The Last Sane Man: Michael Cardew – Modern Pots, Colonialism and the Counterculture

Tanya Harrod

Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2012

Hardcover, 380 pages. Illustrated.

“When Heaven has some great task in store for a man, it at first exercises his mind with suffering and his sinews and bones with toil. It exposes his body to hunger and subjects him to extreme poverty. It confounds his undertakings. By all these methods it stimulates his mind, hardens his nature and supplies his incompetencies. “

– Michael Cardew’s favorite quote from Confucius’s disciple Mencius

I was eagerly awaiting the arrival of Tanya Harrod’s The Last Sane Man: Michael Cardew – Modern Pots, Colonialism and the Counterculture, when a friend who had received an advance copy showed me the book. He pointed out a line inside the dust jacket that said this was the first biography of Michael Cardew.

He wondered if I was upset having written the first book about this potter, Michael Cardew: An Intimate Account of a Potter Who Has Captured the Spirit of Country Craft (Kodansha 1978). The clumsy title was not mine by the way, my editor at Kodansha took it upon himself to name the book and I was not thrilled. Even Word’s grammar check dislikes it.

Had the blurb said that Sane Man was the first book on Cardew I would have been livid. But the claim is correct. My book was a portrait, biographical in structure but not a biography. In retrospect, I would have entitled it Michael Cardew: A Primer. It did its job as Cardew himself reluctantly admitted a few years after publication. It introduced him to a much wider audience, particularly in the United States.

Harrod’s biography is the real thing, a magisterial achievement, a decade in the making, in an exceedingly difficult literary specialty. The depth of research, the meticulously detailed story of Cardew’s complicated life, fact-by-fact, insight-by-insight, covering 80 years of the 20th century is awe inspiring.

There has never been a biography like this in ceramics. Even the great Josiah Wedgwood, the subject of countless books, has not been accorded such a faithful, insightful and skillful exposition of his life. Maybe Harrod would consider righting this omission. Wedgwood deserves her.

Emmanuel Cooper’s Bernard Leach: Life and Work (Yale, 2003) was a failure as a biography but ended up having value as a compendium of the potter’s journals, which the author followed all too slavishly. However, it did point out the difficulty with biography. It requires a singular subject. Mere achievement (and Leach had oodles of that) does not do it.

Surprisingly, Leach did not have that magic “something.” Unquestionably one of the definitive figures in modern ceramics, he emerges in a long book as a bit dull and tedious, bemoaning constantly that he was a poor husband and father. (Harrod’s book provides a lot of competition from Cardew in that department).

A better biography can be written about Leach but I doubt ever a great one. I do not say this to belittle his considerable achievement. I am talking about the rare pepper in a personality and journey that sparks an excellent biography.

Cardew possessed that essence. Harrod never met him but anyone who did was struck by his electric presence, his charming arrogance and his enormous intellect, his huge toothy smile and, beaky nose and fierce inquisitive eyes, like an elderly eagle. In body language he was more of a stork, flapping arms and hopping from one leg to the other. Charles Counts called his overall presence “infectious humanity.”

Cardew’s life had a singular Quixotic mission; an Oxford graduate goes on a crusade, becomes a potter making country wares during the birth of the studio pottery movement and never wavers on his journey from one near impossible lance-tilting pottery project to the other.

His encounter with Africa, which was when he said “my life began,” is a terrific tale, worthy of the manly fiction in Boy’s Own Paper that was published when Cardew was a child; a fearless white male becomes an amateur geologist to find ceramic materials in deserted mines, survives attacks in a civil war, falls in love with an stunningly handsome 20 year old African, Koffey Attey (well maybe not this part, not then), saves Native pottery from a misguided program to upgrade rural poverty to the technical level of European peasant wares and is smitten by every malady that Africa could throw at this arriviste from Bilharzia to malnutrition and poverty.

Even this local color would not be enough without Cardew’s extraordinary mind, his determined selfishness, which gives such momentum and his constant, fascinating erudite self-analysis. Harrod teases this all out in her book, Cardew’s gregariousness, ruthlessness on matters of principle (even though he was often wrong), his tough judgments, indomitable spirit in the face of constant health problems and seemingly impossible odds and sudden bursts of generosity. If the list sounds contradictory, it is, as are most significant lives.

Harrod’s relationship with Cardew is both as chronicler and chide. When it is called for she briefly admonishes him for his failings, like a doting but exasperated and knowing daughter, often pointing out his unkindness, and the unreasonable treatment of people around him who deserved better, not the least his family. Even so now and again she has just had enough of Cardew’s tendency towards sanctimoniousness. I found this charming.

When I put the book down the first time I shook my head in disbelief at what she had wrought, the immensity of detail, all the foregrounding and backgrounding that fleshed out people, events and places through this diverse panoply of life.

However, I was asked to be tough. The first read left me astounded and yet something was missing. I could not quite put a finger on it. Harrod had successfully created the man in 3-D, his unleashed enthusiasms, his spontaneity, his liberal politics, his crabbiness and persistent irritable inner critic, his almost inhuman work ethic, his bursts of radiant joyfulness. It all seemed to be there. So what was missing?

Halfway through the second read it struck me. Cardew’s distinctive voice was absent: the sound of him talking. It can be heard, loud and clear through his writing; the pauses, the hammering home of a crucial phrase, the flourishes, the sharp stab of the pen, the impatience with and contempt for poor arguments and the occasional tone of smugness after delivering a brilliant bon mot. All together Cardew in full voice was mesmerizing, like a performance of Shakespeare by a brilliant actor.

Harrod keeps the quotes from Cardew very disciplined, clipped, short and pithy. There are few occasions when a letter or article is quoted at any length. She talks of his dissatisfaction with contemporary ceramics. He discusses that issue in several essays and his arguments are persuasive and intriguing. But we do not hear him make that argument.

His literary voice, and he was an excellent writer, so close to his spoken one, is largely absent. The omission is consistent and was clearly a choice on Harrod’s part. I can understand that she did not want this book to have the feel of a doctoral thesis with needless and lengthy quotes but more of this would have enhanced the book.

Secondly, I found that the first half of the book was more convincing; indeed it is masterful, subtly conveying the curious world of English bohemianism and rustic perversity of the arts and crafts movement.

Harrod provides more detail than connection once Cardew gets to Africa. His relationship with his African staff and students is never quite conveyed, nor their sense of him. There is not a paragraph where his attachment to the land in particular is convincingly communicated. And that was an intense part of his love of Africa.

Neither is his intimacy with its people and culture explored.

There is a moment in the film Mud and Water Man when Michael pays his first return visit to Abuja in many years. In Africa there is a non-verbal language that is spoken throughout the continent. As people approach each other, even from afar, their bodies begin to move, sway, sometimes even dance and by the time they are in earshot a lot has been said.

I do not see that in Europe, the US or Asia. It is distinctly African or at least that is where it is most elaborate. And as the people from Abuja come down the hill to greet him you see Cardew’s body began to move and answer their welcoming choreography. This is not your average white man in Africa. He feels them. He was no longer the patronizing observer who arrived in 1940.

Lastly, there are a few small quibbles. Why are photographs in trade books always handled so poorly? It is almost a snobbish academic affection. The color section of Cardew’s pots is awkward, with poor cropping and an uneven quality of photography. It could have been much better.

There are countless moments in the book that are transportive and perfect. But the closing chapter on Michael’s death stands out. Death is often handled in a perfunctory way, but Michael’s last weeks are conveyed by Harrod with such tenderness and clarity that one felt present at his bedside. (I regret not being there.)

It was loss but not tragedy. On his last trip to Los Angeles Michael, two years before his death, had confided to my partner Mark Del Vecchio and I that he was exhausted, he was ready, even eager to go.

Harrod closes the book with a pointed summary, not of him as a potter (indeed we do not really know the full opinion of his work) but on purely personal terms:

“Mariel and Kofi were the two people Michael had loved best. Kofi found life difficult without Michael’s support, technically, emotionally and financially. Mariel, until she fell ill, had created her own complete world but who can say who missed Michael most? He turned both their lives topsy-turvy and in different ways pushed both of them to their limits. Michael was, therefore, in part a destructive force – an imperfect husband, an absent father, a closet homosexual and a reluctant colonial whose influence over Kofi’s life owed much to that colonial situation. Yes his biography can equally be seen as brave and unusual. From the politically confused and polarised inter-war years right up to the turn to neo-liberal ideologies in the 1980s, his story illuminates overlooked ways of living.”

I admit that my criticisms may be too personal, too crafted for my own expectations, which are not those of the general reader. I both knew Cardew and am a white African with family roots that go back in that continent to 1700. So my needs from the author may well be unrealistic.

None of my critique above changes my respect for this magnificent book. I always know when a book on ceramics is impressive; there is a nagging feeling of jealousy that I had not written it. (I am less territorial on other subjects.) This book made me very jealous indeed. Michael has been well served.

Garth Clark is the Chief Editor of CFile

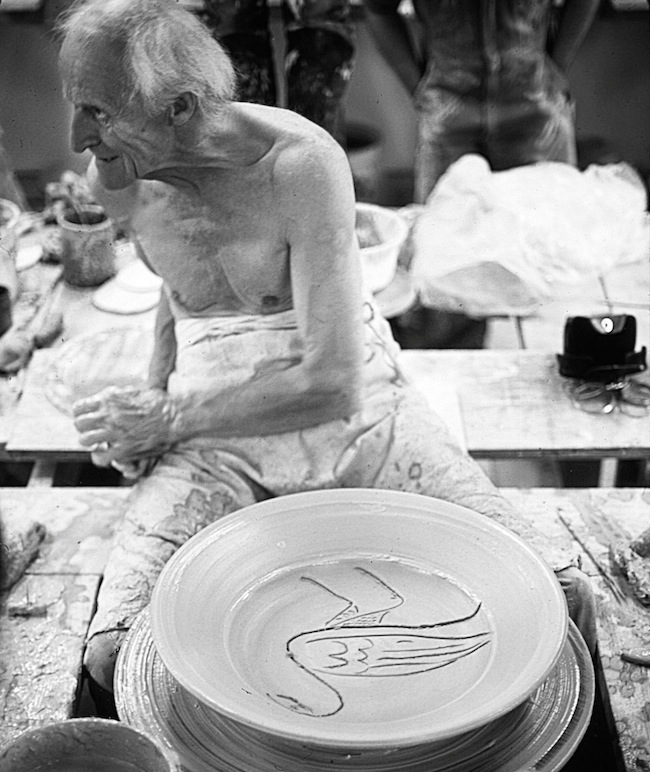

Above image: Michael Cardew decorating a plate.

Any thoughts about this post? Share yours in the comment box below.

Images from Tanya Harrod’s book on Michael Cardew, The Last Sane Man.

Read Garth Clark’s editorial on tradition in ceramics

Read Garth Clark’s Interview with Matt Jones

Read our post about Marty Gross’ Mingei Documentary

Read our post about Mark Hewitt in Abuja

Add your valued opinion to this post.