gender politics with domestic plumbing and its penchant for hybridity, making double urinals and bidets with decorative flourishes such finnials, faucets, and miniature toilets, such as the highly charged work, A Discrete History of Intimacy and Violence (double urinal basin with faucets) (2019), in which she partially sketches the partitioning of two occupied toilet stalls, in which gender is only potentially revealed through the size and style of shoes. In this scenario, each viewer of the work becomes a voyeur, peeking in the gap under the door so as to discern habitation. This presence on either side of the door causes an automatic tension in dialogue with the sculpture’s evocative title: restrooms are intimate spaces in which our own plumbing is unmasked: the forced reveal of genitalia due to the history of what French psychiatrist Jacques Lacan called, “urinary segregation,” women and men divided by their anatomy. The Canadian queer theorist Sheila Cavanaugh, whose work has been influential to Green, revises this binary, calling the bathroom a “gendered architecture of exclusion,” that defaults to whiteness, associating its aesthetics with a symbolic purity, or, as Green points out, also defaults to acts of violence and aggression toward trans people who are misunderstood as attempting to “pass” as an alternate gender identity, or are rejected for the lack of clear male/female delineation in their gender presentation.[2]

Green’s sculpture, then, provides a direct critique of the recent transphobic, exclusionary policies regarding bathroom discrimination in which trans people were not initially permitted to utilize the facilities which matched their gender identity in state buildings (a hot-button legislative issue in the state of North Carolina, for instance, known as the “Bathroom Bill”). Again, there are many layers at work here: the frilly decorative shapes and doodles taking up space, a way to nod at the prim conventions associated with 18th century European porcelain objects, a long ago, but fraught moment when porcelain carried aesthetic and political efficacy simultaneously. The miniature toilets reference bidets, French washbasins invented to clean and freshen up the genital area, and long associated with prostitution, or another marginalized population, the sex worker (often today, one of the mainstay occupations of trans folks). And finally, a reverent kind of reference or kinship to the queer artist Robert Gober, who produced abject sinks and drains throughout the 1990s, though his were minimalist and industrially produced, rather than treated as a drawing surface. Green articulates her process and careful thinking, which reifies the idea of the toilet as a repository for waste. As she writes: “While making these pieces, I thought of them as Frankensteined Kohler product; I used mostly waste materials (like literally digging through the “cull” or waste bins for wet, failed product to cut up and reassemble) to make washing/ablution ritual objects that affirm the queer body.”

During this same span of time, Green activated the mikveh, a Jewish ritual bath in which observant women habitually dip as a form of ritual immersion, arriving at purity after menstruation. There are also other uses of the mikveh: it is a bath utilized prior to conversion and marriage ceremonies, and before the Jewish High Holidays.

In 1977, at the New York alternative space Franklin Furnace, the performance artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles made the first known avant-garde performances around mikveh, exploring its entwined spiritual and religious significance as both a feminist and an observant Jew.[3] Unlike Ukeles, however, Green decided not to use her own body in the creation of her work. Instead, given its utilitarian materiality— made entirely from white porcelain—she treated the mikveh as an architectonic space. One of the staunch requirements of functional vessels is that they perform as “water tight,” that is, they don’t leach water through dripping or leaking. Green’s mikveh pieces are the opposite of this ceramic ethos.

Mikveh for Mychotheology (2018), a mixed media earthenware sculpture is one such piece, approximating a wash basin or ewer that is split in half, lined with decorative white tiles in which androgynous figures ring the interior. They are depicted in a vaguely ancient schema, all in profile and without individual features, as though part of an archeological mural program inscribed upon temple walls. A single androgyne stands, a flat disk encircling their head, doubling as a head covering or medieval halo. All the others squat in what seems initially to be a repose of prayer, but in actuality, is a harvesting of mushrooms.

Mycology is the study of fungi, and mushrooms are themselves a fungus, and one of Green’s key, early symbols. She created a number of mushroom pieces, such as Morel Figure (2016), referencing the porosity and replication practices of mushrooms themselves, which, as spores, emerge all at once, an entire being, rather than a seedling that sprouts over time. This idea of full emergence, rather than piecemeal growth, becomes an important metaphorical rendering of the trans body, a means of establishing wholeness and radiance all at once—total acceptance, so to speak, rather than a careful and quiet unfurling of reveal: a single stem, the underside of a leaf. Green’s mushrooms are carefully androgynous: rendered as sensuous, multipartite organisms, wholly reflective of the simultaneous means of sexual and asexual reproduction possible in spores, which have web-like networks below the surface, their root systems akin to the idea of a communal support system that often goes unseen in the lives of queer people.

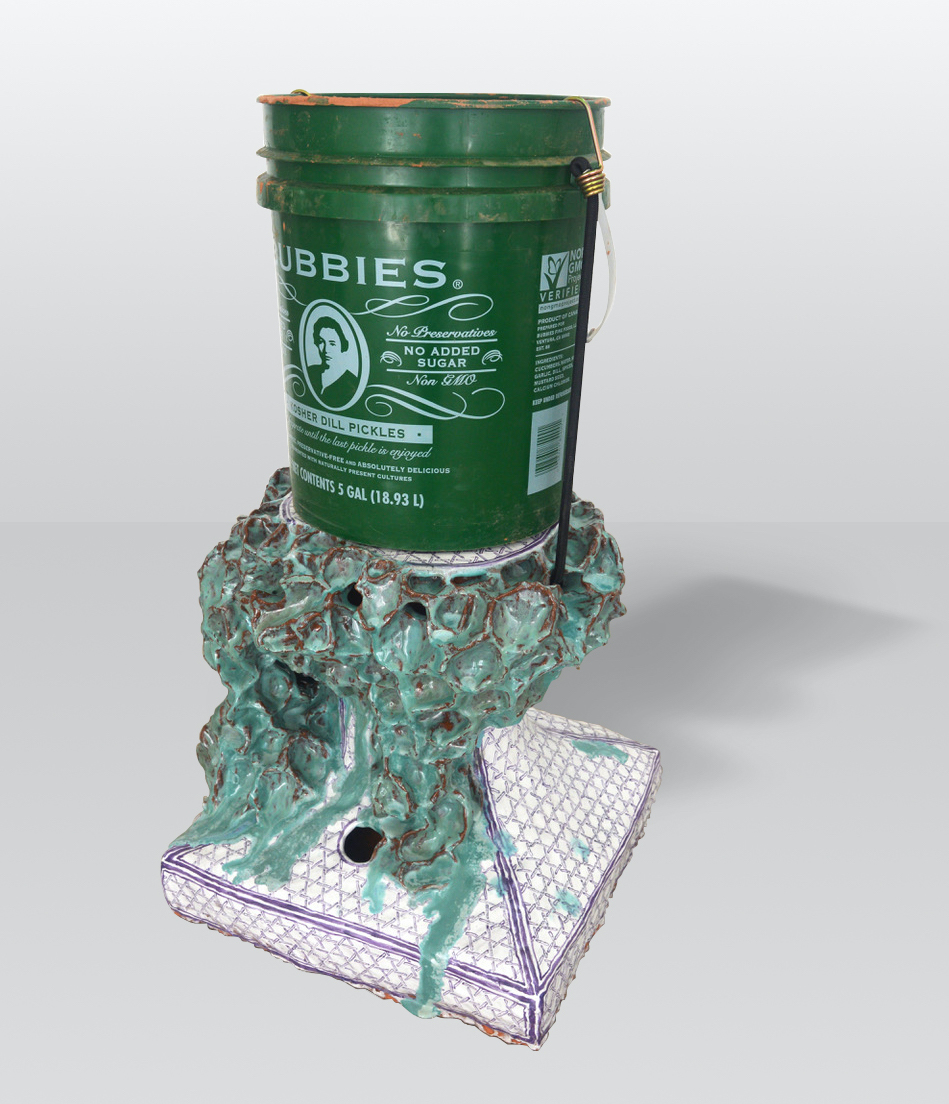

Addressing the gender complexities of Jewish death rituals, Pillar of Earth (all 2020) is Green’s most recent body of work. A series of ten bucket stands, Green extends the timeline of ritual cleansing to the moments beyond life, including the washing of the recently deceased. In the midst of a worldwide pandemic, this has strong resonance. Each work bucket is itself a found object, emblazoned with a contemporary logo, adapted to a wide variety of functions, from carrying tools to storing kosher pickles. Each rests on a handmade ceramic pedestal, embellished with a textured honeycomb patterning and her signature hexagram latticework with purple “grout.” These works are based upon the tradition known as “Shemira,” the washing and watching over the body from death until burial, a liminal, transcendent time in which certain rites are performed in order to guard the spirit, still considered present in the body. These guardians are gendered positions: a shomeret for women, and a shomer for men. With these works, Green provides a pathos for the disparity—and despair—of how a Jewish non-gender conforming person such as herself would be attended, and perceived. These works highlight the elegiac mysticism and transcendent beauty of Jewish ritual. Anything less is considered a humiliation of the dead.

Green’s sculptural objects amplify a deeper spiritual significance while honoring the history of otherness and marginalization, threefold: in the materiality of craft, in Judaism as a minority religion, and trans identity as a sexual minority, bringing them to center of conversation through her deeply conversant knowledge of Judaism, and the histories of functional and ritual objecthood.

[1] Zoom conversation with the author, August 5, 2020.

[2] Sheila Cavanaugh, “Gender, Sexuality and Race in the Lacanian Mirror: Urinary Segregation and the Bodily Ego,” in Psychoanalytic Geographies, Paul Kingsbury and Steve Pile, eds. (London and New York: Routledge, 2014), 323.

[3] See David Sperber, “Mikva Dreams: Judaism, Feminism, and Maintenance in the Art of Mierle Laderman Ukeles.” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5.2 (Fall 2019), online. https://editions.lib.umn.edu/panorama/tag/david-sperber/. Accessed August 20, 2020.

Add your valued opinion to this post.