YPSILANTI, Michigan — We have a special treat for you on this Friday— images from not one, but two outstanding exhibitions by Trevor King. King, according to his biography, is a visual artist who works with sculpture, ceramics, video, sound and photography. He was born in Western Pennsylvania (always nice to see a fellow inmate of the Rust Belt doing well for himself) and he grew up witnessing how the area changed following the crash of industrialization. With that as his background, his work studies questions of identity, labor, art and entropy. His own biography, oral histories from others, and a desire to document everything are the sources for King’s work. In 2014, King was awarded an International Institute Fellowship to work under the immortal British sculptor Antony Gormley.

The first series we have for you today comes from listener (Detroit, March 2015) at the 9338 Campau Gallery. A field of unglazed porcelain vessels sat on the floor of the gallery. The pots were accompanied by a sound sculpture that seemed to work on the same principal as sheet reverb devices from old recording studios. The steel sheet resonates with an audio loop of tones that were recorded within the volumes of the pots on exhibition. I’ve embedded a recording of that sculpture in this post. If you’re a fan of ambient, droning soundscapes you must hear it.

It’s easy to see that this is a nod to King’s industrial background, but the sculpture is elevated away from the other connotations about the Rust Belt. The sculpture reaches a state of purity by removing humanity from the equation. Once we’re not around to dirty up the scene with our grit, economic concerns, and Bruce Springsteen-style melancholy, the steel can ascend into a place that is purely industrial. It doesn’t seem to care about people at all, which is what I love about it.

This isn’t to say that humanity isn’t present in the exhibition as a whole. Really, what we’re seeing in the pots and the sheet are two bookends to labor, separated by several thousand years and a few feet of gallery space. Pots are believed to be a more grounded, earthy profession than factory work and yet the sheet of steel vibrates with the same kind of energy that went into the pots. This isn’t simply an observation, or a platitude. In it I see a demand that we respect all forms of labor. No small amount of bitterness exists back home, where unemployed steel workers feel as though the entire country has written them off. It’s created a poisonous cynicism that has held the area back from accomplishing anything new since the mills chained their gates shut all those years ago. A little concern for the dignity of blue collar workers would have gone a long way.

From the gallery:

“If art making is to be considered an act of communication,” King states, “then I am more interested in listening than speaking. What he is listening for is most likely unnamable, but some of the frequencies he monitors include the cultural landscape of the blue-collar post-industrial region of west Pennsylvania where he grew up, and the millenniums-long collective memory of crafts like vessel throwing. By doing so he searches for the universal in the everyday, perhaps encouraging us to similarly listen.”

Above images: Trevor King, Listener, 2015, installation view, unglazed porcelain vessels and steel sound sculpture. Photographs by Math Monahan.

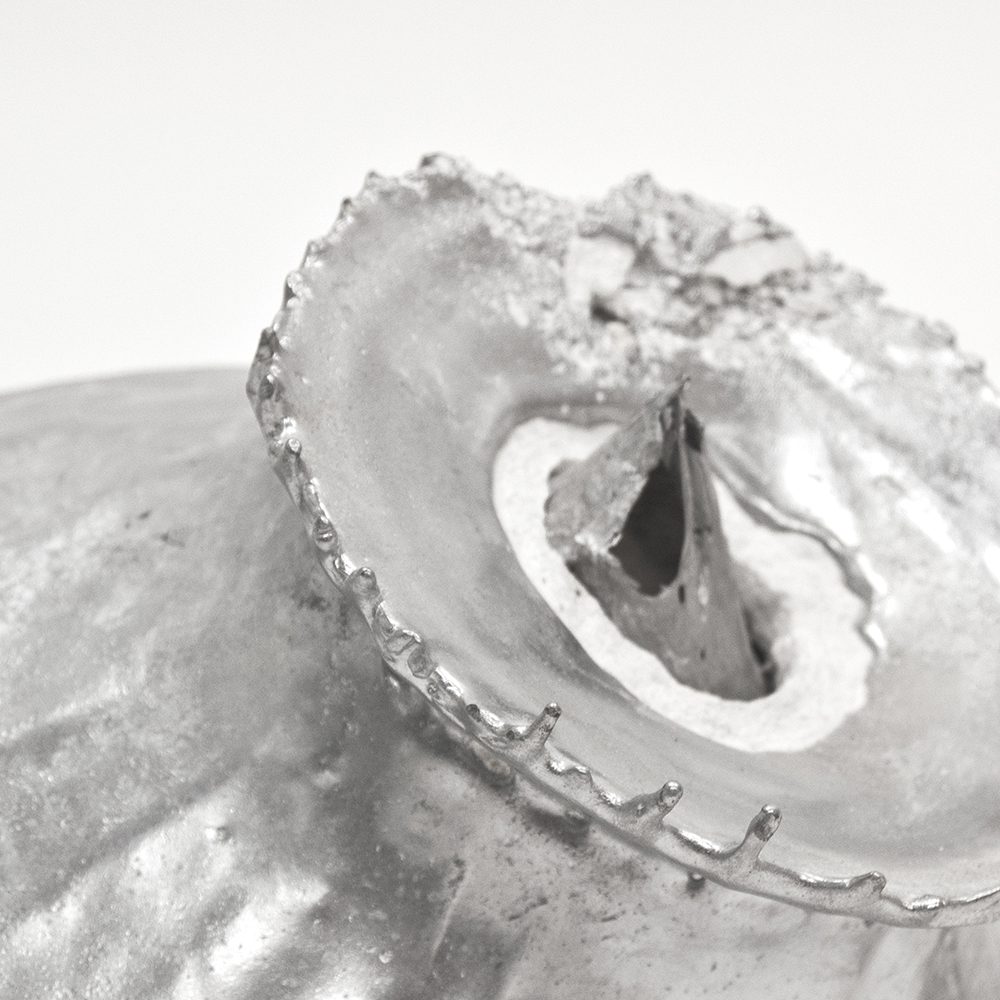

King’s next group exhibition was held at the David Klein Gallery in Detroit, First Summer: Part 1: Ebitenyefa Baralaye, Liz Cohen, Matthew Hawtin, Trevor King, Anthony Olson, Mark Sengbusch. For this one King showcased his Aluminums series. I’ll step aside and let Trevor describe it in his own words.

At the western edge Pennsylvania there is a small state park called Moraine. This craggy landscape, scattered with bus-sized boulders, is aptly named, a moraine is the accumulation of rock debris carried or deposited by a glacier. Being in this space, you are made aware of the deep geological history of our earth, the slow churning of the ground beneath us forming.

I think that making pottery is like this— walking through one of man’s oldest and most fundamental creative and self-realizing traditions. Walking on the surface of the earth, in the dirt and the mud, just to see your footprints left behind you, or to discover a dark cave carved out by a calm stream over centuries, or to see your fingerprint in the throw marks on a soft bowl.

I was taught that the mystery, or the spirit, of a pot is held inside of it. This is an old notion in old media, and it is as timeless and important as ever. I think that the promise of making a pot is simply in that we can do it. Using what is in us, we can literally shape the space around us. The inside of a pot is a reminder of where that possibility rests. In my Aluminums series, I am burrowing into this interior space, spelunking.

The works are made by blending wheel thrown processes with lost wax casting methods. I begin by throwing voluminous porcelain forms on the potter’s wheel, typically using the stacked bowl construction utilized for making “moon jars.” Once the forms are leather hard, I fill their interiors with a thick layer of casting wax, then remove the clay so that what remains is a registration of the interior of the original vessel. The waxes are then invested into ceramic shell and melted out to make space for aluminum. In the casting process, I intentionally cause core shifts to utilize the liquid quality of the molten aluminum and the geological craggy nature of the ceramic shell. The final artworks are visible remnants of these materials: forming, pouring, melting and dissolving.

Initial commentary by Bill Rodgers, Managing Editor of cfile.daily, followed by text (edited) courtesy of Trevor King. Photographs courtesy of the artist.

Do you love or loathe these works of contemporary ceramic art? Let us know in the comments.

Add your valued opinion to this post.