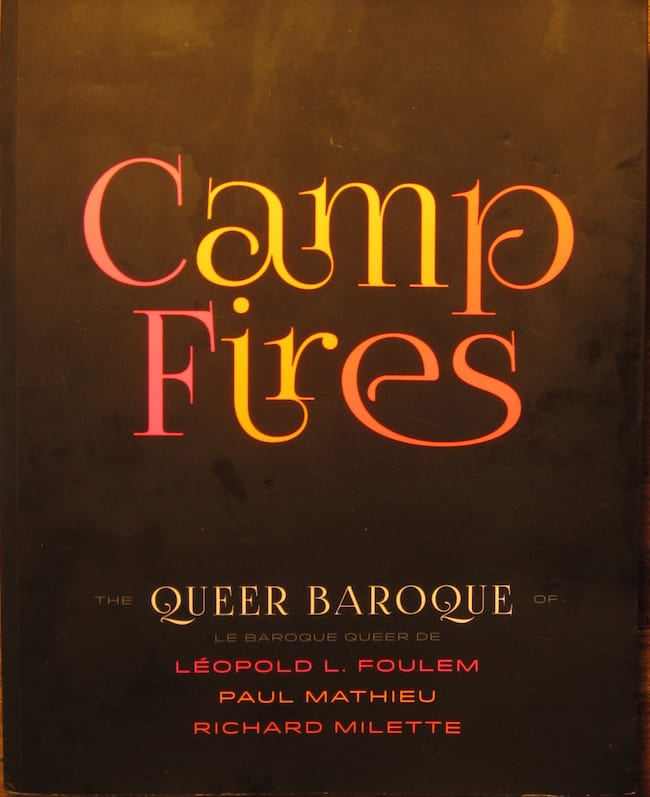

Camp Fires: The Queer Baroque Of Leopold L. Foulham, Paul Mathieu, Richard Milette

Edited by Paula Sarson with forward by Kelvin Browne, and an Introduction and essay by curator Robin Metcalfe. French translation by Colette Tougas

Gardiner Museum, Toronto Canada, 2014

Softcover Exhibition Catalog, 144 pages. 87 illustrations. 9.4 x 11.8 inches

Above image: Camp Fires exhibition catalog cover. Published by The Gardiner Museum, Toronto, Canada.

Camp Fires: The Queer Baroque of Leopold L. Foulham, Paul Mathieu, Richard Milette is a pretty, well-assembled, thoughtful, ostentatious and dramatically flawed work. The error is not to be found in its beautiful design, perfect and relevant photographs, and most certainly not in the works of art represented therein, but rather in the idea proffered in its preface “Campfire Notebooks.”

Before we step onto the platform, however, it will be worthwhile to note the origin of the catalog. “Camp Fires” was published to coincide with the Gardiner Museum’s opening of an exhibition with (of course) the same name, which, in turn, coincided with Toronto’s WorldPride week. You can read Garth Clark’s review of the exhibition on CFile.

The relevance of these three artists could hardly be contested not only as ceramicists, but as teachers with a strong sway on what ceramic art is and what it will be.

So, where is the fault in all this? It’s in an idea put forth, not by Foulham, Mathieu, or Milette, but by the curator Robin Metcalfe. Gathering to his aid some random ephemera from his own past (his thoughts and opinions about “Camp Fire Girls” and something called a “campfire notebook,” which he tells us is, “a type of notepad I remember from grade school…”) Using these obscure tools he makes a leap to Susan Sontag’s highly celebrated writing “Notes on Camp,” the very first manifesto-esque piece of writing that tried to define Camp and what it meant as a theme.

I say theme, because Camp is not an art as Baroque is an art. Camp is, more often than not, a byproduct; it is the beauty, the singular vision, the overwrought world created so forcefully and in a dialogue so uniquely its own that it emerges as ornament, as a built (as opposed to felt) thing. In Camp gestures are teased to an extreme.

A savor common to Camp is the sense it creates of a foreignness, an almost glaring otherness as is often created when cultures are mimicked by those with no cultural understanding of what they portray. An early section of Sontag’s essay contains a famous list, however incomplete, of things she felt exhibited the elements typical of Camp. Among them: “The Enquirer, headlines and stories,” “Aubrey Beardsley drawings,” “the old Flash Gordon comics,” and “the novels of Ronald Firbank and Ivy Compton-Burnett.” This list is very diverse and yet all of these things contain something in common, over-posturing.

In the novels of Firbank, for example, the characters, settings, and even speeches are so mannered, so focused on high society and aesthetics that peacocks embroider the grounds and occasionally cry out, gossip is not only a mark of class and being well informed, but seemingly the only pastime. Firbank’s novels have very little room for the familiar world as all importance is placed on attending readings of Sapphic fragments and flattering one’s own ego with the most obscure of tasks such as, “to erect… a window in some cathedral… that should be a miracle of violet glass, after a design of Lanzini Niccolo.”

The Diorama-like sets, explosive emotions, oddly rapid pace, and earnest seriousness of many operas can also serve as a classic example of Camp.

The works of these ceramists may share some elements of Camp as well. They utilize humor, use phalluses, vulgarity, and queer culture color swatches (neon, pink, gold, etc.), and set a LGBT theme, but they always represent, as a whole, a diligent and exquisite dialogue with the history of ceramics. However, Milette’s insistence that Camp be forever a queer medium is off. Camp may have been a jewel in the crown of queer culture, but it has expanded. Think of low-riders with their white leather interiors, metallic purple, red, blue and green paint jobs and golden rims. There is something very Camp about this trend in culture which, rather then being exhibited by the LGBT community, is a hallmark of an over-masculine and heteronormative culture, particularly among motorheads and sports-driven men. Another example could be the den of a sports fan wherein everything is team colors, every item, piece of furniture and all that is hung upon the walls, this is another Camp scene, but one removed from its queer roots.

Take, as an example, the works of Richard Milette. Milette is constantly, almost painfully making reference to the history of ceramics as an art of form. In the three pieces Jealousy, Seduction, and Sacrifice the words that serve as their titles are promptly displayed upon a field of marble. They at once remind one of ancient Greek pottery with their form, and this is heightened by the appearance of slab marble, which we readily associate with the classical world. The words themselves stand in for stock scenes, think the death of Hercules for example, which would be a good scene for sacrifice, or Leda being seduced by Zeus in the form of a swan, which would be a good scene for seduction. By substituting the words themselves for any such scenes, Milette places the prominence not on the exterior art of the piece, which he would seem to maintain is an afterthought, but rather more heavily on the form of the vessel. He seems to say with these choice words, pick a scene, any that comes to mind will do. This highly advanced concept is well beyond the theme of Camp.

Metcalfe, in his essay, doesn’t want to share. He doesn’t want to admit that Camp has evolved to make room for those of a diverse cultural background leaving the queer community without exclusive rights on one of their formally brightest flagships. Camp has been subsumed by mass culture, so that today it is a motif shared by all. Metcalfe sees Sontag’s unwillingness to place Camp in a squarely queer tradition as “coy.” What he misses is that “Notes on Camp” wants to open up the medium and make it more accessible for all cultures.

But Metcalfe doesn’t share this opinion, rather he sees Camp as something genuinely gay and, not only that, as gay themes trying to emerge through ostensibly heterosexual themes:

“…the beautiful lies of the operatic stage become grist for the mill of Camp, narratives whose artificiality can be celebrated, not with mere indifference to their apparent content but with implicit appreciation of the hidden narratives, of the repressed Queer content that lurks within.”

Here we are privy to the fault in Metcalfe’s thinking: any medium that contains exaggeration, that pushes itself, knowingly or not, over the top becomes such “grist.” Metcalfe, by his definition, allows himself the privilege of calling anything he finds to have a “repressed Queer content” Camp and therefore, via his own default, queer under the surface. But this is a flawed and strangely exclusory view.

Photo spreads from the Camp Fires exhibition catalog.

Yes, the works of these three artists is highly mannered, given to both pop and even kitsch reference, they enjoy a playfulness and exuberance, but they are not prone to that foreignness so key to Camp.

What Metcalfe wants to say is clear, but tenuously defended and, in the end, falls to ruin. It is, for lack of a better term, a little Camp. However, the catalog is saved in that it is a great retrospective look (via pictures) into the valuable works of three great and closely-associated artists.

Christopher Johnson is a contributing writer at CFile.

Any thoughts about this post? Share yours in the comment box below.

Thank you for mentioning our catalogue once more. However, there were three ceramic artists participating in this exhibition. Unfortunately, not only was my family name misspelled (Fulham instead of Foulem), but I did not see any of my works discussed in the text. Isn’t that incongruous?

Of course, I am not blaming you, but I find it awkward that the writer did not at least mention why he overlooked my work entirely.

Warmest regards,