‘Do you know what a poem is, Esther?’

‘No, what?’ I would say.

‘A piece of dust.’

VIENNA––In times of personal struggle, pain or despair, we might mutter/whisper/whistle a verse of poetry or a tune of a song to ourselves. An image might flash up in front of our eyes, of a painting, a film, a sculpture we saw, which evoked emotions of comfort or companionship. What Plath describes is not to be understood as a counterpart to modern sciences. It is rather an alternative form of care, speaking to our psychological state rather than our physical one. Artistic practices can be strategies and means of political protest, forming alliances, helping to create and define the goals of communities. Their value lies in the variety of their carriers of meaning, their permeability and the possibility of an amplified intimate expression.

Ten small female figures besiege the Croy Nielson Gallery, Vienna in Birke Gorm’s exhibition titled Common Crazies (January 25 – March 7, 2020). Their torsos are made of a single terracotta brick, their limbs of terracotta pebbles found on the beach. The small jugs, cups and pots on their heads make them appear like a little army of pregnant fighters, jute cushions shaping their bulky bellies. They are equipped with remnants of shiny metallic beverage cans, champagne corks and nails, which they carry like shields and riot gear.

Contrary to the perception of pregnancy as a state of weakness that forces women into the domestic space, here, the pregnant belly is part of her combat equipment. The fighters are made from what is already there: things that were collected by Gorm over time. As reproductive beings they live in an economy of abundance instead of expediency; they are oriented towards giving instead of taking. Nevertheless, their approach to some kind of “origin” remains fictional: although the forms burnt from the red clay are reminiscent of primeval materials and objects, they are nowadays mass-produced goods.

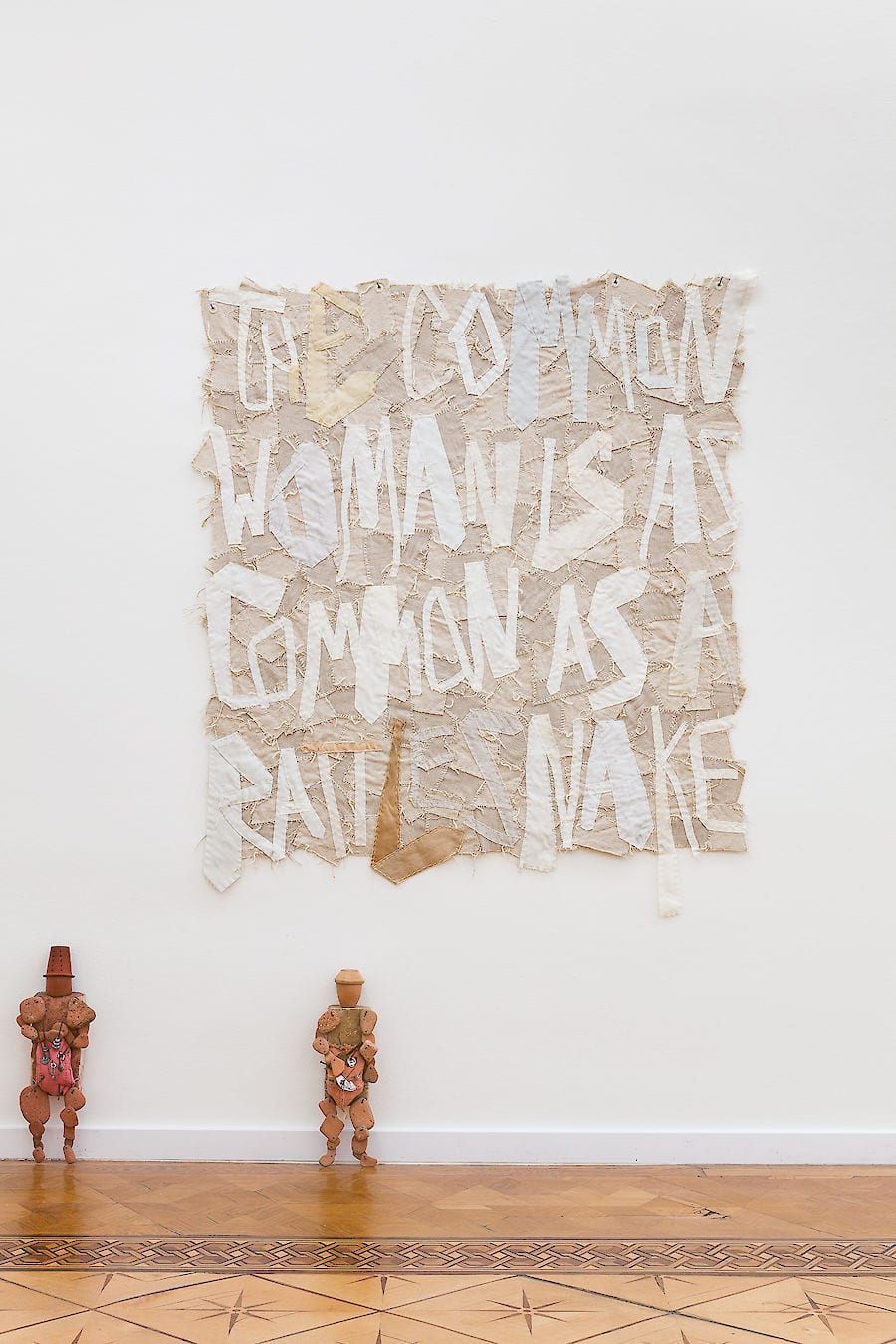

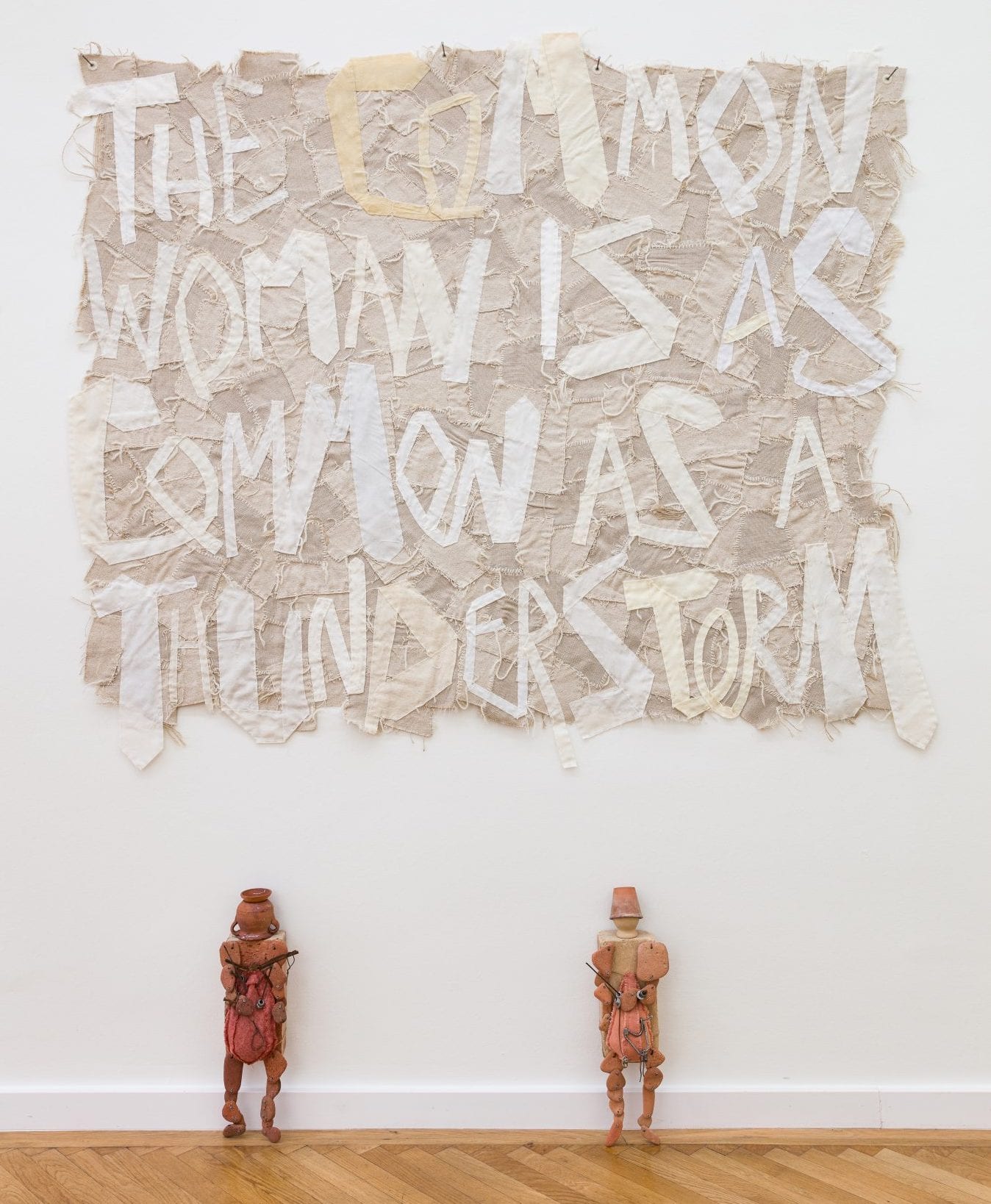

They are still wafting somewhere between an imagined natural or rough state (and thus an idea of origin), and a mechanized, highly efficient industry. Likewise, the collected metal waste on the one hand is part of the urban space, on the other, it’s carelessly thrown into the urban vicinity––foreign bodies in their surroundings. Five wall pieces made from burlap take up the symbolic attributions that poet and political activist Judy Grahn dedicates to the female protagonists in her “The Common Woman Poems” that were written in 1969. Tie linings are converted and appropriated as letters. The tie ‘skeletons’ are reminiscent of dusty relicts of an outdated symbol of power, of hierarchical order and male domination. The works are manufactured with the textile technique of crazy quilting, in which various scraps of fabric are joined together in coarse patches with highlighted seams.

Originally the quality of quilts depended on their sites of production: in rural areas, they were mostly featuring coarse, functional textiles such as burlap, whereas in cities more noble fabrics, i.e. leftovers from silk ties or blouses were available. The Common Woman Poems became a ‘coalitional voice’ for (gay) working class women in the U.S.: a voice, that combines personal with collective experience and reaches out to make alliances with other communities. Each poem portraits a specific character, but the ‘common woman’ can be any woman. ‘Common’ stands for ‘ordinary’, but also for ‘mutual/together’, and it is this sense of togetherness/commonality for which Grahn provides a voice.

—Text from Gallery Press Release written by Inga Charlotte Thiele

Love or loathe this exhibition from the world of contemporary ceramic art and contemporary ceramics? Sound off in the comments section below.

Add your valued opinion to this post.