Forty-eight year old Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena was just awarded the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s highest honor. Given our fascination with both ceramics and brick in architecture, we decided to review some of Aravena’s contributions to the field. As it turns out, he’s one of the masters of brick architecture working today.

Aravena was born in Santiago and studied architecture at the Universidad Católica de Chile in 1992. He established his own firm two years later. From 2000 to 2005 he was a professor at Harvard University. There, he founded “Elemental” with engineer Andrés Iacobelli. Elemental is a firm that focuses on social impact, often working closely with the public and end users. Aravena was a member of the Pritzker Prize jury from 2009 until last year.

Tom Pritzker, chairman and president of the Hyatt Foundation, which sponsors the Pritzker Prize, announced the award January 13. Aravena will be recognized at a special ceremony at the United Nations Headquarters in New York on April 4. Aravena is the 41st Pritzker laureate.

In his announcement, Tom Pritzker cited not just Aravena’s design, but also his conceptual practices that address problems unique to current issues. Elemental is known for its experimental approach to building projects in low-income communities. Pritzker states:

“The jury has selected an architect who deepens our understanding of what is truly great design. Alejandro Aravena has pioneered a collaborative practice that produces powerful works of architecture and also addresses key challenges of the 21st century. His built work gives economic opportunity to the less privileged, mitigates the effects of natural disasters, reduces energy consumption, and provides welcoming public space. Innovative and inspiring, he shows how architecture at its best can improve people’s lives.”

We’ll have more on the social aspects of Aravena’s work in a moment. When we heard of the announcement we pulled up some of Aravena’s buildings to look for ceramics. Tile cladding did not seem to interest him but— as luck would have it— we also love brick at CFile. Below are some selections from Aravena’s brick portfolio, some of which are still only renderings (which makes them all the more exciting).

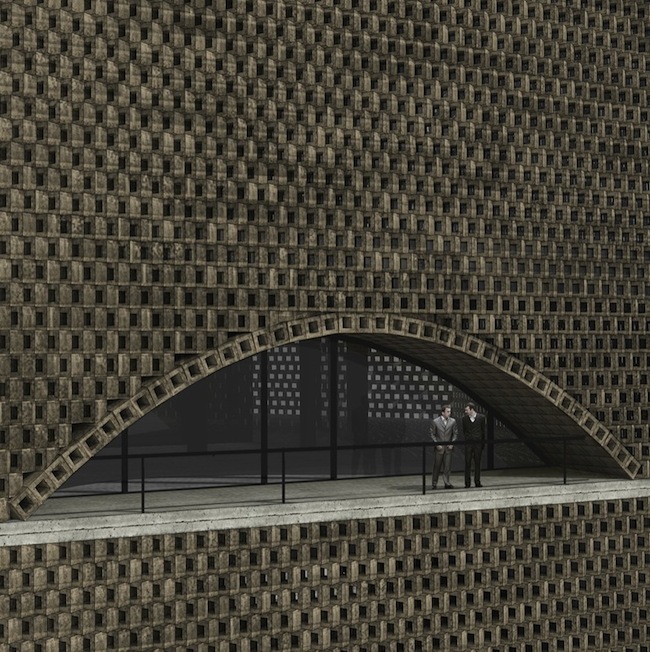

The Tehran Stock Exchange (with VAV Studio)

Aravena and VAV’s project for the Tehran Stock Exchange was selected in a juried competition from among 29 other firms in 2012. We ran a few images from the competition about a year ago, with a focus on Hans Hollein’s submission. Here, we’ll devote some more space to Aravena’s monolithic work, a very tangible cornerstone of economic activity in the region. The images we have here are from Aravena’s renderings of the proposal. ArchDaily described the work when they announced that it had been selected:

(It) was the only project which took into consideration functions and forces, geometry and geography, and an organization that distributed its program in a field condition, evenly spreading its function to best capture, light, views, cross ventilation, as well as shade. In turn, it produces a timeless (yet fast-paced) character of the stock exchange as an institution, a building that extends broader traditions while mirroring the current state of its country.

The selection of the jury was only a suggestion to the client. We haven’t seen any articles saying that ground was broken on the minimal tower, but we’ll keep checking back.

The Tehran Stock Exchange proposal by Alejandro Aravena Architects and VAV Studio.

Photograph by Roland Halbe.

The Universidad Católica de Chile Medical School

Located at the site of Aravena’s alma mater, the Medical school challenged the firm to build classrooms and auditoriums in what the architect called “a dense context.”

“The only way out was to go high,” Aravena said. “Given that massive student occupancy in higher floors has always been hard to solve, we decided to bring the courtyard closer to each upper floor. This building is a vertical cloister.”

The medical school was the his second project at the school. His first (indeed, his first project as an architect) was a mathematics building in 1998, according to The Guardian. The medical school was followed by an innovation center, which is one of the most frequently-posted pieces of work from Aravena’s studio.

Note how the brick is in contrast to the solid facade of glass on the other side.

The Universidad Católica de Chile Medical School by Alejandro Aravena. Photograph by Roland Halbe.

Ordos 100

Ordos 100 is a development in Inner Mongolia, China that consists of 1,000 square meter villas designed by 100 architects from 27 different countries. The builders were selected by Herzog & de Meuron over a master plan curated by Ai Weiwei (it’s a small brick and ceramic world).

Aravena argued that there are two strategies to follow when dealing with large-scale landscapes: “to define a limit and domesticate the space within (introversion) or to gain height to dominate the vastness (extroversion). We decided to do both and have a smooth transition from one to another.”

The brickwork rendered here recalls the Tehran exchange we posted earlier (or, rather, Tehran recalls Ordos, which is the older project of the two). The brick studies are illuminating in this regard. We like the volumes adorning the top of the building, especially the angular one. You can see a similar theme at work on a larger scale with Siamese Tower.

Aravena was joined by Ricardo Torrejón and Victor Oddó, who both did the renderings for the project.

Brick study for the project.

St. Edward’s University Residence and Dining Hall

The hall, built in 2008, fits 300 beds with room for socializing and services within a narrow lot. Elemental did three things:

“We created a plinth using the more public facilities to activate the ground floor, we carved the volume’s core and placed there the social areas and we articulated the perimeter of the building as much as possible, increasing the linear meters of façade in order to guarantee views and natural light to each room. To be able to resist a tough environment, we opted for a sequence of skins that are hard and rough in the outer layer and become softer and more delicate towards the core.”

The hall has some surprises for us. Volumes become more obtuse as the building rises. There is also the L-shaped volume that hints at an inner walkway of glass and red walls, as though the brick building has a candy center.

The St. Edwards University residency dining hall in Austin. Photographs courtesy of the firm. Photographs by Cristobal Palma.

Photographs courtesy of Elemental.

Novartis Office Building

Novartis, a building currently under construction, is for a pharmaceutical company in Shanghai. The report from the Pritzker Prize explains the building’s goals:

The Novartis Campus Shanghai seeks to provide spaces that encourage knowledge creation. The office spaces are designed to accommodate the different modes of work — individual, collective, formal and informal — and foster interaction between the users. Around a forest of Metasequoias, the ground floor accommodates the Fitness and Be Healthy Center which are part of the campus public level where users from the different buildings meet. The outside of the building responds to the local climate with a solid facade of reclaimed brick facing south, east and west. On the north facade, the building is open to let indirect light get inside the open office spaces.

We recognize familiar notes in Aravena’s work. He returns to us with the dark brick and the angular and curving gymnastics that make the building appear monolithic, but not without a soul.

ArchDaily Interviews Aravena following the Pritzker Prize

We mentioned earlier that Pritzker selected Aravena for more than just his sense of design. He’s not cloistered in his practice. Architecture can be syncretic and that comes out in this interview with ArchDaily. Aravena is drawn to using the tool of architecture to address complex socioeconomic realities. To Aravena, architecture is a lever that can move the human beings that occupy architecture in a positive direction. His thoughts are abstracted in the above video, but it serves as a prologue for his TED talk linked below.

Alejandro Aravena’s TED Talk: Involve the Community

Aravena begins his TED talk by recalling a statement he made in the first video: that architecture is most powerful in synthesis with complex reality. His approach to improving quality of life through architecture is summarized in black-and-white terms with an equation he scrawls on a chalkboard. In a way it’s an ominous equation: it symbolizes the trend of people moving into cities and if it’s not addressed adequately those people will be living in slums. That’s where architecture comes in. The lever. Aravena tells his famous “half-a-house” story here.

Aravena was hired for a public housing project in Chile. Faced with a shortage of money and a shortage of real estate in an inverse proportion to the number of families he had to house, the studio was looking at the possibility of cutting living space for each family in half.

Lateral thinking is like a magic trick and Elemental came up with a doozy: build a home in half the space, then give the families enough space to expand on their own. If that seems like a cop-out, remember that the project means that the community remains connected as people expand. The project is also located so that families are close to their place of work, which means that living more comfortably is cheaper and easier than it would be otherwise. The solution satisfies all the constraints while cleverly avoiding the assumed (and worst possible) outcome.

And that’s just the first part of the video. More magic tricks follow. We hope to see what else is up Aravena’s sleeve in the future.

Bill Rodgers is the Managing Editor of cfile.daily.

Love Aravena’s contemporary brick architecture? Hate it? Let us know in the comments.

Alejandro Aravena

such an inspiration to the architecture community…makes me feel part of it,

in his footsteps