The summer of 2015 was a big one for Chinese artist Ai Weiwei. In addition to the government returning his passport after extra-judiciously confiscating it in 2011, Ai held his first solo exhibition in his home country. That signaled an end for one of the strangest quirks about the artist: his work was devoured abroad while he was treated with utmost suspicion at home. In June, Ai held a show between two galleries in Beijing, Galleria Continua and the Tang Contemporary Art Center. Weiwei also has a solo exhibition, still ongoing at the Royal Academy of Arts, London (September 19 – December 13).

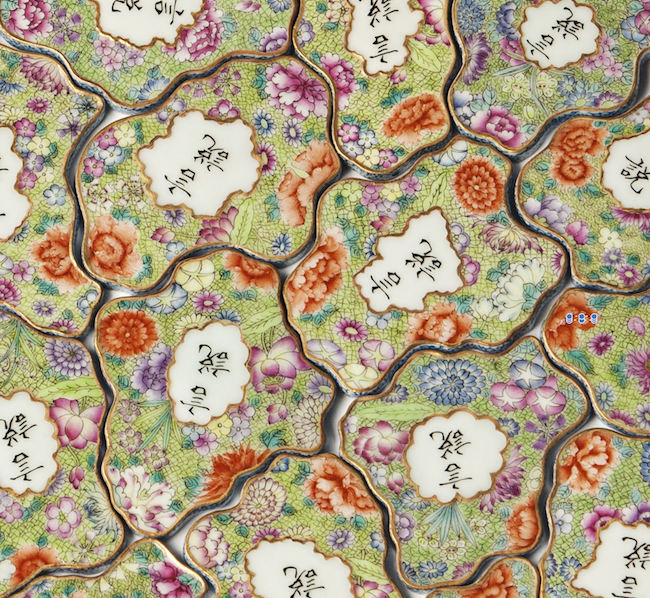

Ai Weiwei, Free Speech Puzzle, 2014. From D-Talks: The slogan ‘Free Speech’ decorates each of the individual porcelain ornaments that collectively form a map of China. Ai has produced numerous Map works in disparate materials, such as wood, milk powder cans and cotton, over the past twenty years. The components of Free Speech Puzzle are based on traditional pendants made of various materials such as wood, porcelain or jade, depending on the wealth of the individual, that bore a family’s name and served as a marker of status and as a good- luck charm for the wearer. Through the multiple pieces Ai creates a rallying cry that reflects the distinct geographic and ethnic regions that together form modern China and which, despite their differences, ought to have the right to free speech as their principal common denominator.

The way the New York Times tells it, the exhibitions in China played out as you might imagine them. People lined up for pictures and selfies with the artist. Government censors were breathing down his neck, demanding approval over everything before it was put on display. The Times goes as far to say that Ai didn’t use any of his firebrand political commentary in the show.

Instead, Mr. Ai has chosen to take a more subtle approach. At the center of the exhibit, which was mounted with prior approval by the local authorities, is a 400-year-old Ming dynasty-era ancestral hall that Mr. Ai and his team disassembled and rebuilt in two different exhibition spaces, splitting the monumental wooden structure between the Galleria Continua and the adjacent Tang Contemporary Art Center. The process was documented in video and photographs that are also on display.

Visitors gather around one half of a reassembled ancestral hall at Ai Weiwei’s exhibition in Beijing.

“Subtle” with regard to Ai’s tone shouldn’t be confused with “absent.” There were more than a few nods to the artist’s personal history and his antagonistic relationship with his home. The ancestral hall used in the show was split between the two galleries, but you could peer into the other half through a surveillance camera. It’s subtle, to be sure, but it’s also difficult to read as something other than a reference to Ai’s lived experience. The artist wasn’t throwing bombs, but he was still using his work to dissect culture. He commented on the choice to split the ancestral hall between two locations.

“I had to find two galleries and just show half of [the work] in each,” said the artist in an interview with Beijing Time Out. “That is the way to completely destroy the original feeling, because totality is the core idea of the Chinese culture. Chinese society and politics still cannot be at ease with that idea – which helps China, and stops China, in developing. My idea is to have a show, have a material, a physical metaphor to represent my current condition – and the time being of our time, our state of mind.’”

More of Ai’s ceramic-focused works were on exhibition. Spouts Installation, brought a thick carpet of 10,000 antique spouts, all from the Song to Qing Dynasties, to the floor of one gallery. Ai uses ancient ceramics to play with our assumptions about the past. In Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn he teases your instinct to protect an ancient vessel simply because it is ancient. Spouts may be destructive as well but it doesn’t feel like a provocation. Rather the spouts, which at first glance resemble a pile of bones littering the floor of the gallery, play with my concept of history. Their number, depth, and mass create an experience of the ancient world that is immediate and real, making me question whether my personal sense of the past is too thin, too flat.

There was also a reference to one of the stranger (I’ll stop short of using the word “grotesque”) stories to come out of the art marketplace this year. Ai Weiwei created replicas of the “chicken cup,” a porcelain teacup from the Chenghua era that depicts a rooster and a hen. The original was purchased at auction by private collector and businessman Liu Yiqian for $36 million. What’s more, Liu charged the purchase to his American Express card.

Liu represents a different kind of destruction: he’s passive where Weiwei is active. Ai offends sensibilities by “destroying” ancient, yet common works. But Ai works with intent while his counterpart appears profane. Liu Yiqian removed a piece of history from the public sphere by thoughtlessly throwing piles of money at it. A $36 million purchase and Liu couldn’t even be bothered to put on a tie for the occasion. The cup is gone now, locked away in a private gallery. It has the unhappy fate of being known more for its price tag than for its art. Ai would’ve given it a nobler death.

The chicken cup is notoriously one of the most counterfeited pieces of porcelain in China. In this light, Ai’s replicas also read like destruction, an assault on the original by creating knockoffs. A sick part of me wishes Ai went full-on Ken Price and created an army of these clones. Every time one sold it would chip a tiny piece off the original. The replicas would occupy a strange space in which they were both devaluing the original while also selling at high prices due to Ai’s name being attached to them.

If counterfeiting art and sawing a 400-year-old holy site in half qualify as subtle, I hope Ai Weiwei remains sneaky for years to come.

Bill Rodgers is the Managing Editor of cfile.daily.

Love contemporary ceramic art + design? Let us know in the comments.

Your writing is amateur bill