Welcome to Part 2 of this month’s Architecture Digest. We had such a bounty of buildings to cover in this issue that we had to split our serving into two courses. In this, the latter half of the meal, you will find more great architecture for your eyes to feast upon. Enjoy!

1 | Museum De Lakenhal

In 2013, Happel Cornelisse Verhoeven and renovation experts Julian Harrap won a competition to simplify the existing museum and add an extension. A challenging task given the building’s rich history. Archello explains:

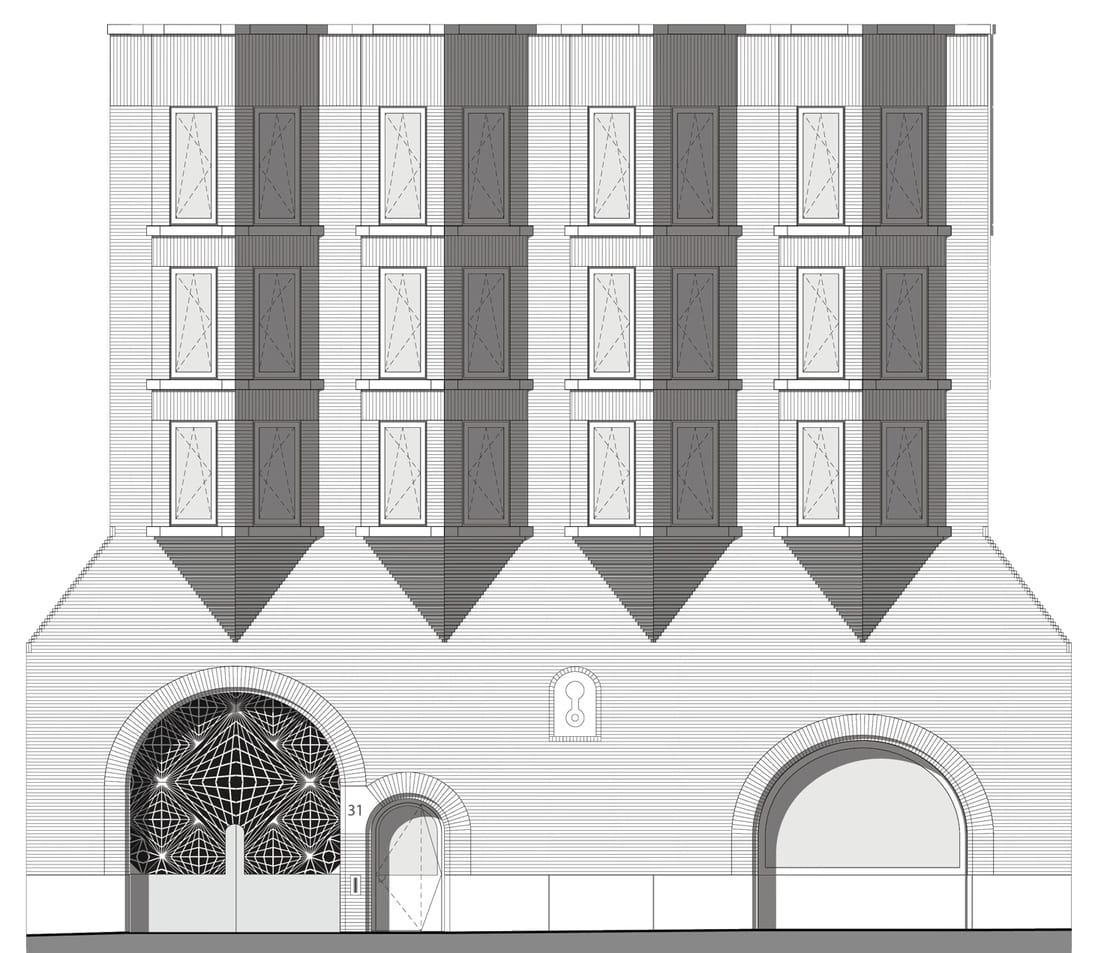

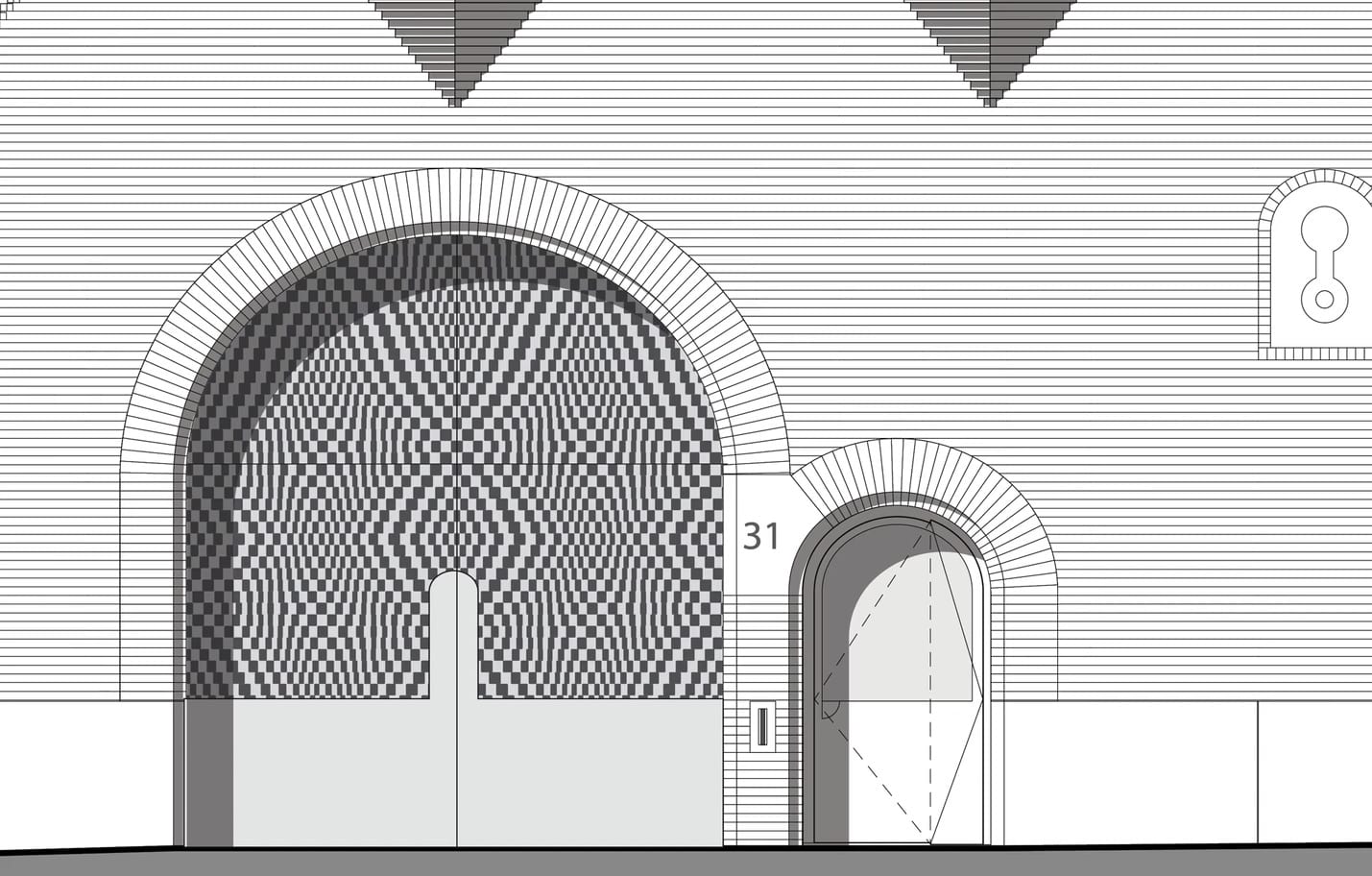

“The Museum De Lakenhal is an arts and crafts museum located in the city of Leiden (NL). Housed in a building from 1641 by city architect Arent van Gravesande, the pragmatic brick building is a fine example of Dutch Classicism and features a subtle brick pattern that refers to the woven fabrics the city was famed for in its trading history. [Hence the remarkable feeling of digital transparency.]

While serving as a connecting, organizing element with new programmatic activity, the extension integrates with the existing museum and is embraced as part of a recognizable, one-piece architectural unit that refers to the large textile factories that stood around the Lammermarkt until the end of the 19th century.”

To see the full power of the new building’s facade look at the drawing in our following album where, when shade strikes triangular windows, defined spear-like columns descend.

2 | Antwerp Fire’s Red Alert

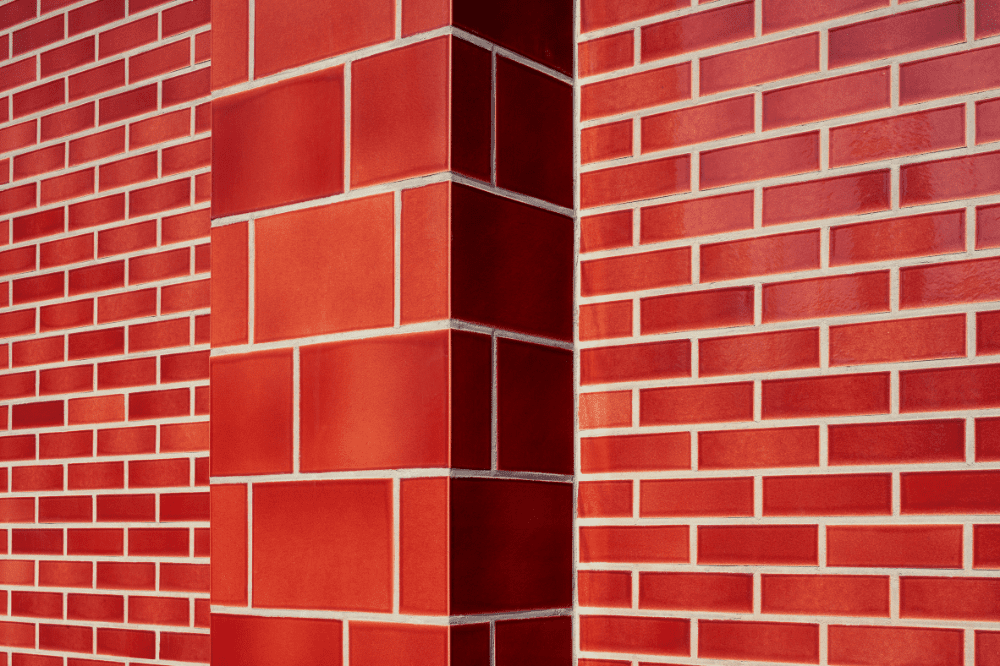

The Antwerp Fire Department inaugurated a new fire station in the Wilrijk district by Happel Cornelisse Verhoeven. The fire brigade is manned 24/7 by successive shifts and provides the accommodation of a depot with fire and ladder trucks, office and living rooms, dressing and sleeping quarters. And what better color for their task, fiery red. Archello notes:

“Particular attention has been paid to the tectonics of the façades that express the typological stacking of the garage, residence and tower. This stacking decreases proportionally in height and is emphasized by a mutual setback of ten centimeters. The pilaster façades are made of red-glazed bricks in large and small formats and are rhythmically interrupted with red-painted cordon bands and deep-purple window frames. The monochrome character provides a recognizable identity in the neighborhood, an “architecture parlante” in which form and appearance irrevocably remind us of the function of the building and the urgency of its users”

3 | 111 57th Street: Getting High on Ceramics

“If the redevelopment of the 1924 Steinway & Sons piano store in Midtown were a song, it would be a long one, with some dramatic pauses and a bit of dissonance” writes C.J. Hughes for the New York Times.

His subject is the latest needle, 111 57th Street that stands 1,428 feet, on the site of the Steinway showroom and store, where legends including Sergei Rachmaninoff once practiced.

Our interest is not billionaires, pianos or Rachmaninoff (maybe a little) but the ceramic cladding that sheathes this building from top to toe. The architects, SHoP state:

“Terra-cotta is one of the most beautiful and adaptable materials available to architects today. For 111 West 57th Street, blocks of sequentially varying profiles were modeled, extruded, glazed, and then stacked into an involuted pattern, like a softly breaking wave, that appears at once novel and familiar. Staggering those elements across the facade creates a distinctive moiré that changes dramatically when seen in different lights or from various distances”.

SHoP wanted to achieve both a feeling of new and old, the latter refers to the city’s glorious history of terracotta clad buildings from the late 19th century to Cass Gilbert’s, Woolworth Building, New York’s tallest building from 1913-1930 (it’s still one of the 100 tallest buildings in the USA). The popularity of terracotta cladding continued into the 1930’s, many classics of which are nearby.

4 | The Lustron Porcelain Home

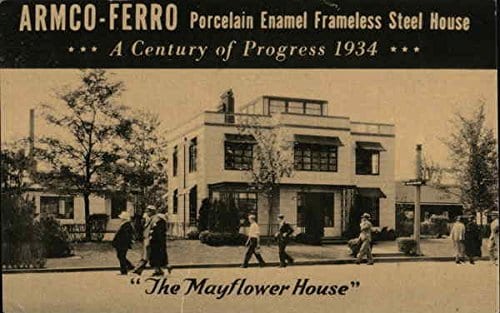

“This is not a grand as the church in Porsgrunn, Norway, but it’s also a tale of porcelain buildings, or to be more precise, houses” Patrick Sisson writes in Curbed explaining their arrival in the 1947:

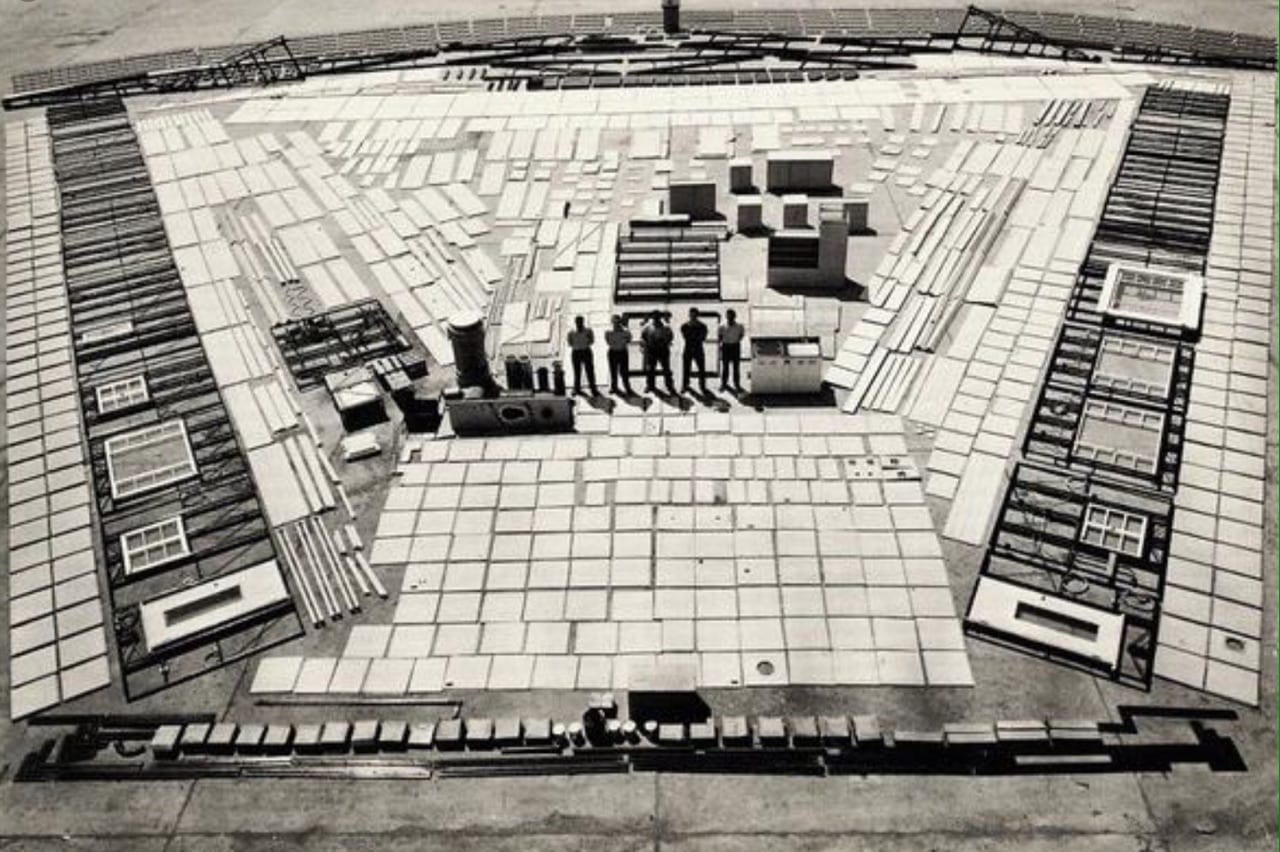

Lustron homes was the brainchild of Carl Strandlund, an industrialist and inventor with the Chicago Vitreous Enamel Corporation who had previously worked on building prefab gas stations. To fulfill his goal of creating homes that would “defy weather, wear, and time,” just as the postwar housing boom was reaching a boil, he took over an old airplane manufacturing plant in Columbus, Ohio, and in 1947, began cranking out prefab home that could be shipped and assembled across the country.

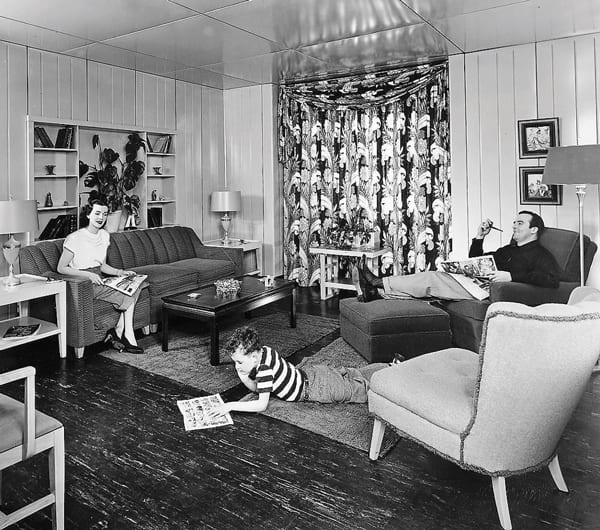

With built-in shelves and pre-installed appliances, these dwellings, ranging from about 700 to 1,140 square feet, were symbols of modern living, delivered as a kit of more than 3,000 pieces on the backs of specially outfitted trucks. They featured sleek exteriors steel walls with baked-on porcelain enamel finishes that were nearly impossible to drill through, requiring homeowners to hang shelving and artwork via magnets (long-lasting and durable, they could also be cleaned with a quick wash and wax).

Learn more in the book Lustron Stories

5 | Surnevik’s All Porcelain church rises from charred ruins

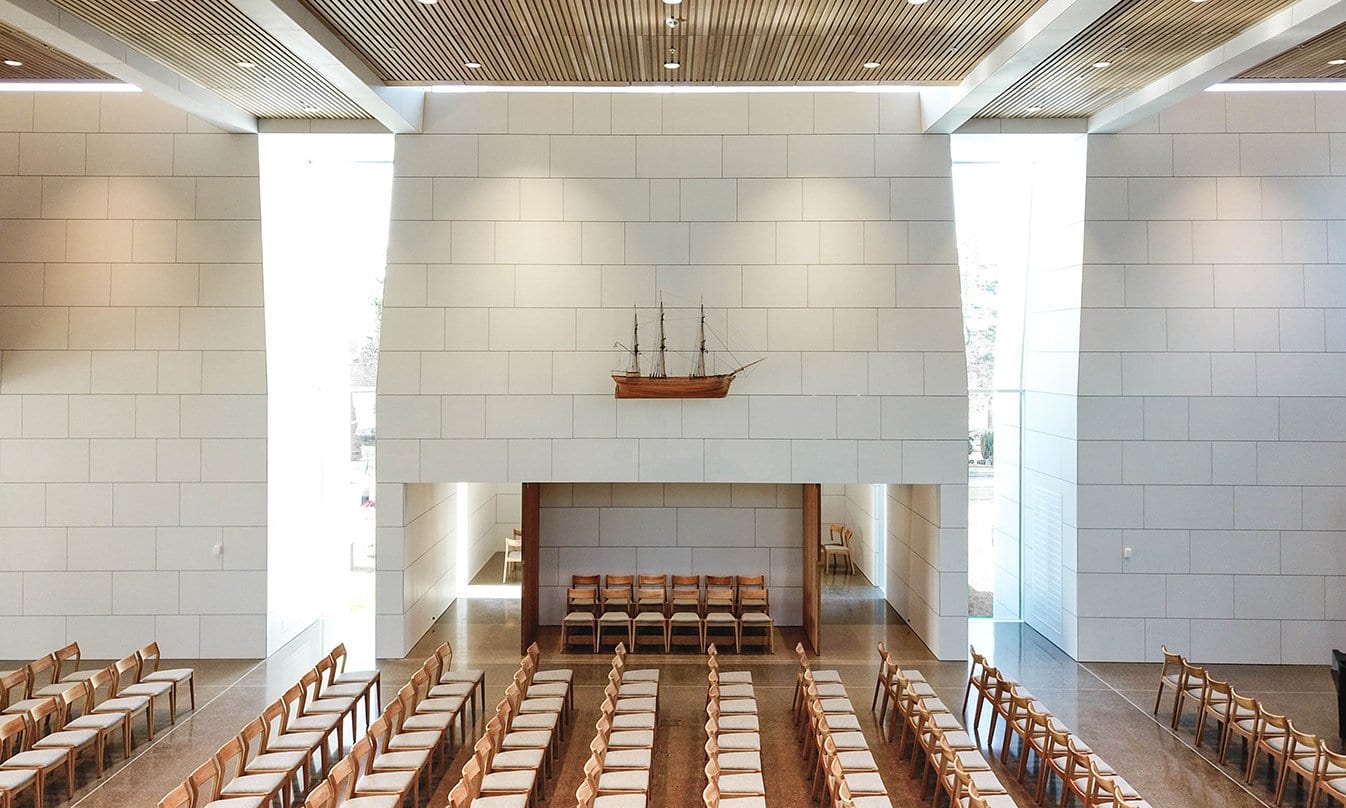

This is somewhat more ambitious compared to Lustron porcelain houses above, but they are cousins somewhat removed. Architect Espen Surnvik’s goal was to was recreate the monumentality, of the old rococo church in the city of Porsgrunn, Norway, but in a totally new way 250 years later. He told Dezeen:

“We wanted to create the experience of something new and extraordinary, in the same way that the elegant old church represented something extraordinary and significant from its age. Porcelain is a fantastic material in many ways, its density is very special and keeps it very clean, by preventing dirt from sticking to the material.

The clean surfaces give the church a kind of purity linked to the liturgy, in the same way that old white-painted traditional Norwegian wooden churches did. After the fire the client had a specification for a more fire-resistant church, so porcelain’s total fire resistance made it very suitable. The entire exterior, and much of the building’s interior is clad in porcelain, a material that was used in manufacture in the city throughout the 20th century.”

6 | Dancing Arches

The School of Dancing Arches by Samira Rathod Design Associates is a collection of small spaces with irregular shapes that encourage play and imagination. Located in the village of Bhadran, in the state of Gujarat:

“The building sits on a plot surrounded by tobacco fields, one of the main industries of the area. The school evolved as a quilt of many small events, of small spaces to hide, collide, climb, roll, run into and out of, to satiate curiosities of a forming mind, allowing its idyllic imagination and wonder,” says Rathod, “a school where the play of hide and seek is perpetual.”

Classrooms are sky-lit and the walls, floors and roofs are entirely clad in terracotta bricks sourced from a klin factory close to the site. Light is designed as to define moments in the experiencing of architecture, with dark shadows in the corridor. Throughout, terracotta has been used as the primary material for bricks, roof tiles, floor and other finishes, to unify the whole project.

“Sourced from a kiln close to site, it is a love of labor from the town and the craft they bring with themselves that lends the building its immaculate semantic and precision,” says Rahtod.

Love or loathe this double edition of our Architecture Digest from the world of contemporary ceramic art and contemporary ceramics? Share your thoughts in the comments section below.

Very enjoyable post – the porcelain buildings were especially interesting