My thanks to ArchDaily for spotlighting Rafael Moneo’s National Museum of Art in Mérida, Spain in their AD Classics series. As much as a fan as I am of Moneo’s talent, this building was a new discovery. Moneo was commissioned in 1979, as part of the Spanish government’s celebration of the bimillennial anniversary of the founding of Emerita, Augusta. It replaced an 1838 museum on the same site, built in the middle of one of the largest and best preserved Roman cities in Western Europe, immediately next to one of the most spectacular surviving ancient theaters in the world. The museum opened in 1986 to critical acclaim.

It is one of the finest contemporary brick buildings to date and an exceptionally sensitive space to show Roman antiquities. Seeing as new museums is the architecture profession’s least successful genre, it is a pleasure to encounter one that is so free of ego and competiveness that too often comes with these commissions. For contrast, I’m reminded, painfully, of a recent extension at the Denver Art Museum, an example of architectural overreach that creates a hostile place for the art to live (or, more often in this case, to die).

There is not an artifact that does feel warmer or richer for it contrast against the brick. And the soaring spaces, seemingly too large, create a sense of a stirring epic moment in time. There is also something egalitarian about the brick and its workmanlike presence that takes away from the austere-white-marble-box-temple-aesthetic so often chosen for museums.

Finally, the building material gives seeming authenticity; it links the art on view with the superb brickwork of ancient Roman builders all over Mérida. Even today “Roman brick” is used as the title for bricks that are based on Roman standards, standards that Moneo has followed in spirit but not stylistically.

The article ArchDaily comments on his imaginative use of use of brick and light:

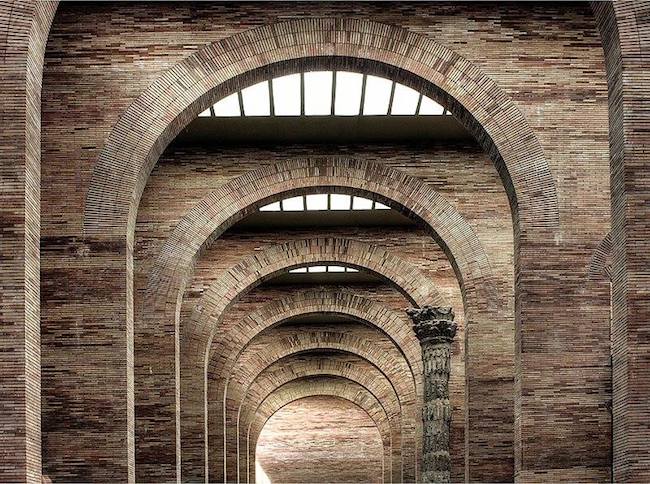

Thin, elongated brickwork, distinctly non-Roman in its shape and perfect uniformity, gives the museum its trademark appearance. Walls, columns, and arches are made of the same material, but the appearance is far from monotonous; patchworks of gold and red hues paint the walls in pixelated clusters of color, lit afire by the dramatic overhead lighting. For Moneo, whose body of work displays remarkable stylistic variation, it is perhaps this careful and deliberate control of daylight that makes this building characteristically his. As Robert Campbell wrote in a Pritzker retrospective of the architect, “the handling of the interior daylight is masterful, here an ever-changing golden wash. The light contrasts with the ghostly paleness, therefore the pastiness, of the antiquities on display.”

Arches have long been used to mark the greatest achievements of Roman civilization. Constantine, Titus, and Septimus Severus built them to commemorate their military victories. Engineers at Segovia and Nîmes incorporated them into their revolutionary aqueducts. And fifteen hundred years after the Fall of Rome, Rafael Moneo gave a modern touch to the ancient structure in Mérida’s breathtaking National Museum of Roman Art, located on the site of the former Iberian outpost of Emerita Augusta. Soaring arcades of simple, semi-circular arches merge historicity and contemporary design, creating a striking yet sensitive point of entry to the remains of one of the Roman Empire’s greatest cities.

The small bricks returned when Moneo was invited to design the extension to the Prado in Madrid. Completed in 2007 it was hugely controversial as Helen Zuber explained De Spiegel.

Moneo has been fiercely criticized for his project, which took six years to complete. The costs soared until they reached the final sum of €152 million ($219 million) — more than three-and-a-half times the original budget. The architect has modestly hidden his creation behind the Prado’s historical wing so that only visitors entering the museum through the back entrance can see it from outside. The size of the Prado has increased by more than a half thanks to the addition of four exhibition halls, an auditorium, workshops facing the cloister and an archive.

Moneo has “distanced himself from the trend towards spectacular buildings” — such as the glass pyramid built in the Louvre’s courtyard in Paris by I.M. Pei or Norman Foster’s sophisticated steel-and-glass addition to the British Museum in London — says Spain’s most renowned art critic, Francisco Calvo Serraller, in defense of the new building. Moneo has found “the most admirable solution” for Madrid, in Serraller’s view, by opting for avant-garde architecture instead of mere imitation.

The building is built with materials, including bricks that were used in the original Prado buildings, and while it has bulk it’s characterized by modesty. It also allowed for Moneo to create a wonderful esplanade of hedges in a cross-hatch maze. Both are high points for brick in architecture and, to bring the inside and outside together, many of the galleries inside have rich brick-red painted walls.

Garth Clark is the Chief Editor of CFile

Any thoughts about this post? Share yours in the comment box below.

The National Museum of Roman Art in Mérida, Spain by Rafael Moneo.

Moneo’s drawings for the Roman Museum.

Add your valued opinion to this post.