Art historian Miya Tokumitsu, writing for The New Republic, gazed deeply into how our society has been using the term “curation” to describe the selection process for everything from art shows to online retail to lowbrow clickbait content on the Internet.

In other words, almost nothing escapes curation, or at least the possibility of being curated. How did our world become a venue for curation? And how did curating, a highly specialized line of museum work involving the care, accessioning, and exhibition of artworks, come to mean, as cultural policy scholar Amanda Coles puts it, “just picking stuff?”

Tokumitsu’s discussion of the term soon launched into territory that made me wince: a concept described as “prestige appropriation.” I say this made me wince because she immediately quotes someone who is attempting to turn back the tide by sneering at the plebeians who presume to use a word that’s off-limits for people outside of the artistic community. Choire Sicha is cranky that “curation” is being used by bloggers to describe how they showcase online media.

“As a former actual curator, of like, actual art and whatnot, I think I’m fairly well positioned to say that you folks with your blog and your Tumblr and your whatever are not actually engaged in the process of curation,” wrote Choire Sicha at The Awl.

Sicha should take his complaints to Subway; I hear the people who work there have been shamelessly calling themselves “sandwich artists” for years.

His campaign, like all pedantic attempts to impose prescriptivism on a living language, is doomed. Words evolve; their connotations change as people find new uses for them. Tokumitsu explores this by comparing classic curation (a collaborative process) with curation as it’s used popularly, which signifies a more individualistic endeavor.

According to writer and art curator Rebecca Coates, fundamental to the present craze over curation as popularly imagined, is the emphasis it places on “personalization and creativity.” “Curation” has come to validate what would otherwise be simple preferences as not merely unique, but profoundly so.

I’m partial to Coates’s reading of the term, mostly because I’m a creature of the Internet and am more likely to follow the creative thoughts of interesting weirdos as opposed to personality-free institutions. The ease with which people can publish their work online makes these individual curators necessary. There is far too much media out there competing for my attention and I don’t have time to separate the wheat from the chaff on my own.

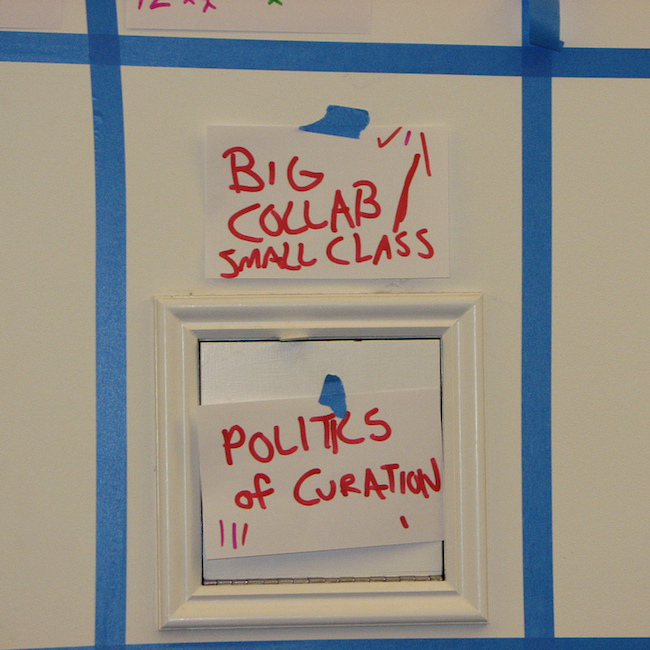

Illustration from The New Republic.

Which brings us to another, more troubling reading of how “curation” has changed in popular use. Tokumitso describes this as “consumption-as-authenticity.” The public at large is denied the feeling of autonomy and so seeks the feeling of control that “curation” implies.

The feeling of control that self-proclaimed curating can provide is in direct contrast to the loss of control unleashed by the very neoliberal policies introduced in the last decades. Flat wages, dwindling public services, and a relatively weak labor market have left many people disempowered and politically alienated… On the other hand, re-arranging “curated” compilations, be they stock portfolios or mood boards, can provide a much craved sense of power, excitement, and importantly—comfort— that comes from self-determination.

As abstract as this discussion is, we’d like to hear what our readers think. Do you get defensive at seeing “curation” adopted by other fields? Has it been given new life when applied to the oceans of media on the Internet? Are we searching for a security blanket to cover up our lack of autonomy? Tell us what you think in the comments.

Bill Rodgers is a Contributing Writer at CFile, a blog that curates news about contemporary ceramic art.

Add your valued opinion to this post.