PITTSBURGH, Pennsylvania — The following is critic Anthony E. Stellaccio’s review of the Edward Eberle Retrospective at the Society for Contemporary Craft, currently on view (Pittsburgh, Sept. 9, 2016 – March 11, 2017).

In as much as a retrospective exhibition is about an individual’s accomplishments in art over a lifetime, so is it also about the individual and the life lived. And perhaps it is in the examination of the latter where success and value diverge. These are Einstein’s words, or at least a version of them, that I am reminded of in surveying Edward Eberle’s current retrospective.

Eberle (pronounced EbbRrLy, born 1944), whose work appears in private and major collections throughout the country, has been a commercial and critical success. Conversely, Eberle has not been a celebrity in the often showy, competitive, persona-fueled artworld. Instead, Eberle has remained rather reclusive, concerning himself with regular studio hours, the diligent pursuit of technical and aesthetic perfection, and the questions with which he grapples in his work. Similarly, this seasoned and respected artist has remained loyal to his roots in western Pennsylvania, having lived and worked there all of his life.

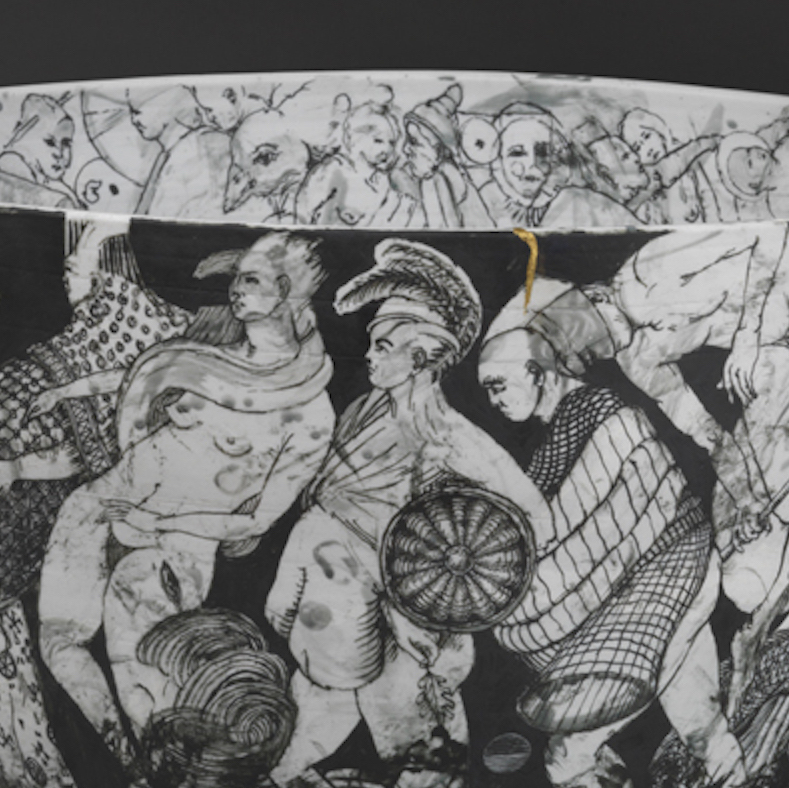

Edward Eberle, Under the Influence of the Moon, 2013, porcelain and terra sigillata, 26 1/4 x 13 1/2 x 13 1/4 inches

As much a local institution as a local inspiration with an impeccable national and international resume, Eberle has rightly become one of the few artists to be given a solo exhibition at the Society for Contemporary Craft (SCC) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This retrospective is complemented by a nearby exhibition at The Bank of New York Mellon Center featuring four other artists: Ian Thomas, Erica Nickol, Jonathan Schwarz, and Jeff Schwarz. There is also a case at Eberle’s retrospective containing one example of work from each of these artists. All of them originally from western Pennsylvania and all dramatically and directly influenced by Eberle, the presence of these four artists is part of what defines their mentor as something of a local, living legend. More succinctly, the show as a whole is a testament to this master’s value, dedication, generosity and integrity.

Naturally, there is a story in the work as well, which at SCC progresses across three decades: from the more minimal decoration of conventional vessel forms in the 1980s to the mixed media sculptures of late. This is not to say, however, that Eberle’s evolution has been either entirely linear or compartmentalized. Indeed, part of what makes this retrospective interesting is how consciously its subject learns from his past works and how the cycle of ideas is exhibited, both in his works and in show.

Although all the surveyed art of this discriminating maker is superlative – aesthetically sound and reflective of his high technical standards and conceptual vision – perhaps most compelling are the altered and highly illustrated vessels begun in the 1990s. While the shadows of classical Greek pottery, funerary forms, and imagery that are infused in these “vessels” are unmistakable, they are also decidedly contemporary. And between these two chronological polarities the works also seamlessly blend traces of medieval alchemy and the shamanism of stream-of-consciousness, beatnik poetry. The works are expert and ethereal. Yet what really stands out beyond these more obvious observations is the palpable and paradoxical vulnerability of Eberle’s work.

Edward Eberle, Chest, 1993, porcelain and terra sigillata, 18 x 11 1/2 x 11 1/2 inches. Click to see a larger image.

Edward Eberle, Whiplash II Revised, 2005, porcelain 25 x 17 x 16 inches. Click to see a larger image.

In the construction of his art, this consummate creator is known for pushing porcelain to its limits, creating large forms of incredible thinness. Even in increasingly complex, sculptural vessels, for which thickness as a convention might be more acceptable, Eberle has retained a signature delicacy. These forms, reduced in mass to an almost ephemeral state, are then attentively illustrated, in a state of great concentration over weeks and months, with black terra sigillata. One mark is put down and carefully considered before another mark is put down and the canvas of porcelain is gradually filled with suggestive and interrelated imagery that is, alternatively, non-linear if not completely non-narrative. The physicality of the work (or more correctly its absence) and sensitivity of the drawing process, carried out before the pieces are once-fired to cone 10, display the confident and high-risk vulnerability of the work and the artist. As Eberle embraced cracks and tears, and in his mid- and late-career deconstructed his own aesthetic formulas, the artist’s ability and vulnerability were increasingly laid bare.

In the same vein, a rather curious note is sounded in a short YouTube video (constituting a substantial part of Eberle’s modest media presence, in which the artist describes the beginning of the drawing process as a “spoiling of the canvas.” This so-called spoiling is an initiation, meant to free the artist from his fears and inhibitions as he approaches the “blank field” of the canvas without a well-schematized plan. Though it is a phrase innocuous enough as artspeak, Eberle’s demeanor and the seriousness of his enterprise allows him to convey a sincerity that asserts there is real fear, even regret, and a thoughtful, self-aware vulnerability mixed in with the precision, drive, and power that create, and ultimately emanate from, his works of art. And at the core of all of this is a truly great respect for and rapport with his material. This is but one example of how it is not only the tangible, physical presence of the work that makes it compelling and defines Eberle’s legacy: it is also the intangible, almost quivering poetry contained within the thin, delicate membranes of his creations.

Review by Anthony E. Stellaccio.

Do you love or loathe these works of contemporary ceramic art? Let us know in the comments.

The most inspirational article I’ve seen on CFile