LARVIK, NORWAY — A little girl sits on the floor making shadow animals against a lamp. Innocent enough. Close by, though, a shirtless boy about the same age aims a Kalashnikov rifle at a target much taller than he is. A few paces further, another girl studies the vortex spinning through her stomach the way you or I would study a suspicious mole on our skin.

Though she argues she’s not a dark and dreary person, Norwegian sculptor May von Krogh is willing to embrace uncomfortable realities about childhood. Her ceramic subjects occupy a moment just before the presumed innocence of youth is ripped off like a bandage. The effect isn’t to abuse or horrify, it’s more solemn than that. It feels paced. In those children I see anxieties that I carry myself and I nurture those anxieties as quietly as they do, my silence belying my growing alarm.

May von Krogh, Angels trumpet and the milky moon violin; installation of ceramic sculptures, painted walls and sand. Click to see a larger image.

That anxiety can be internal, as is the case with Angels trumpet and the milky moon violin, the sculpture I mentioned earlier with the vortex. The girl has a morbid interest in the hole inside herself and you can just barely tell that her brow is furrowed. It’s an intersection where interest meets concern. You could throw a few readings on the image of a void opening in someone’s body: depression, unfulfilled expectations, eating disorders, etc. The dead lamb near the girl complicates things. It looks as though it died because of some internal pressure.

It’s appropriate that I’m writing this on Good Friday because von Krogh sees a religious meaning in her work. She told Empty Kingdom in an interview:

At first, I only actually thought of the sentence: ‘Mary had a little lamb’, and of this image of a girl and a lamb. I also thought about the name Mary, and how it was kind of loaded with religious/spiritual meaning, as Virgin Mary is a classic symbol of innocence and purity. The clear conscience and the universal love between Mary and the lamb in the nursery rhyme makes it kind of trivial and light, and by turning the characters into this grotesque setting, they become more like martyr symbols, where their universal love will keep on existing beyond borders of time. The combination of something beautiful and fragile and the grotesque has always fascinated me, and I believe it awakens feelings and thoughts that wouldn’t appear without this duality. Usually we don’t want to see what is pure and innocent in combination with the grotesque.

We catch Mary and the lamb at the instant of transition, where they leave innocence and confront grisly reality. I can’t help but think about the feeling I had when I first doubted Christianity. I was six years old, playing with toys in my bedroom when (as though it came from an external source, which is ironic) the thought “God’s not real,” entered my head. The sensation felt like taking a step down a flight of stairs only to realize that the next step wasn’t where you thought it was. There was a burst of adrenaline as I immediately began to worry if even having the thought I just had was going to send me to Hell. Even today I can remember the certainty I used to have, the assurance that things were taken care of. That feeling is impossible to square with my current understanding of the universe. I can’t pretend I don’t have these doubts any more than I can decide to stop seeing the color blue. The lamb’s dead. Certainty left in the most visceral way it could.

This isn’t a dig on the piece, but it does look like Mary is navel-gazing. Though many of von Krogh’s pieces are concerned with our inner drama she does hit on anxieties from sources external to us. Galleri Ramfjord states in their bio about von Krogh that her work questions how we interact with the outside world. For You a Thousand Times Over depicts a shirtless, shoeless, boy aiming a replica of an AK47. I’ve seen some images with the AK47 removed, and I’d be very interested to listen in on the discussions leading to its removal. I’m sure they were heated. Absent any political argument about guns, the gun makes the work. She explains:

In my previous work, like the more naturalistic pieces of mine from my MA, I had been deeply into the theme of children in armed conflicts. The reason for me getting into this in the first place was because I experienced becoming a mother myself and started questioning the distortions in the world and how we interact with the world around us. I had never been a particular politically active person, and it was not my intention to do politically motivated art, either. I just got emotionally touched, and tried to put some of that feeling into my work.

Usually with political work you expect some sort of appeal from the subject, something that demands action on your part. You don’t get that with the boy. He’s not crying or in visible pain. He’s expressionless, suggesting that whatever horrible things he’s experienced have done their work and left long before we met him. The mass of emotional scar tissue seems to change the question from “What will you do?” to “What could you possibly do?” That doesn’t give you a pass, though! You can’t escape into nihilism. Remember the title: For You a Thousand Times Over. Not one boy, thousands of boys. Not one psychologically destructive story, thousands of them. They’re visited on you again and again, though you’re on the other side of the planet and (understandably) at a loss for how to help them. It’s paralyzing and part of me hates that about this sculpture. But it’s also the truth. I don’t have an out when I see stories about these children on the news, why should I have one here? von Krogh isn’t insulting my intelligence by lying to me, telling me that I could save this kid by sharing a Kony 2012 meme on my Facebook page. She’s articulating my experience for me, the feeling of turning away simply because I have no agency in this situation. It’s cold, but at least this way I can acknowledge my feeling of powerlessness rather than doing what I’ve been doing up until this point, which is burying it.

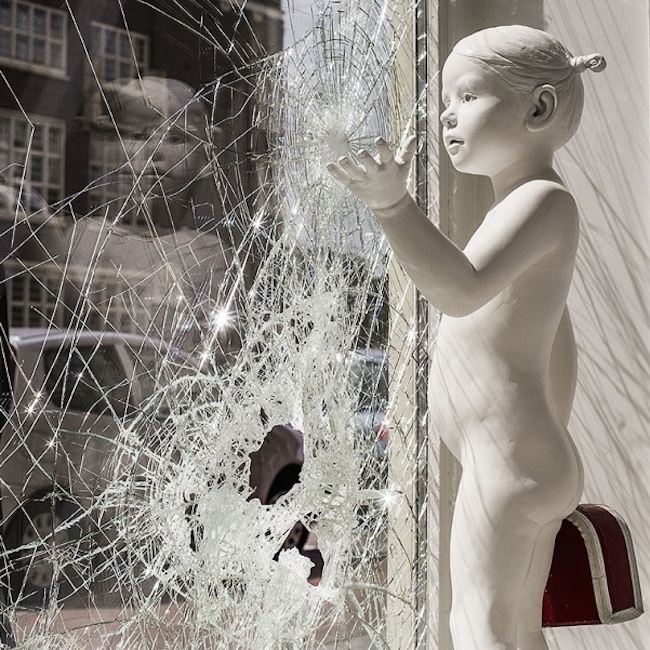

Children in peril is a well-used device in narrative, except that it’s usually delivered with a sense of urgency. In your rush to protect a child, you have no time to think. But the sculptures aren’t about to wander into traffic or touch a hot stove, they’re threatened by more insidious dangers. von Krogh slows the peril down to a crawl and in doing so she gives us time to reflect on our response. Assuming the boy with the AK47 is real, what good could it possibly do for some well-intentioned person to pry the gun out of his hands? Did that save him? That kneejerk response says more about the person acting on it than it does the sculpture. Take another look at the feature image in this post. Did you notice the broken glass? We’re told that a vandal, upset by the naked girl standing in the gallery window, tried to destroy the window and the sculpture. I believe that this person was acting from a desire to protect children. However, they projected their anxiety about child predators onto a sculpture that conveys no sexual thought. By trying to protect that child, the vandal became a threat to her safety and robbed her of her innocence. Through no fault of her own she became a vessel for our fear and anxiety. Now, juxtaposed against the spiderwebbed glass, the girl looks as bewildered as her friend with the vortex in her chest.

von Krogh (b. 1977) lives and works in Larvik, Norway. She obtained her MA and BA at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts. She’s held solo exhibitions throughout Norway and in Holland, Denmark, Sweden and Belgium.

Bill Rodgers is the Managing Editor of cfile.daily.

Do you love or loathe these works of contemporary ceramic art? Let us know in the comments.

Love her work, so clear and poignant. Thank you for bringing her to my attention.