This exhibition at the Honolulu Museum of Art (Honoulu, January 31-April 27, 2014) by Diane KW (Diane Chen) had its genesis on December 18, 1751 when The Geldermalsen, a Dutch East India Company ship, left the port of Canton, China, for the Netherlands. On board was a crew of 112 men, 700,000 pounds of tea and 203 chests holding 240,000 pieces of Chinese blue and white porcelain, as well as silk cloth, exotic woods, lacquer and gold bars.

As the museum explains in its contextual material:

“While passing through the Bangka Strait, which separates the islands of Sumatra and Bangka in the Java Sea, the Geldermalsen struck a reef on the evening of January 3, 1752, capsized and sank with 80 men, including the captain, Jan Diederik Morel, and the entire cargo. The tea and the gold were the most valuable goods; the porcelains, although headed for market, functioned mainly as ballast to stabilize the ship. An investigation was conducted, with many of the survivors being questioned.”

The documents relating the story of the Geldermalsen’s fate would remain untouched in the Dutch East India Company’s archives for almost 235 years but for Michael Hatcher, a marine salvager:

“In 1985 [he] located the wreck and from 1985 to 1986 his operation retrieved 150,000 undamaged porcelains that he shipped to Christie’s in Amsterdam for auction. Seeing the porcelains in Christie’s warehouse, Christiaan Jörg, then curator of the Groninger Museum in the Netherlands, was able to verify that the pieces came from the Geldermalsen, intensifying media coverage of what Christie’s had dubbed the ‘Nanking Cargo.’ The auction brought more than 40 million Dutch guilders (approximately $20 million), creating a sensation in the art and auction world and also sparking outrage from the Indonesian government, which claimed the wreck was in its territorial waters, as well as from maritime historians and archaeologists, who deplored that the wreck had not been studied more thoroughly and unique data had been destroyed.”

Jörg requested and received all the shards and damaged works shards for the Groninger Museum. Jörg heard about Diane KW working with porcelain shards and gave her pieces to create “new” works of art, applying digital ceramic transfers of original texts, engravings and modern auction photographs that trace the story of the Geldermalsen.

The result is At World’s End—The Story of a Shipwreck: Works by Diane KW first shown at the Groninger and now in Honolulu. Shard art is a crowded genre in ceramics but KW’s work sets a new standard for beauty, concept, context and history. She blends it all into a distinctly contemporary installation. What gives particular grace to these works is the ordered but hypnotic penmanship, calligraphic art in its own right, which is evident in the documents she copied and applied form the Dutch East India Company’s archives.

As KW explains:

“While the Groninger Museum is a contemporary art museum, it also has a large excellent historical collection of antique ceramics from the 18th and 19th centuries,” says Diane KW. “The Geldermalsen shipwreck shards the museum had were clearly a part of the history of China, the Netherlands, and Europe. It seemed to me that the shards should move forward in time to become contemporary art, but without loss of their historical context. So I decided to tell their story in a contemporary way.”

The setting could not have been more perfect. When the new Groninger was built Philippe Starck was tapped to completely reinvent the way in which a blue and white porcelain gallery could be shown. His signature diaphanous curtains symboled the purity of porcelain, certain works could be viewed through a ship’s telescope and in the floor was a pool covered in glass with the shards from the Nanking cargo wreck scattered amongst rocks and coral with with live fish!

KW’s statement for the exhibition touches on the mystery and poetics that inspired her.

“Most of us try to stay near the ocean’s surface where water, air, and light meet, but there are the brave ones who would dive deep to discover hidden secrets below. There are so many secrets at the bottom – strange-looking sea creatures, shipwrecks, sunken treasure.

“I am a ceramic artist, and for me the sunken treasure is not gold or jewels, but rather ancient ceramics salvaged from the ocean’s depths. These vessels have become shards, their asymmetric individualities hinting at their histories. I help ceramic shards tell their stories, stories about the history of man, his accomplishments and his failures.

There is another genesis to this body of work:

“At a dinner party I met Bill Sargent, former Curator of Asian Export Art at the Peabody Essex Museum. I told him of my idea to combine ancient pottery shards with spam emails. Bill said he had a shard collection that he would give me for experimentation. The first shard he gave me was a Ming Dynasty stemmed cup shard. The end result was wonderful—we both loved it and Bill took it back to China, to donate it to the Nanchang Ceramic Museum for their permanent collection.”

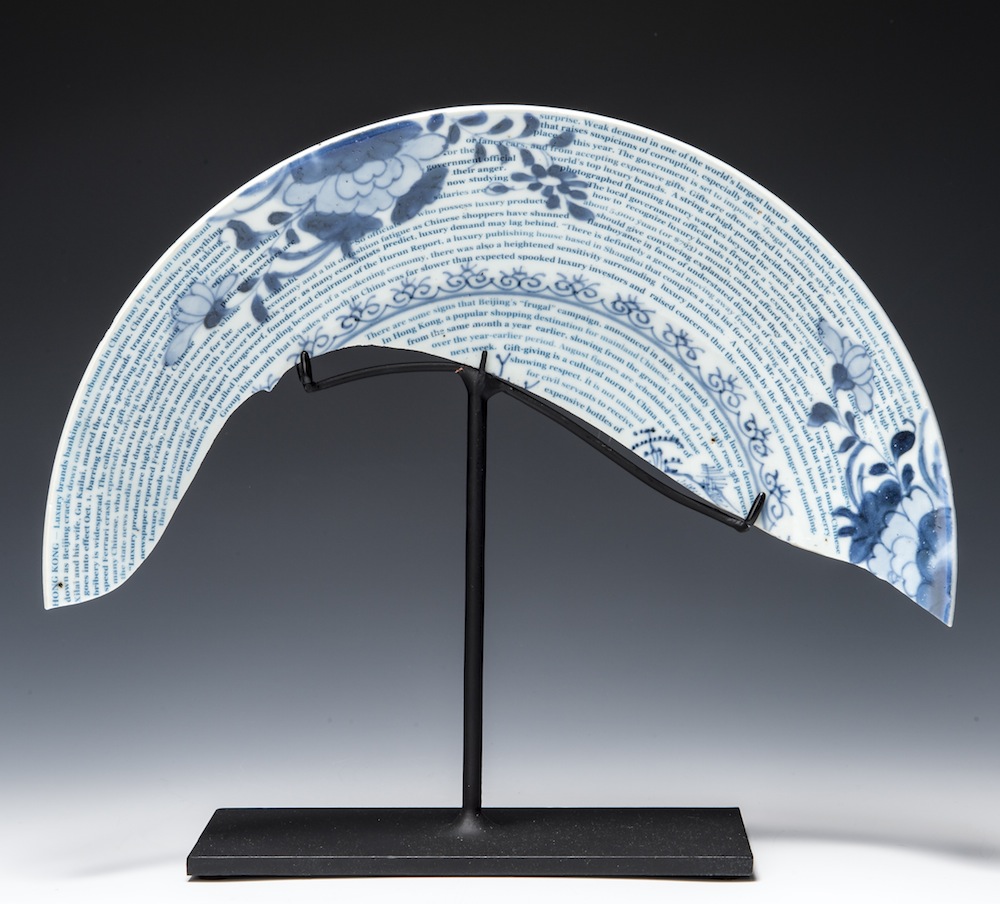

You can see the cup illustrated in the interview between Leza Griffith and KW that is also part of this issue of CFile. KW is working with extant material for the greater part but she adds contemporary contributions. For instance The Price of Doing Business (above) is a comment on Modern-day China’s old world methods of doing business and giving luxury items to government officials. According to a recent Reuters News Agency account the Chinese government’s attempts to halt this are having little success. KW sees this as “a continuum over time, this shard and the news report link the past and the present trade practices, questioning the likelihood of government officials policing themselves.”

Her gift for collage is quite magical and the work’s language and imagery against the original cobalt decoration by China’s gifted artisans from centuries ago raise complex, myriad issues: mercantile history, East-West politics, power, wealth, ceramic history and even deep pathos that is stated with mournful simplicity in the work, They Were only Boys..

Exhibitions of this quality and content define the notion of a ceramic art, an independent genre that has relevance by the richness of this material’s culture. Not all ceramics seek this place in art but when they do the payoff for ceramophiles is substantial.

Garth Clark is Chief Editor of CFile.

Above: Diane KW, The Price of Doing Business, 2013. Collection of the Groninger Museum. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

Diane KW, The Geldermalsen Triptych: The Harvest, The Catastrophe, The Politics. Collection of the Groninger Museum.The large basin shards in this triptych work recount their history from the order and production of decorated porcelain pieces (The Harvest), to the shipwreck (The Catastrophe) and loss of the porcelain, to the storm of controversy after the sale of the salvaged pieces (The Politics).

The Harvest: On back: Engraving of merchants weighing blocks of tea. Photographic images of Batavian cups and saucers and inventory texts have been applied. The term “Batavian” is used for porcelain dishware that has been glazed brown on the outside.

The Catastrophe: Accounts of the Geldermalsen shipwreck and images of fish and sunken porcelain everywhere speak to the loss of cargo. A fleet of merchant ships and an account of the shipwreck symbolize the hazards of commerce in the 18th century.

The Politics: Serendipitously broken into two main shards, this large basin recounts the political controversy surrounding the salvage of the Geldermalsen. On the left are quotes from those who objected to Hatcher’s activities and on the right, Hatcher’s position and those who were more supportive of his position regarding salvage. Although much of the objection by the academics and governments was related to the plunder of an archaeological site without adequate preservation, there were strident objections to Hatcher profiting financially as well. Christie’s and collectors were condemned. Indonesian and Chinese governments felt they had claims to the profits.

Diane KW, Help Wanted: Dishwasher, 2013. Collection of the Groninger Museum.The front of this plate shard shows pages from the inventory ledgers as well as images of porcelain teapots recovered from the shipwreck. The Geldermalsen carried approximately 250,000 pieces of porcelain onboard. Of these, 150,000 intact pieces were recovered. On the back of this plate are images of rows and stacks of salvaged dishes as they were photographed prior to Christie’s auction.

Diane KW, Bentleys Not Opium, 2013.A 2012 newscast reporting China to be the second-largest importer of Bentleys in the world has been added to this shard. No longer the number one importer of opium, China has become wealthy through hard work and low wages. As a consequence, the nation has become very rich. On back: An image of merchants weighing bricks of tea has been altered to be weighing a Bentley. A continuous stream of porcelain cups and saucers merges into the weighing, and emerges from the image as Bentleys with porcelain wheels.

Diane KW, Requiem for the Geldermalsen II, 2013.The VOC (Dutch India Company) appeared to be more concerned about the lost gold than the lost lives after the shipwreck. Names of some of the crew members who died and the positions they held onboard have been transferred to both shards. On the front surfaces the names are faded, almost lost amidst the superimposed currency and commodity symbols.

Diane KW, The Ballad of 1752, 2013.The poet sits in his house in China under the trees full of dishes to be harvested. He has just heard of a shipwreck laden with tea and porcelain. He reflects on all the porcelain, now lost at the bottom of the ocean, but knows there will be a new harvest soon. He hears the ballad of the dishes. The Dutch version of The Ballad of 1752 with stacks of dishes recovered from the Geldermalsen have been added to the back of the shard.

The Ballad of 1752

We were destined for distant shores and fine tables,

To be held and used,

Treasured by elegant fingers and kissed by ruby lips.

But Fate intervened,

Leaving us broken and shattered,

At world’s end.

But we have stories to tell!

So many stories to tell . . .

Diane KW, They Were Only Boys, 2013. Collection of the Groninger Museum.Four boys under the age of 15 were aboard the Geldermalsen, as trainees serving the officers. One of the four was Captain Morel’s son. All perished when the ship sank. This small shard, bearing the names of the boys, remembers them forever.

Installation views, Groninger Museum, Groningen, July 15-Sept 15, 2013.

Installation photos of At World’s End at the Honolulu Museum of Art (January 31 – April 27, 2014). All photographs courtesy of the artist.

Visit the Honolulu Museum of Art

Visit CFile Shop to see an exclusive series produced by Diane KW for CFile Foundation

Provocative and beautiful. Brilliant!