NEW YORK––Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950–2019, at the Whitney Museum, seeks to foreground “how visual artists have explored the materials, methods, and strategies of craft over the past seven decades. Some expand techniques with long histories, such as weaving, sewing, or pottery, while others experiment with textiles, thread, clay, beads, and glass, among other mediums. The traces of the artists’ hands-on engagement with their materials invite viewers to imagine how it might feel to make each work.”

It is ironic that when the craft world tried to back away from its title, the fine arts took it over, shifting the word craft from being a noun to a verb. Also, this exhibition is the first time (aside from recent Biennials) that ceramics has been showcased in a major sense at the Whitney since the early 70’s. It is a toss-up as to whether the Whitney or MoMA have been the most hostile, the most provincial, in excluding ceramics.

Cfile even awarded the museum with the The Puddled Cone Award for Exceptional Illiteracy in the Ceramic Arts in 2015 for leaving ceramics out of their major survey of American art that opened their new home. With Making Knowing, curated by Jennie Goldstein, assistant curator, and Elisabeth Sherman, assistant curator, with Ambika Trasi, curatorial assistant, provincial attitudes may be changing. The curators note:

“While artists’ reasons for taking up craft range widely, many aim to subvert so-called “fine art,” often in direct response to the politics of their time. In challenging accepted ideas of taste—whether by embracing the decorative or turning away from traditional painting and sculpture in favor of functional items like bowls or blankets—these artists reclaim visual languages that have typically been coded as feminine, domestic, or vernacular. By highlighting marginalized modes of artistic production, these artists challenge the power structures that determine artistic value.

This exhibition provides new perspectives on subjects that have been central to artists, including abstraction, popular culture, feminist and queer aesthetics, and recent explorations of identity and relationships to place. Together, the works demonstrate that craft-informed techniques of making carry their own kind of knowledge, one that is crucial to a more complete understanding of the history and potential of art”.

Making Knowing comprises more than 80 works in all media by more than 60 artists from the Whitney’s collection, including Robert Arneson, Ruth Asawa, Betty Woodman, Viola Frey, David Gilhooly, Eva Hesse, Mike Kelley, Liza Lou, Ree Morton, Howardena Pindell, Robert Rauschenberg, Elaine Reichek, and Lenore Tawney and Peter Voulkos, as well as featuring new acquisitions by Shan Goshorn, Kahlil Robert Irving, Simone Leigh, Jordan Nassar, and Erin Jane Nelson.

Some critics were confused by the cluster of the ceramics that had their own gallery, seeing as others were sprinkled throughout the show: Voulkos’ powerful Red River (c.1960); John De Fazio’s Crystal Meth Crucifix (1999), provocative as always; Mary Frank’s Swimmer (1978); and Charles Ledray’s Milk and Honey (1994-96) glass shelves displaying multitudes of tiny, white hand-thrown ceramic vases, bowls and pitchers––2,000 items to be exact.

A critic for Mousse Magazine Chris Murta commented:

“In the final gallery, the curators abruptly depart from their chronological format to single out one medium with a compact survey of ceramics, even though works in clay have been featured throughout. Though it includes some distinct pleasures—Viola Frey’s scale-defying businessman and the corporeal abstractions by Arlene Shechet and Katy Schimert, for example—this exhibition within an exhibition is a curious addendum. Yet it provides an alternative model for what the installation as a whole might have been. If the show had been organized trans-historically around themes, forms, and materials—as suggested above—it might have better illuminated the threads that connect disparate artists and movements through craft.”

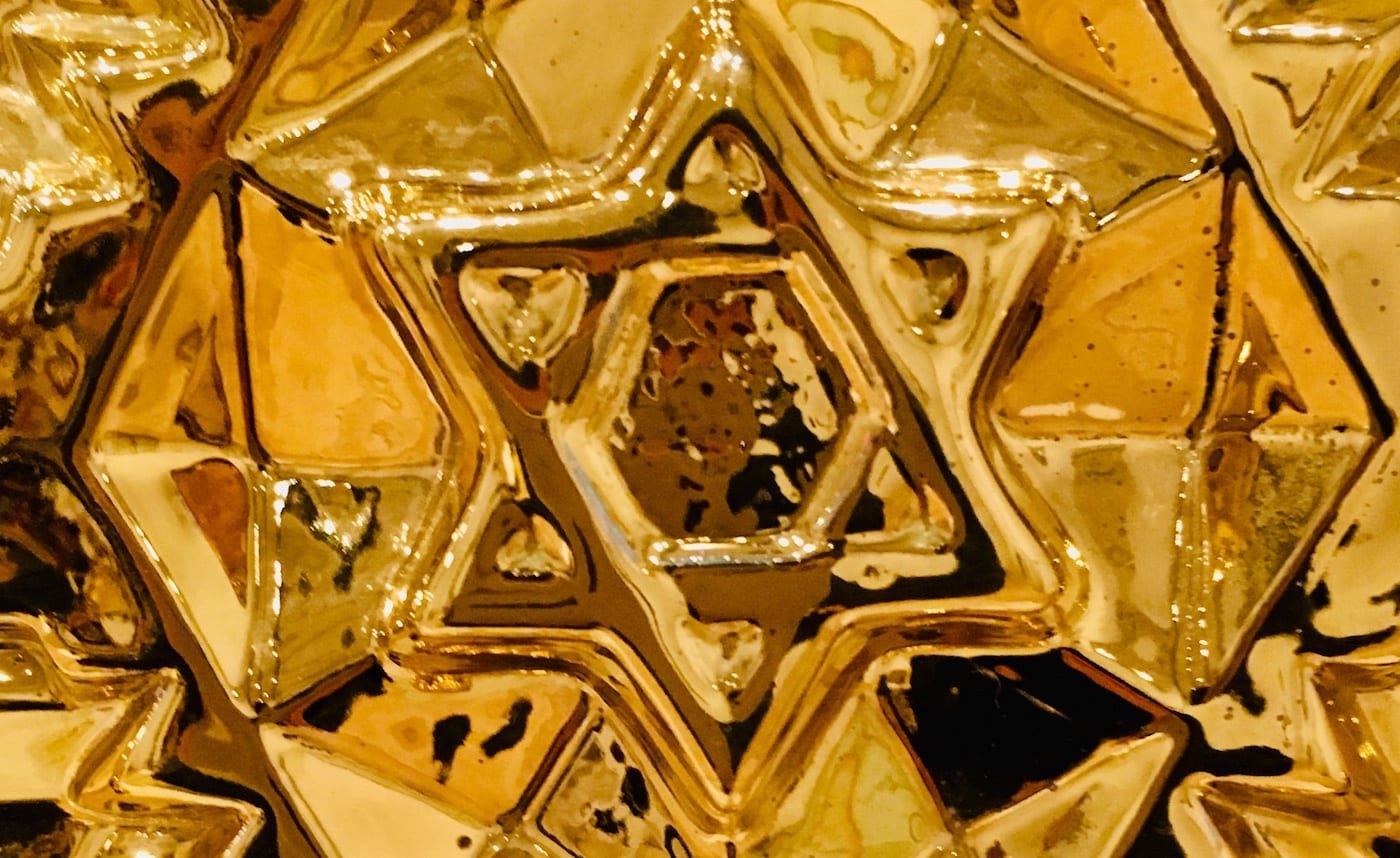

This mini-survey is a homage to the postwar ceramic movement––mostly in the Bay Area: Richard Shaw, Viola Frey, Ken Price, David Gilhooly, Robert Arneson, as well as Betty Woodman and Arlene Shecket. Bathed in light from corner windows, the richness of the glaze color can be seen at its best. Giving ceramics its own temple is long overdue is the beginning of reparations.

The Whitney’s ceramics tiered presentation was echoed at Miami’s #1 art fair (homage or accident), Art Basel, in the booth of Parker Gallery, Los Angeles, a space driven by missionary zeal, championing under-recognized artists with a special focus on Northern California art in the 1960s.

This too was an island, albeit more makeshift, which better fits the messy sensibility of Funk. This tasty taster showed a wider range of artists including Sandra Shannonhouse, Clayton Bailey and Chris Unterseher. For me, Robert Arneson’s Flip Flop (1978), Viola Frey’s quirky Untitled: Nude figures on Box with Bricks (1972) and Lightning Well (1970), and Rock Bottle (1971), by Richard Shaw were the three gems on the booth.

The ceramics world had worried that as more ceramics moved into the fine arts, its history would be lost. These two features at high-end venues, and others that we have covered, suggest that this may not be true and that clay’s fascinating timeline is slowly being integrated into mainstream visual arts. Also step by step we see Funk moving up the art tree. All good.

Love or loathe Garth Clark’s commentary on this exhibition from the world of contemporary ceramic art? Sound off in the comments section below.

I also agree with John Roloff.

I like to visit these museum!

Love it

One is struck with many of the ceramic installations of the dominate architecture of the plinth or sculpture stand as part of the visual field, which tends to limit how the object is understood and in some ways continues a particular, less conceptual, rendering of the “craft” language, which for me it is more of a problem than not. The works by Ledray, Frank and Frey, being larger (the assemblage by Ledray of small objects is larger by design), have another logic in their relationship to the viewer: floor or display apparatus, more in the direction of the artist considering that relationship. I have had this issue in the history of my own ceramic work as well. In many scholastic ceramic programs the class room is often filled with tables that most work is built upon, this fits well with electric kiln size, weight of object, height of viewing and collectability which seem to promote an problematic unconscious idea about the nature of a ceramic object, how it is conceptualized, made and too often given over to a default sculpture stand resolution for the viewer experience. If the table is a cafeteria table, perhaps that should be a clue to larger ideas or at least provoke interesting limitations. Ron Nagle’s recent show at the UC Berkeley art museum, albeit a solo show and with a decent budget, created an installation that highlighted the intimacy his work needs, in my opinion, for the viewer and his intent. In some ways this is changing with newer generations of ceramic artists, where a single pot-like object is understood for what that form suggests conceptually, or more complex works have the visual field and viewer experience in mind at some point in the process of making..

I absolutely agree with John Roloff.

The work surface in the ceramics studio, the average 32″ table top, is convenient, friendly yet tyrannical. A construction starts inevitably at the 32 mark and proceeds upward until the kiln dimensions are overlaid and size is determined at that moment of measurement. One thinks of John Mason, Stephen De Staebler and Jim Melchert in addition to Viola who worked with and around those constraints.

The table is a constraint that will not apply to everyone, often not an issue for wheel-making and function pottery which works to fulfill the scale of our domestic and cuisine ‘architecture’.