NEW YORK — Italian artist Marisa Merz’s (b. 1926) exhibition The Sky is a Great Space at The Met Breuer (January 24 – May 7, 2017) explores her prodigious talent and influence. It is the first major retrospective survey encompassing five decades of the artist’s work tracing her early experiments in nontraditional art materials to her intricate installations to her enigmatic ceramic heads.

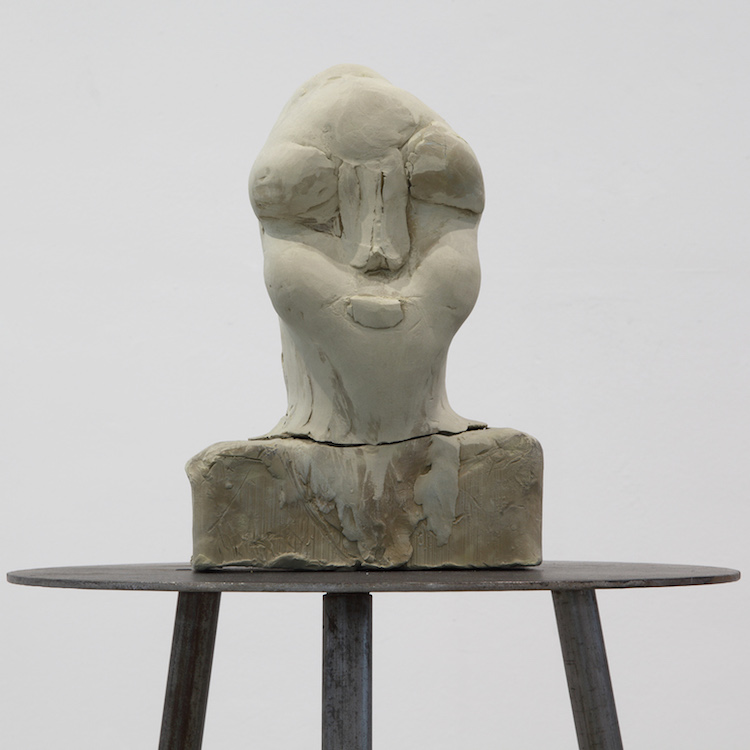

Above image: Marisa Merz, Teste, Image courtesy the artist, Fondazione Merz, and Archivio Merz. Photo by Renato Ghiazza

Rejecting categorization and even history, leaving some of her work undated, Merz opted to forgo traditional gallery space (a symbol of material wealth), instead, practicing art-as-life using her home as her studio, and even transforming it into an exhibition space, Hyperallergic writes.

Instead of espousing the life-as-art practice endemic to art movements of the 1960s like Fluxus and Happenings, Merz’s Living Sculptures are more art-as-life: works so beguiling and domineering that, when installed in her small Turin kitchen, they subsumed her lived space into her art.

Marisa Merz, Untitled, (undated), Graphite and lipstick on canvas, 19 11/16 x 15 3/4 inches. Image courtesy the artist, Fondazione Merz, and Archivio Merz. Photo by Renato Ghiazza

Marisa Merz, Teste heads, Image courtesy the artist, Fondazione Merz, and Archivio Merz. Photo by Renato Ghiazza. Click for larger image

Merz’s later work explores feminine sexual and cultural identity investigating through the kinesthetic experience of art creation. The Merz Foundation writes:

Marisa Merz has distinguished itself in time for a personal path, developed into an autonomous and independent manner. [Her] research makes use of more and different media ranging from drawing to sculpture, from painting. Insisting on the importance of manual skills of art making, recovers its technical craftsmanship women, such as sewing and weaving.

According to Hyperallergic, her drawings, sculptures and especially so in her ceramic Teste series which features seemingly face-less heads staring into a state of suspended time rendered with plastic, unfired clay and copper wire, remaining true to Arte Povera’s aesthetic.

In fact, this series of haunting, identity-less faces seems to capture the anti-humanist turn of postwar art with a primal elegance unique to Merz. Their cryptic articulations in wax, ink, and chalk teeter on the edge of humanizing their subject: they could be anyone, or no one at all. The pleasure is in the mystery.

Merz proves that domesticity — and for that matter, the female experience — is no light fodder for art; rather, she uses it deftly to radically critique many of the same phenomena as the rest of the poveristi, but to a piercing and multifaceted effect.

Marisa Merz, Teste heads, Image courtesy the artist, Fondazione Merz, and Archivio Merz. Photo by Renato Ghiazza. Click for larger image

Merz’s recognition as an artist in her own right is long overdue, Hyperalleric writes.

[The Sky is a Great Place] rightly asserts Merz’s place in art history far beyond the bounds of Arte Povera.

Merz was the sole female protagonist (and married to a key member) of the Arte Povera movement; the most significant and influential avant-garde movement to emerge in Europe in the 1960s, characterized by its use of simple, accessible materials such as rock, rope, paper, dirt and clothing.

As members of the poveristi, the artists that comprised Arte Povera forged an artistic rebellion against the sudden economic boom of the late 1950s and early ’60s in Italy, and its quickly expanded middle class, through their use of dejected and unconventional materials.

Even so, Merz was not always included the movement’s first exhibitions in the late 1960s and early ’70s — a marginalization that can been seen seen throughout her oeuvre, The New York Times writes.

The difference is that Ms. Merz’s work is actually better than her husband’s…Arte Povera may turn out to dwell largely in Ms. Merz’s shadow.

Marisa Merz, Teste heads, Image courtesy the artist, Fondazione Merz, and Archivio Merz. Photo by Renato Ghiazza. Click for larger image

The exhibition featuring more than 100 works is organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The show heads to the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles on June 4. The exhibition and publication were developed in close collaboration with Fondazione Merz, Turin.

Do you love or loathe these works from the worlds of contemporary ceramics and contemporary art? Share your thoughts on Merz’s work in the comments.

Add your valued opinion to this post.