Chinese artist Mo Yi was born in Tibet in 1958. According to his biography at the Walsh Gallery, he began his adult life playing pro soccer in the Chinese League. He produced his first exhibition in 1990 at the age of 32, titled The Great Wall/Great Wall Man, a collection of his photography, record and video work. He used the following three years for self-discovery, at one point returning to Tibet and traveling the Silk Road from Xian to the Great Wall on foot.

The works we’re showing here are indicative of Mo Yi’s reflection on Chinese history and culture, rendered in ceramic tile.

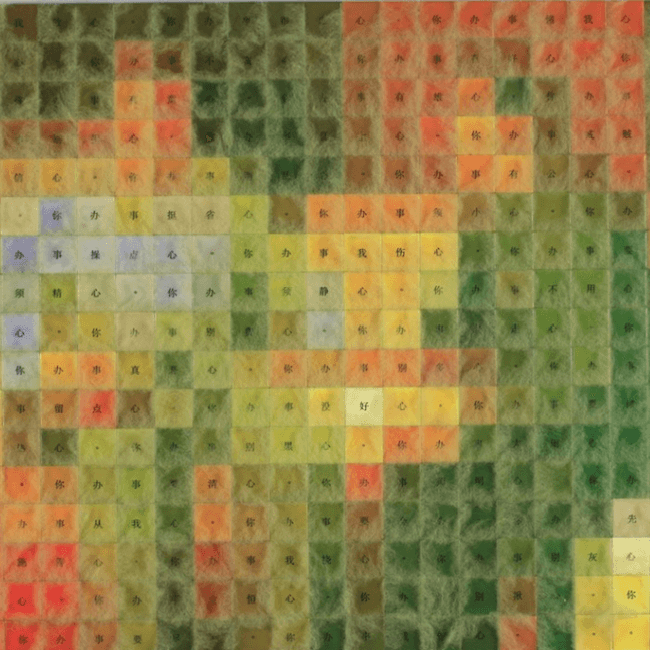

Mo Yi; With You in Charge, I am at Ease; 2011-2013; colored ceramic tiles, wood and threads, 83 x 112 inches. From Contemporary by Angela Li, Hong Kong. Click to see a larger image.

Though they appear to be heavily abstracted up close, the political message clicks into place at a distance. The titles are loaded with propaganda and it feels strange recognizing the part of my mind that can accept the image through all the haze. I feel as though this draws attention to my lack of agency as an individual. It makes me aware that there are triggers in my mind that can be flipped to make me internalize a message without any consent from myself. It turns propaganda into an entity, a sentient idea searching for a back door into my thoughts. I’m aware of being manipulated and it feels extremely uncomfortable.

I wanted a way out and found one quickly. The images turn back into harmless colored tiles the closer you get. Few things can survive scrutiny and that’s actually a comforting thought in this case. You’ll eventually find the zipper if you study the monster’s costume for long enough. The propaganda will vaporize the moment you stop being passive.

Mo Yi ran an exhibition of these at the Contemporary by Angela Li gallery (Hong Kong, May 14, 2014 — June 14, 2014) titled, Illusory Memories. Art Radar states that the tiles evoked images from the Cultural Revolution period in China. The tiles each feature short phrases that compliment the imagery, “for instance, Mao’s famous saying: ‘With you in charge, I am at ease.'” Not to besmirch Mo Yi’s artwork with a reference to pop culture, but reading that I cannot help but think of the scene from the John Carpenter movie They Live, in which the hero puts on the glasses for the first time.

Mo Yi, A Poor Man’s Child Soon Learns to Cope, 2011 – 2013; colored ceramic tiles, wood and threads; 33 9/10 x 28 3/10 inches

There appears to be minimal editorializing from Mo Yi in the series. He speaks with the voice of his subject, skewing it slightly so it can be studied from a new angle. Still, there are choices he made that lead to murkier depths. From Art Radar:

On many of the works, red threads overlap and creep out in between the tiles, depicting red grass which symbolises the vitality of the people surviving through difficult situations. The entire series is bright and colourful, with tendencies towards pop art, but portraying often bleak and complex stories.

In the work Waving, a striking, red image of Mao can be made out as he reviews the millions of Red Guards at Tiananmen Square. Written on the tiles are the names of all those who were killed and persecuted during the Cultural Revolution.

Mo Yi isn’t exposing one kind of propaganda to replace it with his own. Rather, he has a very sober approach to his subject. It’s only by divorcing yourself from the message that you can see the message for what it is. One almost can’t be too invested because that’s an invitation to the slogans, to the idealized imagery. Propaganda takes root in people who would rather feel than think. It blooms into hideous flowers, represented in Waving by the names of the dead.

Bill Rodgers is the Managing Editor of cfile.daily.

Love contemporary ceramic art + design? Let us know in the comments.

Mo Yi, We Must Have a Cultural Army – Red Detachment of Women, 2011 – 2013; colored ceramic tiles, wood, text and threads; 32 7/10 x 43 7/10 inches

Mo Yi, Waving, 2011 – 2013; ceramic tiles, thread and wood, 32 3/10 x 28 3/10. Photographs courtesy of the artist and Contemporary by Angela Li.

Add your valued opinion to this post.