A museum in Seoul, Korea is a brick monument remembering one of the myriad human rights abuses to come out of Second World War. The War & Women’s Human Rights Museum, designed by Wise Architecture, houses exhibitions about “comfort women,” women and girls who were forced to work as prostitutes for the Imperial Japanese Army.

The designers told ArchDaily that their stark gray and black building does not have a “nice entrance,” a lobby or an information desk. This works to eliminate separation between the visitors and the tales of the women who were conscripted. Writing for Human Rights Korea, Yoonyoung Choi discusses some of the exhibitions, notably the faces of women that appear to be coming out of the museum’s concrete walls:

Our self-guided tour started with a short video screening of butterflies (a symbol for freedom from violence and war) continuously fluttering their wings. As a metal door clicked shut behind us signifying the beginning of our main part of the tour, I sensed an immediate change of atmosphere, from those pretty butterflies to faces of old Korean women trying to push through cement to express something they had to suppress for a long time. In a dark viewing room, a testimony of a ‘comfort woman’ named Duk Kyung Kang was shown. One of her famous paintings titled ‘Innocence Stolen’ depicts a Japanese soldier vigilantly watching a weeping naked woman lying under a beautiful cherry blossom tree. As much as I respect that Kang has turned her pain into her professional theme, I could not help but wish that part of history never occurred. We should also note that there are many other elderly Korean women among those who are alive who have not been able to overcome the trauma of the past and live now with disorders related to their experiences.

Through careful design, the architects enhance this dark slice of history. The designers state the building is a “narrative museum” that walks visitors through sequences of memory, healing and records. A small gate at the entrance leads people to an empty room, where they’re compelled to wait for a moment. This signifies the uncertainty experienced by the women who were conscripted by the Imperial Army.

A crushed stone walkway, designed so for its crunching sound, leads to a dark basement with a low ceiling. In this confined space, people hear oral histories from the women.

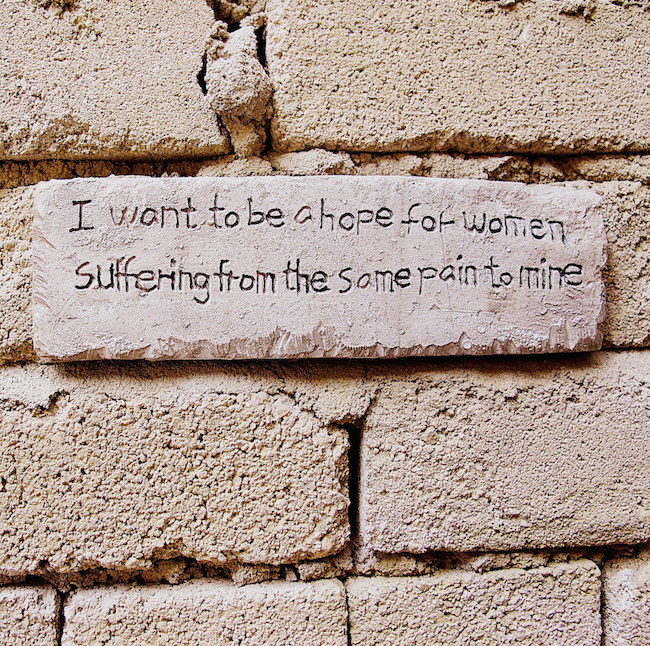

As much of a space for the women as it is for the visitors, the museum becomes complete with final rooms in the sequence which are dedicated to healing. There’s a reception room for the survivors. Visitors can review historical documents here and sometimes have the chance to speak with some of the women. Outside of the building there is a hill of flowers, meant to evoke a peaceful landscape where the women lived as children, it acts as an important counter to the dark brick building and the militant horrors contained within.

Bill Rodgers is a Contributing Editor at CFile.

Any thoughts about this post? Share yours in the comment box below.

Add your valued opinion to this post.