It’s hard to escape the nagging fear that doomsday is right around the corner. I suppose every generation wonders whether they’re the final one (scientists during the Cold War even gave us a handy clock that tracks our progress toward Armageddon) but the sense that destruction is at hand and inevitable feels ubiquitous today. We all have a friend who brightens up our Facebook news feeds with stories about mass fish extinctions, or California running out of water within a year. Popular culture mirrors this with films about people living in dystopian wastelands; every other video game that gets released features hordes of zombies shuffling around dead and dying cities.

The fear is difficult to handle. You feel negligent to ignore it and move on with your life, but at the same time the problems are large enough to be demoralizing. Existential threats have an attendant fear: that you as an individual lack the agency required to overcome the threat. The whole ugly mess cries out for some kind of catharsis.

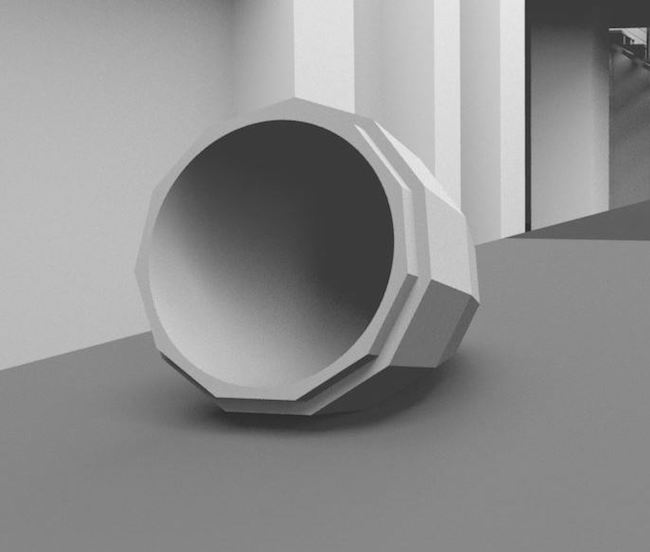

In 2012 (which, if you remember, was supposed to be the end of the world per an ancient prophecy) Polish artist Marek Cecula addressed that need for catharsis with Seeds, an exhibit at the BWA Wroclaw, Poland. The project has aspects of futurism, which appeals to my sci-fi nerd sensibilities and my bittersweet hope that humanity will do better on the second go-round, assuming we get the chance. The gallery states that Cecula designed forty “seed” pods, airtight ceramic containers that hold materials and tools that post-collapse people could use to rebuild. Symbolically, these were dispersed across the planet, like time capsules, for use if people ever need them. From the gallery:

“There is no space left for any valuable objects representing our culture or development of civilisation, there are no technological gizmos. Cecuła refers to the sources of life, only intending to preserve the existence of live matter which would allow an evolutionary revival of the civilisation. The exhibition presents twenty large and twenty small “seeds”. Each is composed of two airtight elements. In its final version, the project is planned to contain a hundred such forms to be distributed all over the planet in order to secure the ultimate survival. The design of the “seeds”, their aesthetic form, is supposed to evoke a sense of security and hope for Rebirth.”

The pods were supported in the exhibition with information about natural disasters and materials from those disasters. As I wrote earlier, the temptation when one is confronted by an existential threat is to look the other way; if you can’t address the rouge asteroid hurtling through space on a collision course with Earth, why bother acknowledging it? Cecula denied his audience this cop-out by confronting them with information about the threat; more than that, Cecula coupled this information with artifacts from those disasters, he showed rather than told and so looking the other way became almost impossible. That created a sense of rising tension, putting the audience in the right frame of mind for catharsis in the form of his seeds.

It would have been interesting to poll people who attended to find whether they may have gone through the five stages of grief during the exhibition: starting at denial and arriving at acceptance. But beyond mere acceptance of loss, there’s a benevolence in the pods that seems to say that if you can’t save yourself, you can at least give the people who come after you a better chance of survival. Cecula’s project is like the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, but for your soul.

Now, I’m not a nihilist (confession: that’s probably a lie), but the design of the pods, perhaps unintentionally, subverts what would otherwise be an auspicious message. To be frank, they look like torpedoes (this realization came to me in the video below when I saw them lined up on metal racks looking like something from a munitions depot). Their design could be the exhibit’s sci-fi futurism at work, but the association is still uncomfortable. Assuming things do play out in the worst possible way and that humans found these pods, what does that imply? Our civilization is in its current state of affairs because of our own actions. We wouldn’t have the need for catharsis if we weren’t suicidal in our drive to choke the atmosphere with carbon dioxide. There wouldn’t be the threat of nuclear annihilation if our governments weren’t engaged in a juvenile pissing contest with other world powers.

The pod’s design, its message, unintentional though it may be, is that humanity will carry its self-destructive tendencies into the future. Yes, we could rebuild, fix things on the next try, but that’s not going to erase the inner malfunction that brought us to the brink of extinction in the first place.

Best to ignore that thought.

Bill Rodgers is a Contributing Editor at CFile.

Any thoughts about this post? Share yours in the comment box below.

Add your valued opinion to this post.