BROOKLYN — We recently wrote about Prune Nourry’s army of female terracotta warriors. Her newest large-scale installation work, Anima, recently showed at The Invisible Dog Art Center (Brooklyn, until April 14). In it, Nourry revisits the theme of cultural dialogues. Her terracotta soldiers were a comment on gender preference, but in Anima Nourry explores how people in a dwindling Mayan tribe view their relationship to the natural world.

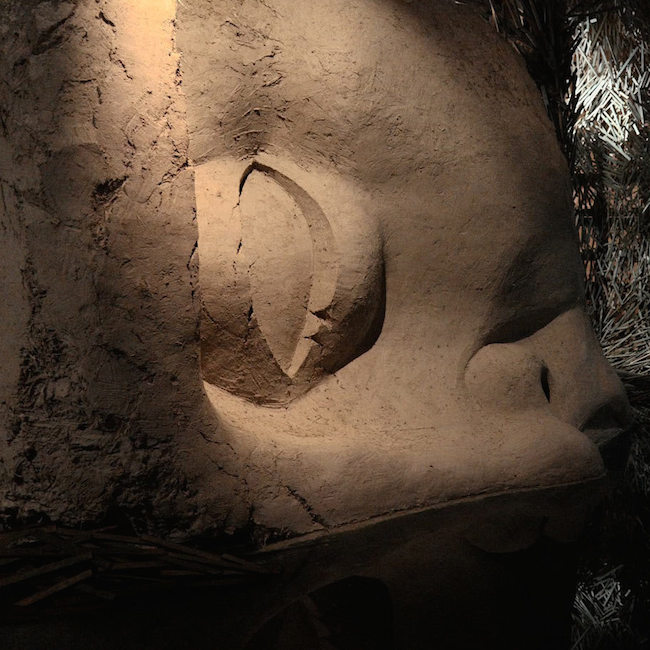

Above image: Prune Nourry, Anima, 2016. Photograph by JR.

There’s a treat for fans of myth and folklore. Nourry worked on the exhibition with anthropologist Valentine Losseau, who studied the Lacandon people in Mexico. They told Losseau a story of K’in Obregon, who is part-patriarch, part-magician. The great part about his legend is that it took place within recent memory. K’in wasn’t confined to some far-off, idealized past where he fraternized with other culture heroes and gods, his story begins in the 1930s.

Obregon was taken to Paris in 1937 where he was installed in the Universal Exhibition. I say “installed” because Nourry describes an experience in which Obregon was treated as an object. It was a fad at the time for to put tribal people like Obregon into human zoos where they could be gawked at by the public. It reads like an evil version of National Geographic.

Obregon returned home from Paris and then died some years later. One day, though, he came home claiming he had been reincarnated. People tell his story to this day and that’s the exciting thing, not whether his story is true, but that a myth about a dying and rising man was created only a few generations ago. I know very little about the culture at hand, but it wouldn’t surprise me if there were parallel stories that preceded K’in. If I had to take a guess, I’d say that he was slotted into a resurrection story that existed already, probably about someone who had visited a far-away place and returned home with spiritual and material gifts. It’s not much of a stretch (for me, anyway) to substitute Paris for the netherworld. Obregon must have been a fascinating person to have this story grafted to his biography.

Myths are like codes that transfer information about a culture’s values and attitudes regarding the world at large. Though I am interested in the historical K’in Obregon, that’s secondary to the question of why people tell his story. What can you learn about the people from their myths? Nourry doesn’t present a tidy answer to this question, but she does invoke another myth that can be considered in context with the first. The emphasis is mine.

The second story Losseau shared with Nourry explains “Anima’s” visual language. “She recorded a young man telling her that in his last dream he transformed into a fish. He was in a pond and he stepped out to get some air and he saw his father, who was transformed into a wild pig, walking forward to get a drink of water. Valentine then walked three hours and went to the house of the man’s father. She asked him to tell her about his dream and he told the exact same story: he was a wild pig and he saw his son as a fish as he was stepping to a pond to drink some water. For the Mayans, there is no magic behind this. It is normality,” Nourry recounts. With this as impetus, Nourry invited magician Etienne Saglio and scenographer Benjamin Gabrié to join in the collaborative construction.

I’ll take a stab at reading these two, with apologies to the Lacandon people. A theme I’m noticing is that existence is malleable, fluid. There isn’t a boundary between man and animal, earth and heaven, life and death. Passing over into different realms is so easy you can do it in your sleep. This is interesting because it’s so different from my own concept of the universe. I live in dualism. I exist in the world like Fortress Bill Rodgers. My body and mind are hermetically sealed and all that enters into my space must first pass through many filters before I can engage with it. Because of that, I suspect that I can never really know that which is not myself. It’s a lonely thought, but that’s fine.

Anima is the alternative and Nourry makes the case for it in installation art, a form that gives her maximum control over the viewer’s perspective. Our worldviews are like houses we inhabit. We’re agoraphobic in that regard, so to shift our perspective so radically we may need to change everything we see, feel, smell, taste and hear. I doubt that someone could ever fully step into that worldview if they weren’t raised within it. It’s like one of those curves on a graph that always approaches zero but never reaches it. That’s okay! In realizing that I have to give Nourry credit for not sermonizing the alternative. She’s not arguing that it is The One True Way. She, like her anthropologist friend, is presenting it for study and in so doing the world is a little bigger than it was before.

Prune Nourry is a French artist who lives and works in New York. Trained as a sculptor, Nourry has developed a multi-disciplinary approach, favoring media that the audience can interact with and participatory art experiences. Nourry graduated from the Ecole Boulle, Paris in 2006. In the United States, Nourry is best know for Spermbar, an installation and performance on 5th Avenue, commissioned by The French Institute Alliance Française (FIAF) for Crossing the Line Festival, New York, 2011. Exhibitions and performances stemming from her 2010 project, Holy Daughters, have taken place at Centre Pompidou, Paris; Polka Gallery, Paris; Galerie Henrik Springmann, Berlin; The Invisible Dog Art Center, New York; Flux Laboratory Genève, Carouge, Switzerland; and New Delhi, India.

Bill Rodgers is the Managing Editor of cfile.daily.

Do you love or loathe this work of contemporary ceramic art? Let us know in the comments.

This is all very much inspiring, great art.

Thank you.