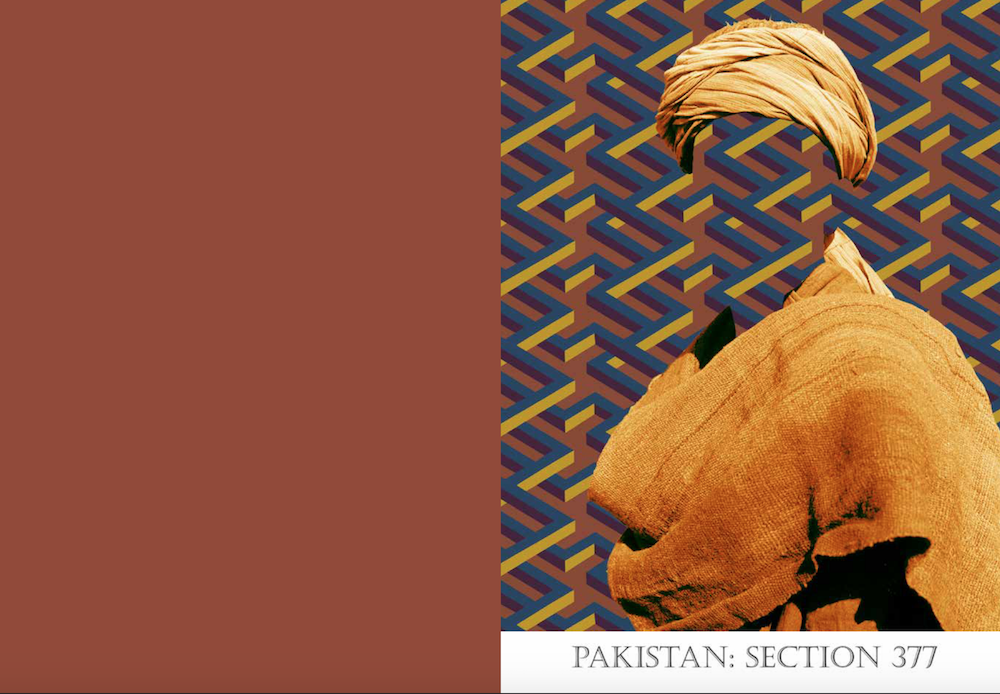

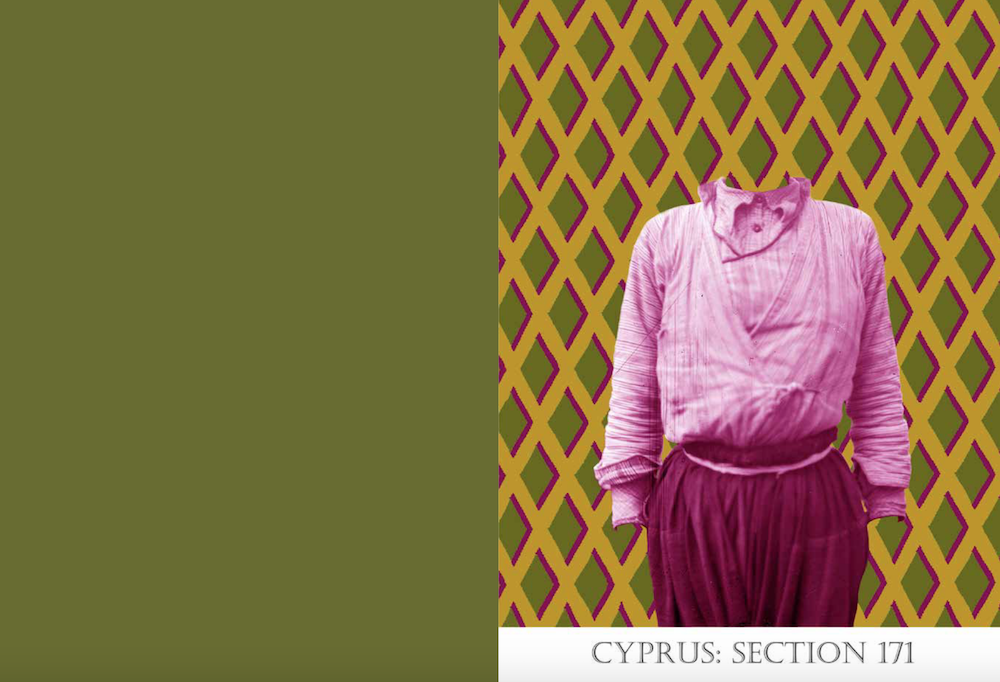

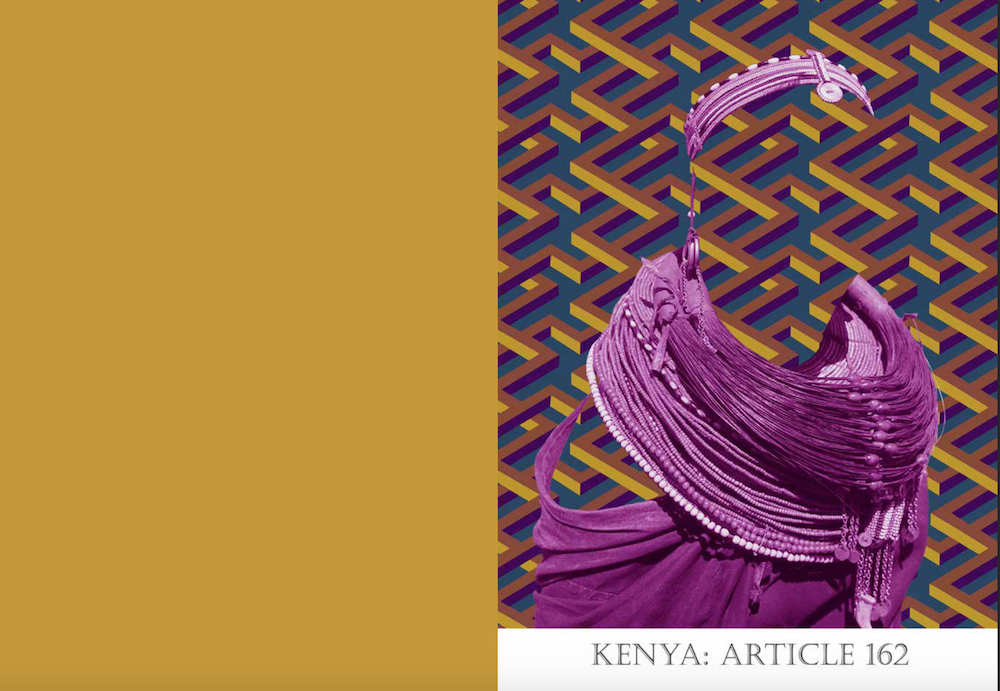

Oxford, UK–Matt Smith is one of ceramics most gifted polymaths. His exhibition Losing Venus, (March 4 – November 29, 2020 and extended to March 6, 2022), consisted of multiple installations at the Pitt Rivers Museum, highlighting the colonial impact on LGBTQ+ lives across the British Empire and sought to make queer lives physically manifest within the museum. From 1860 onward, the British Empire criminalized male-to-male relations, imposing lengthy prison sentences, and the legacy of these legal codes lives on.

Of the 72 countries in the world with anti-gay laws, 38 of them were once subject to British colonial rule. Responding to these colonialist gender laws, Losing Venus seeks to place contemporary discrimination, which is still affecting the lives of many around the world (Cfile’s recent feature on Leilah Babirye visits a contemporary consequence of these rules), at the heart of one of the cultural centers of the country which exported it, examining their impact through the lens of sexual identity and gender fluidity.

The title is a reference to the idea of love and gender, but also references the purpose of Captain James Cook’s voyage in 1768– to measure the transit of the planet of love, Venus. The installation comprises four main parts located on the busy, bazaar-like Lower Gallery (first floor) of the Museum; The Prints (Bow-Fronted Case), The Dolls (Puppet Case), The Banners and The Cook Service (Didcot Case) which is the main focus of this post.

Do download the book that accompanies the exhibition, it is essential to comprehending the depth and perspicacity of this show.

To offer more perspective on this fascinating exhibition Garth Clark and Matt Smith spoke:

Was the cathedral space reinstalled for your show or were the only changes making space made for your art to be included?

The cathedral space was not reinstalled, and one of the biggest issues was working out how to create an exhibition in a space that was already jammed full of objects. The case with the ceramic plates and the one with the dolls are often used for temporary displays. The wall with the screen prints is actually a false wall erected in front of a wall of kites and other objects – it was decided that this created less stress on the objects than taking them off display. The two large banners were custom made for the space – I ended up printing on a mesh that is used to hide scaffolding rigs on building projects – I wanted a material that could be seen through and allow light through…and I also liked the metaphor of the ethnographic museum being under reconstruction.

Was the Cook service the genesis of the exhibition? Was the initial show less ambitious than it became?

The question about the Cook service is a really good one. I find the idea of colonialism so complex and multifaceted that it seemed logical that any response to it would also have to be layered and multifaceted. The starting point for me, for the show, was seeing a map of the British Empire in the 1920’s placed next to a map where it is currently illegal to be gay, which lead to me investigating Cook’s voyage to Tahiti, and BINGO, found out that he was traveling in order to map the Transit of Venus….an expedition to understand the movement of the goddess of love.

The Screenprints developed at the same time as the Cook Service – the photographs are one of the few places that people – rather than clothing and objects – are still present in the museum. The gridded background used by Victorian photographers visually mapped with textile works I have been doing, and speak to the museum’s ability to collect, catalogue and show material culture, but all too readily erase love and lives lived. So, in answer to your question, the show really came about a whole – very much a direct response to the absence of LGBTQ lives in the ethnographic museum, and an unpicking of any Western notions of the West being more tolerant of LGBTQ lives than other places in the world.

What are the sources for imagery on the service plates. European classical art is clear but where did the more eccentric images come from?

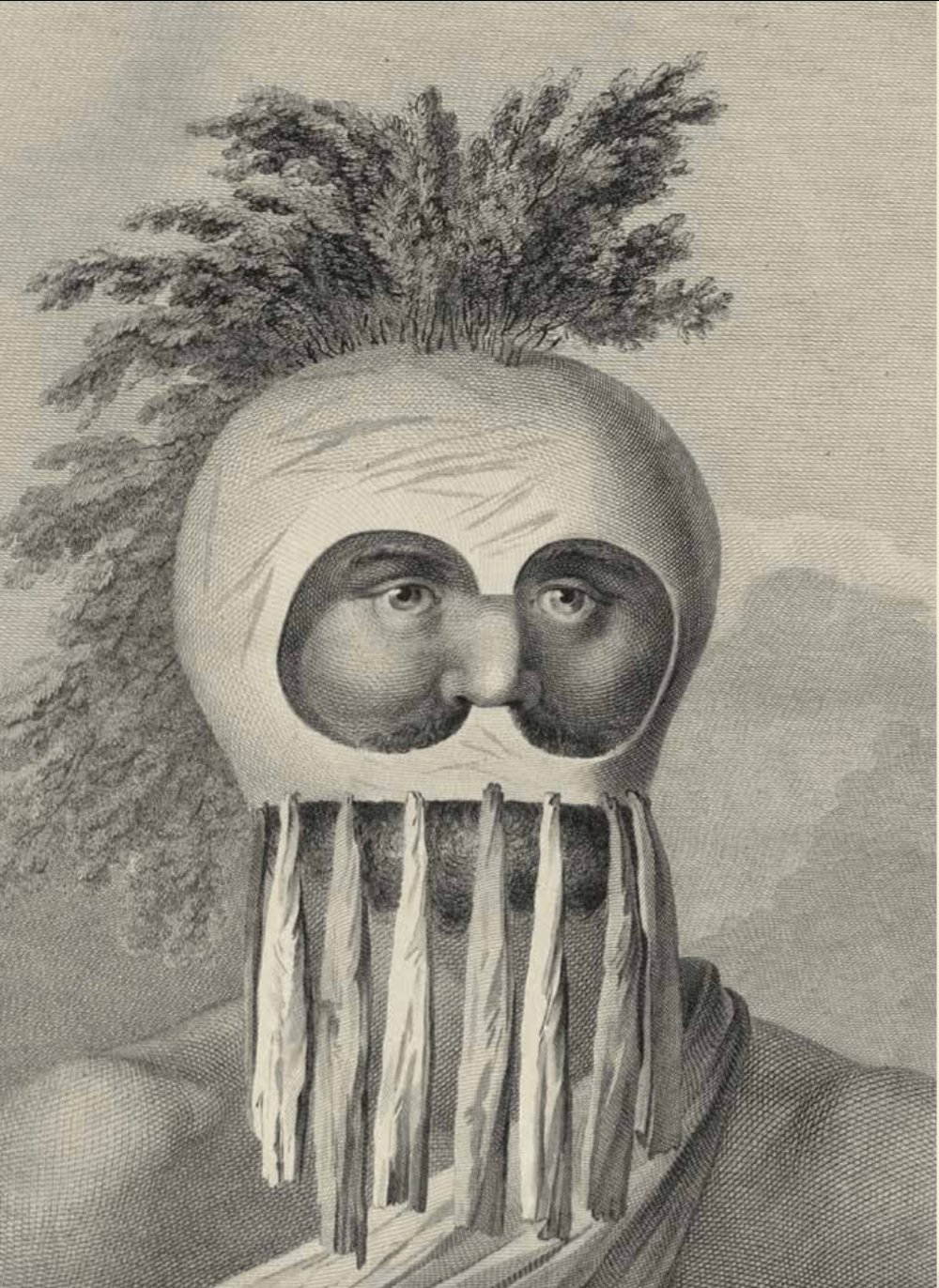

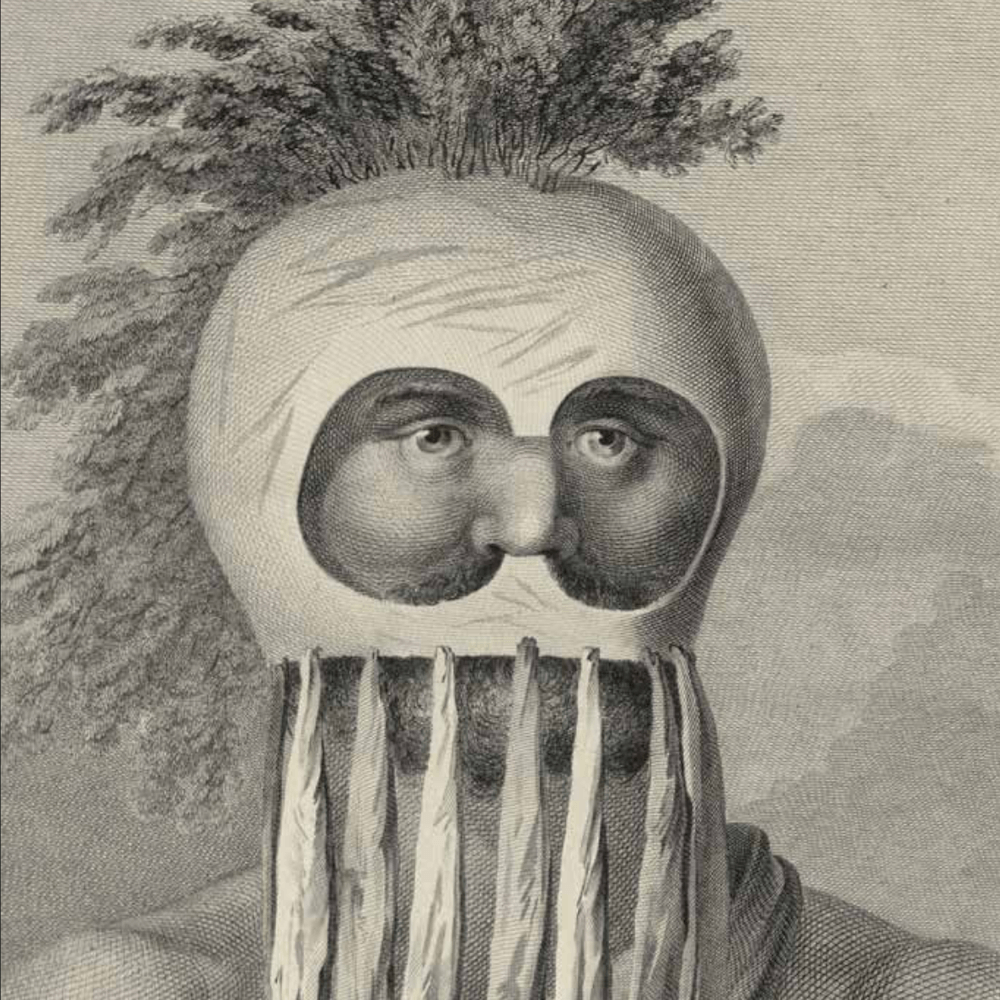

The plates use two sets of images – the pink images are all European images of Venus, the goddess of love. The brown images are all taken from the “Atlas to accompany Captain James Cook’s account of his voyages to the Pacific Ocean in the years 1886-1780” held in the Met Office and Archive. The book is a series of prints based on drawings made by botanists and crew on Cooks’ voyages. The pink images are overlaid onto the brown images – European myths obscuring and hiding scientifically recorded ways of being/living and loving in the South Pacific. Again, I wanted to question European enlightenment notions of western scientific truth vs non western ways of understanding, living and loving; and visually represent the epistemicide (destruction of existing knowledge) that occurred as Western ideas of sexuality erased non western ideas.

In a way, I was looking for (queer) love in the museum, and trying to work out why it was absent. It’s argued that mourning is love with nowhere to land, so the iconic Chief Mourner’s costume from Tahiti, which is in the museum (and was collected by Captain Cook) was a natural jumping off point

Hope that helps, it’s quite a dense show to unpick.

C-File has been invaluable for me to keep up with developments in the ceramics world… and elsewhere. It has been an irreplaceable tool, and I’m saddened to see it go. But everyone must move on, right? I wish both of you the best in all your future ventures.

Bruce

Garth & Mark,

Thank you so much for your many years of thoughtful work!

It has been a delight to receive the global perspective of Cfile these past many months when at times it has felt that we would never again freely roam the world looking at art.

I wish you both a creative happy & healthy 2022!

Suzann