We’ve decided to offer up one last serving of our Exhibition Digest to cap off the year. These stories of ceramics exhibitions from around the globe were just too tasty for us to keep to ourselves. Enjoy!

Allan McCollum | Why Pots without Clay?

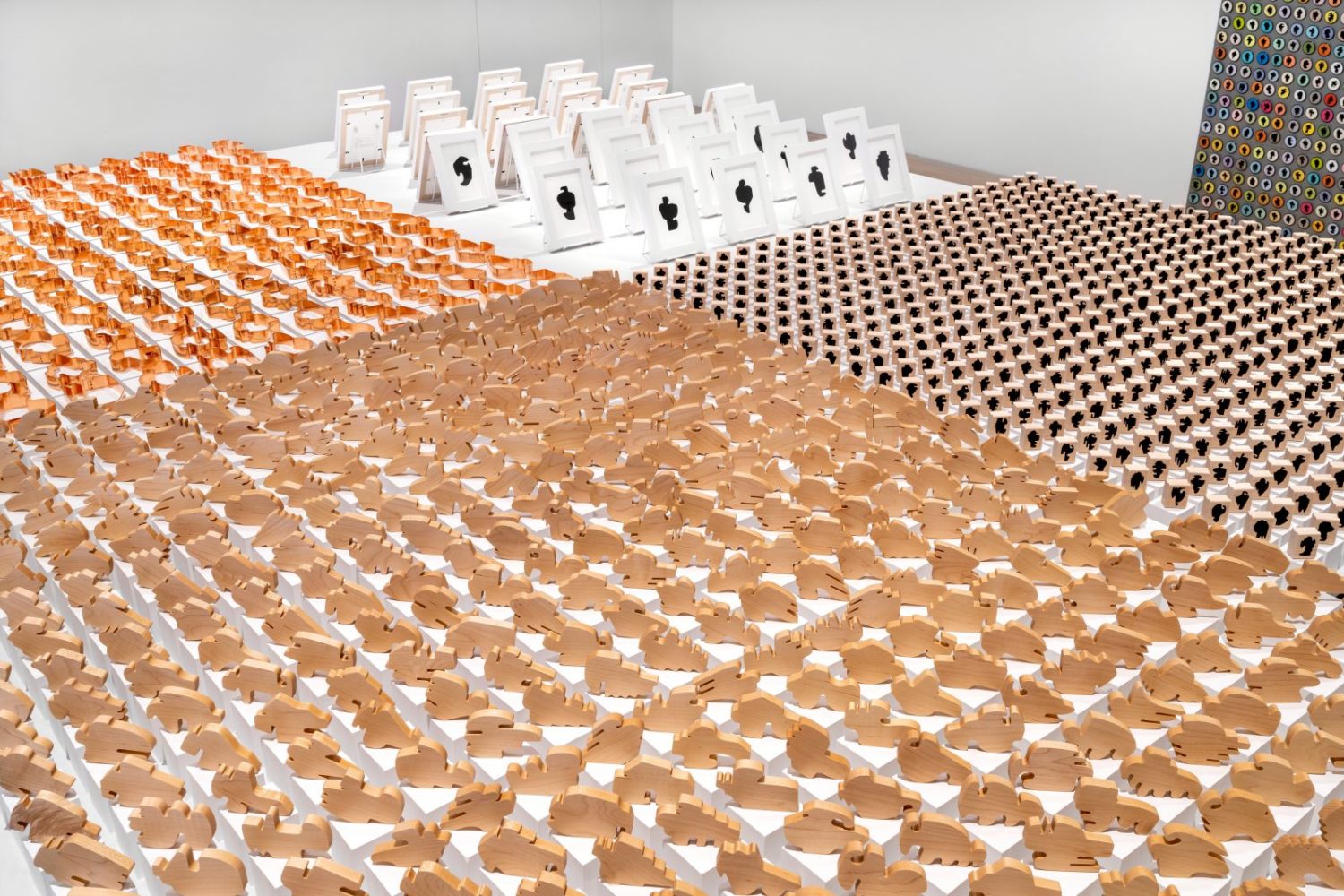

The Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA Miami) first U.S. museum retrospective for legendary American artist Allan McCollum (b. 1944) that opened on March 26, 2020, Allan McCollum: Works Since 1969 traces the artist’s iconoclastic philosophy on the originality, value, and context of art. This falls into our “Not Clay But…” stream.

It has always stuck us that McCollum with his Perfect Vehicle series since 1985, a stylized Chinese ginger jar, and plaster works that look exactly like either unfired or bisque wares, has never worked with clay even though he did ceramics at school. Actually, there was some ceramic work early on but the absence thereafter had to do with family.

In his interview for Archives of American Art McCollum notes that, “My mother, my father, my aunt, all worked at a ceramics factory called Metlox Pottery in Redondo Beach—Manhattan Beach—Southern California, making mass-produced objects”. That explained everything. His way to accept his family’s influence and yet distance himself, was to change material.

“By rethinking modes of artistic production and distribution as parts of larger economies of value, McCollum is one of the most influential American artists working today,” said Associate Curator Stephanie Seidel. “Over more than five decades his work has remained timely and effective at challenging aesthetic and material concerns, while critically reflecting on the museum context.”

Alfonso Leoni’s Innovation honoured by MIC

Alfonso Leoni was born in 1941 in the ceramic town of Faenza, Italy, and died from leukaemia at the age of 39. Like many of Italy’s leading post-War ceramists, his life was closely linked to his hometown, where he studied at the Art Institute Ballardini, and taught sculpture from 1961. This dynamic artist is celebrated in a large exhibition, curated by Claudia Casali, director of the MIC, the Museum of International Ceramics, Faenza (October 1, 2020 – June 13, 2021).

As Marta Leoni writes:

He had a love and hate relationship with Faenza. He tapped a great amount of energy from this town, but at the same time it limited his possibilities. He relentlessly continued his research into new experiences and different art languages. This led him away from Faenza, while inextricably linked to the ceramic tradition. He started using different materials (paper, wood, bronze, plastic, marble, iron and precious metals, glass), cutting, ripping, assembling, destroying them, he involved his body, looked for impossible and unthinkable solutions, often stumbled upon by chance.

In the last ten years of his life he came into contact with design. He was fascinated by the possibility of spreading his projects and provocative ideas to a wide audience. German manufacturers Villeroy & Boch and Rosenthal, immediately recognized his talent, providing him with ateliers and assistants to realize his innovative ideas.

Leoni’s exhibition is a reminder that Western ceramics has undervalued, even ignored, the innovative role that Italy modern ceramics has played, work that is often much more liberated, sophisticated and closely aligned with the fine arts than most of Europe, which was somewhat bogged down in tradition. Time to update text books.

Photographs courtesy of MIC.

Shozo Michikawa | Totemic Ceramics Paired with Lush Photographs

London–Erskine Hall & Coe presents its fifth exhibition of the productive ceramist Shozo Michikawa, born in Hokkaido, the most northern area of Japan, in 1953. He showed with the photography of Yoshinori Seguchi. He has shown internationally but perhaps the most meaningful was when he was invited to launch an exhibition in the forbidden City Beijing.

He does not come from a pottery legacy going back generations, indeed he first learned ceramics from evening classes. However, he was fortunate to find a muse; “Tozaburo Kato who is a 34th-generation potter – her family have been making pots in Seto for nearly 1,000 years”. Since then, he has become one of the most respected ceramists, known now for his powerful architectonic totems assembled with vigor and intuition. In the catalogue for the Forbidden City exhibition, he comments:

The energy of nature is truly immense. No matter how much our sciences and civilisation might evolve, the power of human beings is inconsequential in the face of natural threats such as typhoons, earthquakes, tsunamis, and erupting volcanoes. [– that environment was a big influence on my pottery. I lived by a lake in a beautiful national park beside Mount Usu. Nature there is full of power. When I was in my mid-20s there was a big volcanic eruption, which I witnessed. I think I gained something from that energy.

I think this is why the works created by the natural world, for example, the patterns formed by the winds on the desert sands, or a majestic cliff overlooking the ocean, contain a power that can never be imitated by human hands. My own creative activities have been inspired by various phenomena in the natural world; even those that can be seen in everyday life.

Shozo Michikawa

Daisuke Iguchi Delivers Structured Bliss

The Pierre-Marie Giraud Gallery in Brussels has hosted a handsome show of ceramics by Daisuke Iguchi. Born in 1975 in Tochigi, he studied ceramics at the Tohoku University of Arts and Design in Yamagata and at the Mashiko Pottery Institute in Tochigithen. Then he entered five years of apprenticeship in the atelier of artist Masayuki Uraguchi. In 2004 Iguchi set up his own studio. Drawing inspiration from his respect and admiration for his predecessors, the Yayoi Japanese potters, and from the landscape surrounding him, Iguchi exclusively sources his clay locally. As Giraud explains:

From a childhood spent in the countryside, Iguchi retained a fascination for moss covered stones, rusted metal and patinated objects. To encapsulate these properties in his artistic practice, Iguchi undertook a lengthy empirical research to find a balance in combining soil, water, rice ashes, metal, fire and time.

The artworks of Iguchi have a skin. Rich and textured, sometimes looking like carved stones, sometimes like chiseled metal, the works are rarely identifiable, in the first-time place, as ceramic, vessels made of smooth curves and interlocking volumes, that are both technically challenging and visually unsettling. His elegant and ample shapes have a regular nature, yet are not symmetrical, suggesting no preferable angle from which to look at them. These artworks grow and take form between the hands of the artist with no preliminary drawing.

Add your valued opinion to this post.