Peter James Smith is a quintessential New Zealand painter of black grounds, dark landscapes, and evening skies shot with fading sunlight. His practice is built upon the traditional painting medium of oil on linen, now he is extending this same painting process to installations and painted objects. He is widely published as a professional mathematician and holds the degrees: BSc (Hons), MSc, PhD with a Master of Fine Art in Painting. He is Professor of Mathematics and Art at RMIT University, Melbourne and he has had more than 50 solo shows, participated in many group exhibitions, and curated exhibitions throughout New Zealand and Australia. His work is represented in many public, private and corporate collections in New Zealand, Australia and internationally.

As a painter and mathematician with a lifelong affiliation to blackboards and the revelatory mathematical explanation…I paint equations from the inside, on the cusp of their development. This includes the crossings out, and the blackboard erasures for the brick walls and blind alleys of failed proofs. (Peter James Smith, Truth + Beauty, exhibition catalogue, 2006).

For the past few years, he as been doing something that was known in the 18th century as “clobbering,” taking an existing ceramic and altering it, a common commercial activity at the time. Today the same license, albeit with a postmodern agenda, is termed appropriation. The purpose of clobbering was rarely ironic, it was not meant to critique the original; the purpose of adding surface painting and other embellishments was to make the object more desirable and therefore more sale-able at a higher price. It was a popular home industry.

But the word, drawn from street slang, has tough roots. Webster’s Dictionary gives the meaning as: 1. to beat or batter 2. to defeat utterly 3. to criticize severely. Another meaning is to use it as a noun in which case it refers to possessions, one’s clothing or belongings. This etymology suggests that to clobber another’s ceramic creation was in some sense, even centuries ago, seen as an act of violence.

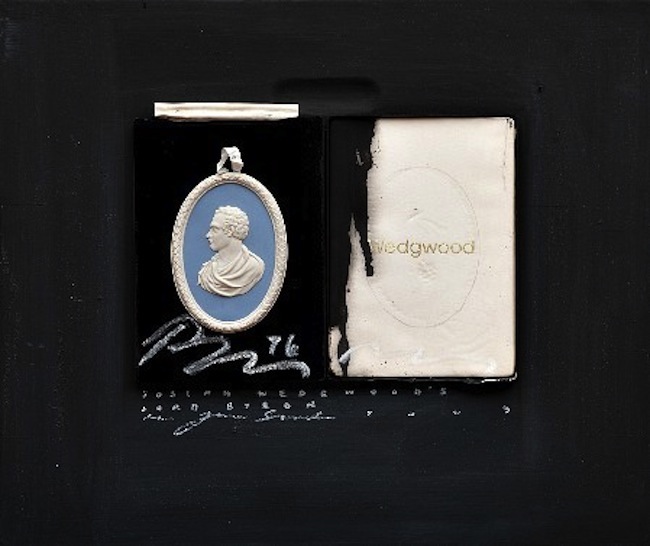

And that would appear true of Smith’s art, as black ooze, not unlike an oil spill, invades and threatens to overwhelm actual examples of Wedgwood’s delicate Jasper wares. Yet, remarkably, there is almost a feeling of tenderness to this intrusion. What remains on view of the original seems even more beautiful and ephemeral in contrast to the black. The elegant penmanship that accompanies the black has such refinement that the end result, while unquestionably current and contemporary in its presence, retains a gentle romantic quality sans cloying sentimentality. Thus, following the latter meaning of clobber, the work has been given 21st century currency—and literally re-clothed.

For those who want go a little more deeply into the work and its past history, Peter James Smith’s art has a hundred ports of entry. One can see Jasper ware simply as the commercial success that it was and still is. Or one can view it as the great Wedgwood’s only personal aesthetic achievement (for the rest of his genius lay in mass marketing and pioneering industrial manufacture). One can further link it to Wedgwood’s appropriation of the Roman glass Portland Vase, one the most famous antiquities on earth, which he remade in Jasper ware. Wedgwood then presented it as the first limited edition ceramic in the world and sent it on a tour of the royal capitals of Europe. (Smith dealt brilliantly with the vase in an earlier work Truth and Beauty, 2007, which is pictured below).

The presence of the Jasper wares inserts discussions about neo-classicism, early consumerism, art history, taste, connoisseurship, and even the marketing of art. It is also interesting that Smith has created art where almost any viewer can appreciate the powerful graphic presence of his sculpture and maybe even pick up a few of its cultural implications. But for those who bring some knowledge of Wedgwood’s role in the 18th century and the birth of the modern, the banquet of meaning and enjoyment that these clobbered objects offer is rich and limitless. The deeper we dig, the greater the feast. Smith makes antiquarians of us all.

Garth Clark is Chief Editor of CFile.

Above image: Peter James Smith, Josiah Wedgwood’s Lord Byron, 2009. Oil, enamel, metal, cloth and Jasperware on computer case. 390 x 460 mm. Courtesy of Flinders Lane Gallery.

Peter James Smith, Blue, the Vault of Heaven, 2011. Oil and enamel on Wedgwood Jasperware mounted on black shelf. Dimensions variable.

Peter James Smith, Blue, the Vault of Heaven (Detail), 2011.

Peter James Smith, Let the bright seraphim, 2009. Oil and collage on linen. 760 x 610 mm.

Peter James Smith, Truth and Beauty, 2007. Oil paint and 19th century book.

Peter James Smith, Paradise Lost II, 2007. Oil and enamel on Jasperware Wedgwood with stand, 140 x 120 mm.

Peter James Smith, Paradise Lost IV, 2008. Oil and enamel on Jasperware Wedgwood with stand, 140 mm. All images courtesy of Flinders Lane Gallery.

Add your valued opinion to this post.