Dr. Odoh’s essay accompanied Kó gallery’s solo exhibition by Ngozi-Omeje Ezema’s Boundless Vases, the first of a three-part exhibition series in which the New Nsukka School re-examines the conceptual and material practices that characterize the art department at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

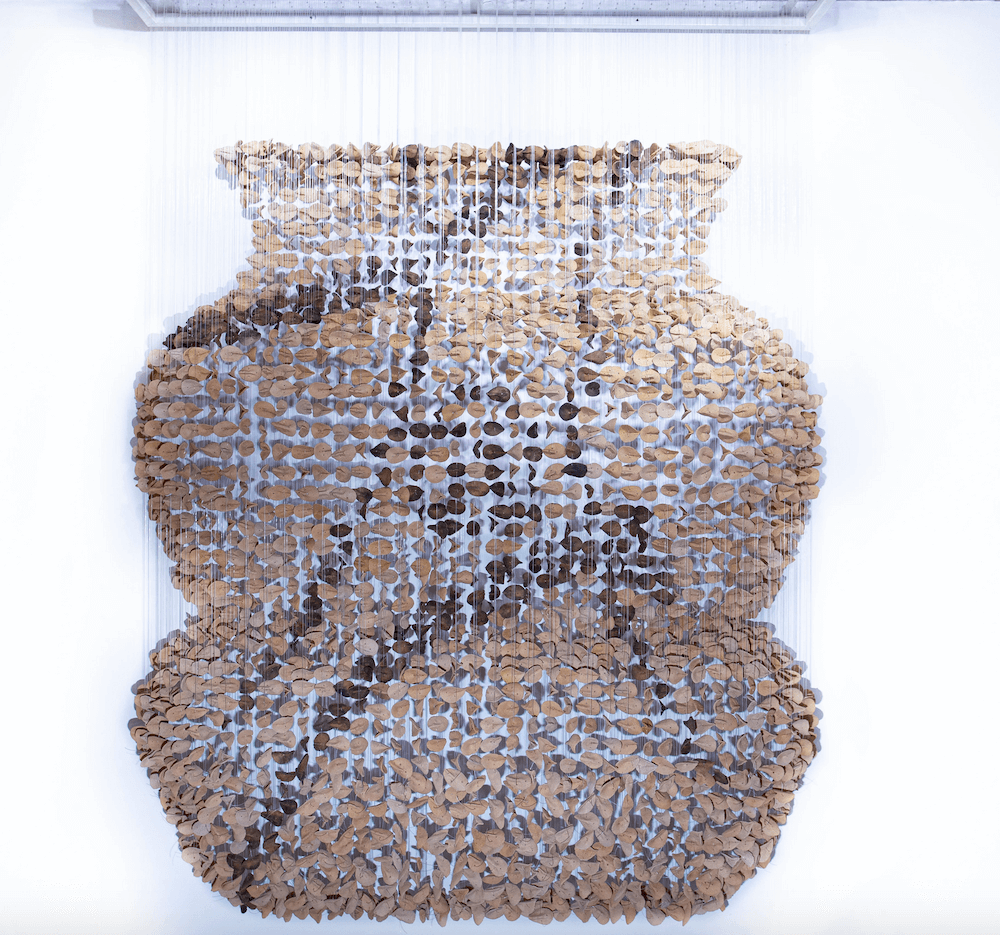

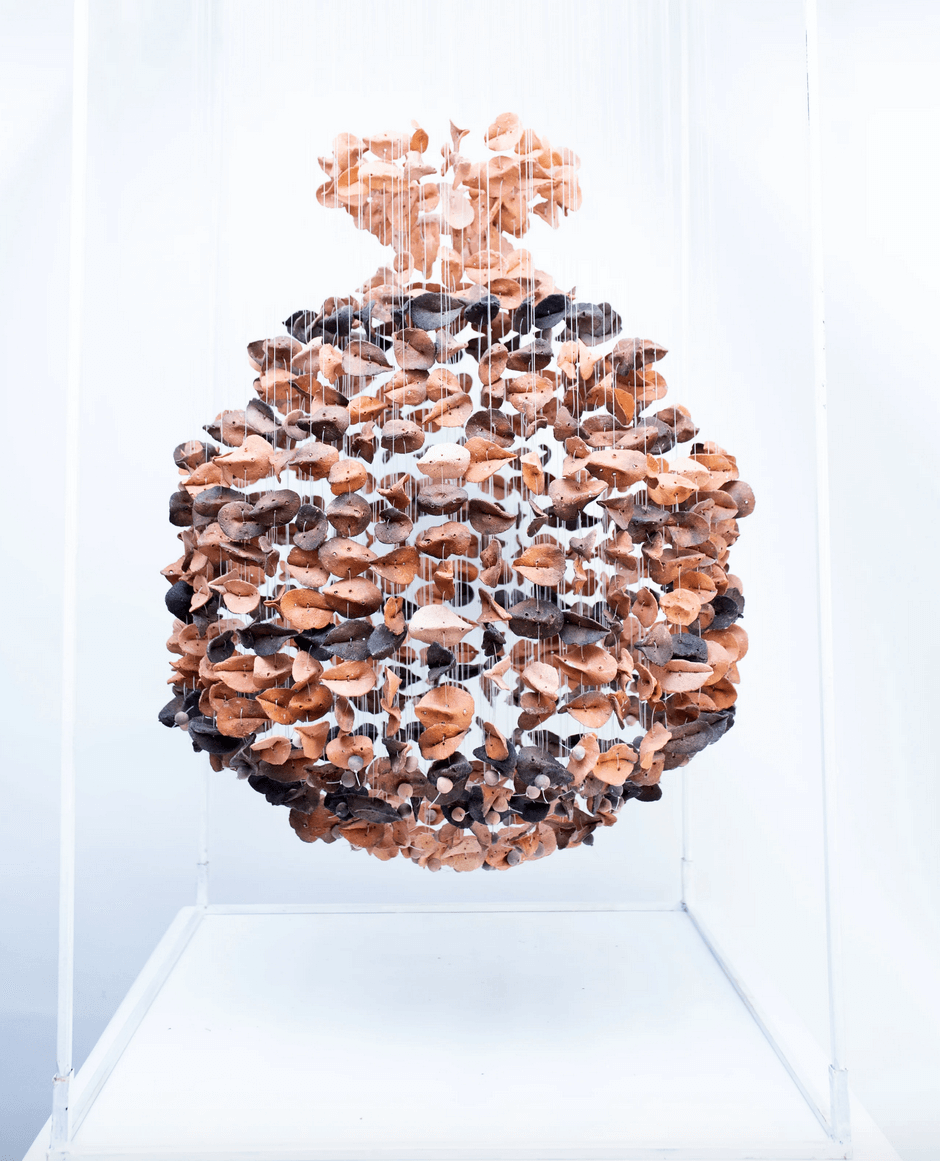

Vase #1

2021

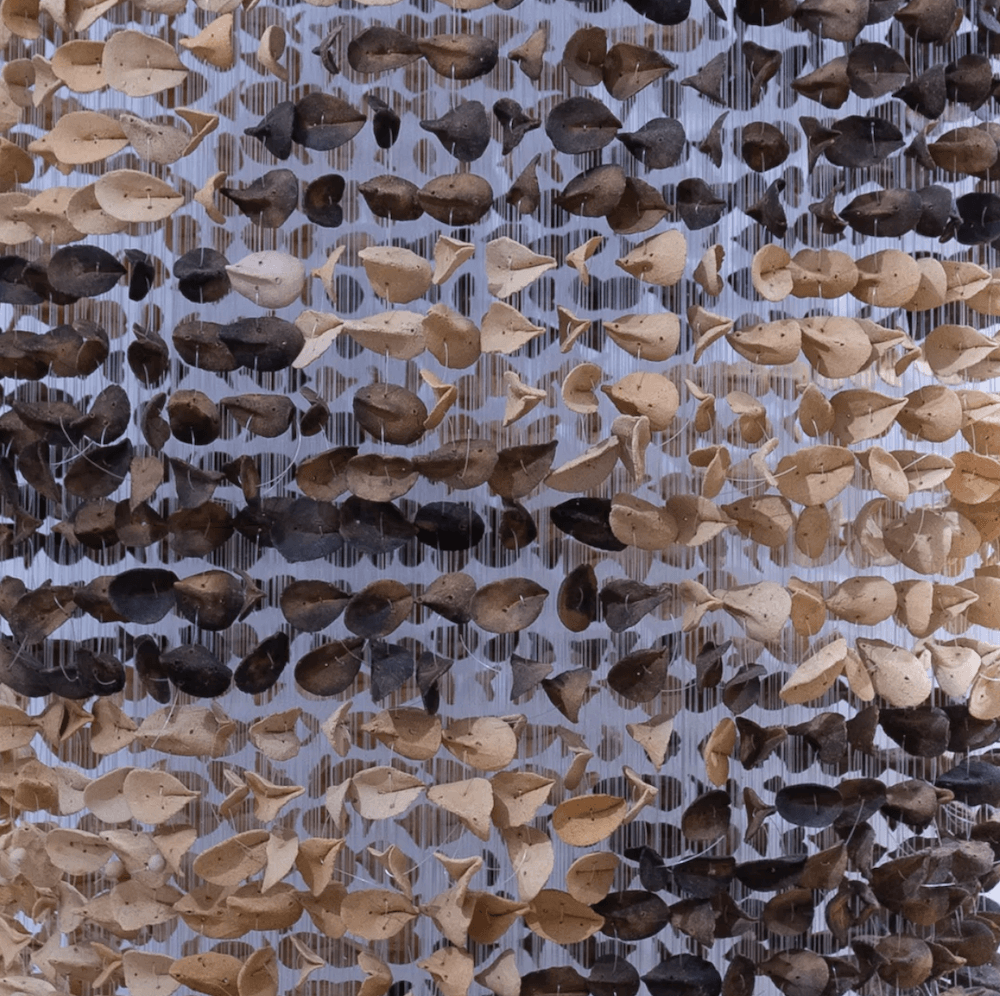

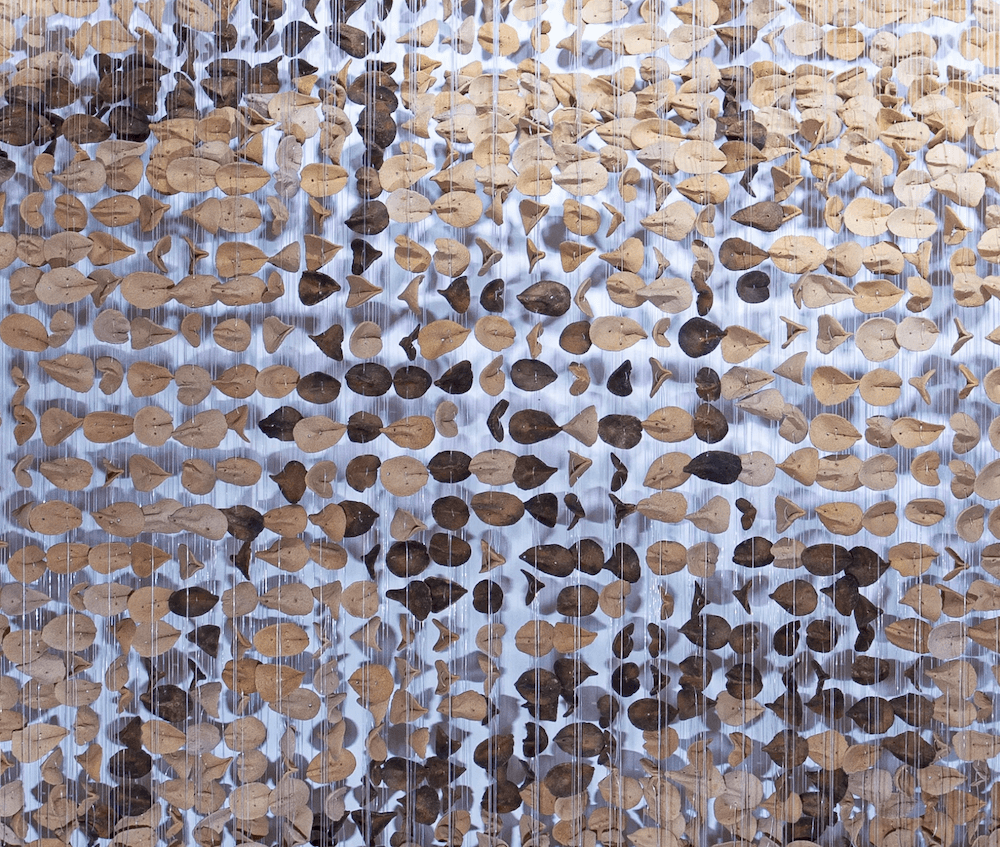

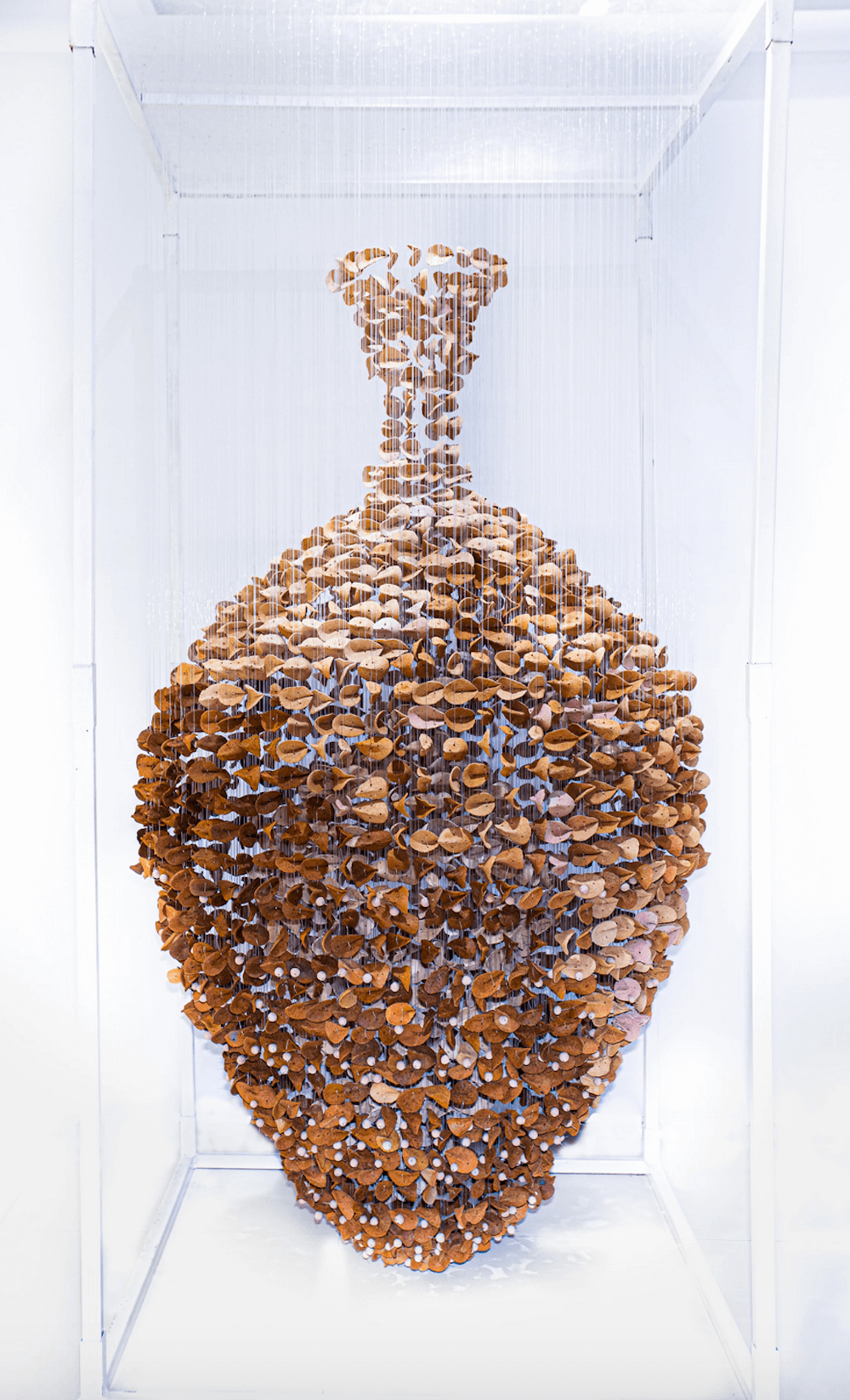

Like joyful music locked in the sensuous embrace of its stringed sanctuary, Ngozi-Omeje Ezema’s recent ceramic art installations evoke imageries of a well-orchestrated symphony in which hundreds of suspended terracotta leaves construct the musical notes of its harmonious melodies.

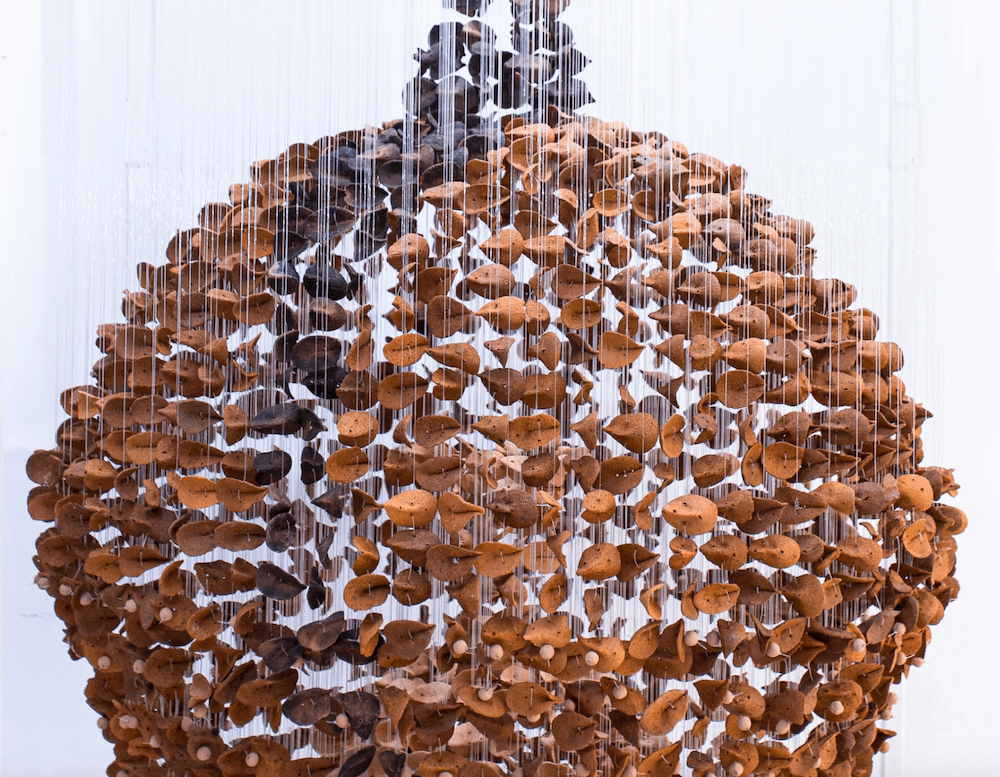

Ezema’s Leaf series highlights her ongoing exploration of the leaf motif as an expressive visual element rich in affective metaphors. For the artist, the leaf motif represents a state of being; a transient element whose materiality symbolically dramatizes rites of passage and its associated conditions of liminality. In her recent works, the material properties of leaves are used as formal and narrative handles to address issues relating to womanhood.

In its congregated and suspended state, the leaf motifs act as both the messenger and the message. They not only simulate forms, they also disrupt, define and activate spaces. Ezema’s installations can quickly shift from a state of stasis to that of dynamic movement. They also project a radical aesthetic that draws attention to infinite possibilities riding on the wings of experimentation.

Union I, from the Leaf series

2020

Ngozi-Omeje Ezema represents the new generation of contemporary Nigerian ceramists who infuse modernist sensibilities into an age-old traditional art form. Her approach to the clay medium mirrors the footsteps of other Nsukka trained ceramists like Chris Echeta, Ozioma Onuzulike and Caius Onu, whose works radically challenge long established notions that locate ceramics art within the limiting frame of its utilitarian function.

Ezema trained as a ceramic artist at the Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. In 2009, the same year she completed her Master of Fine Arts (MFA) programme in ceramics art, she was offered a teaching appointment at the Nsukka art department. For the past decade, she has combined art teaching with a vibrant studio practice. Ngozi-Omeje’s training at the Nsukka art department strongly impacted on her artistic development. Her exposure to the culture of experimentation and exploration which drive the creative philosophy of the Nsukka art department opened up her mind to the possibilities of creating art using unconventional methods and commonplace materials.

Also, her pedagogical experiences with seasoned ceramists like Ozioma Onuzulike and Vincent Ali, who taught her at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels, played key roles in shaping her artistic sensibilities. On a more profound note, Ngozi-Omeje acknowledges the influence of El Anatsui on her art.1 Anatsui is unarguably one of the most prominent and most influential artists of the Nsukka art school. His art practice has had a proselytizing influence on several generations of artists who trained in the Nsukka art department.

Anatsui’s occasional visits to Ngozi-Omeje’s studio provided invaluable creative stimulus that significantly benefitted her studio processes. For instance, in her installations, we find resounding echoes of the technique employed in El Anatsui’s bottle top installations, which entails using multiple units of a material in ways that aim for the “aesthetics of the critical mass.”2

Although Ngozi-Omeje has explored unconventional methods that upend traditional use of the clay medium, her suspended ceramic art installations, a compositional strategy which she first explored during her graduate studies, have become her trademark signature style. The art of suspending objects in space has been critically explored by numerous artists. Alexander Calder is considered a pioneer in this field, having begun hanging art as far back as the 1930s.

Notable suspended sculptors whose works may have inspired Ngozi-Omeje include Jae-Hyo Lee, who composes works of astonishing scale and beauty using rocks suspended with strings, and Sean-GhiBahk, who has extensively worked with charcoal. Omeje has created quite a number of works using the suspension technique. These include Up and Down ( 2009), Fishers of Men (2009), Imagine Jonah (2009), Think Tea, Think Cup (2010), She Bleeds (2010), Life on Strings (2011), Placenta (2014), Against all Odds (2015) and In My Garden there are many Colours II (2016).

Stunted, from the Leaf series

2020

In 2018, she undertook her most ambitious installation project so far. The installation comprised a herd of nine elephants which the artist used symbolically to memorialize personal experiences. Eight of the elephants represent the living members of her family. The ninth elephant, separated from the group but still watching over them, alludes to her departed father, whose accomplishments, personal traits and titular name find figurative endorsement in the attributes of an elephant.

In Ngozi Omeje’s Leaf series, the leaf motif — which the artist used as a modular design element in her elephant project — is again deployed as a critical tool for advancing the formal, aesthetic and thematic geographies of her art. In the artist’s words: with respect to the varied tones of the terracotta leaves which comprises off white, light brown reddish brown and dark brown tones, the artist explains that the tones are achieved by firing the clay forms at different temperatures.3

Very dark tones are produced by covering the bisque fired clay forms with sawdust and setting it on fire. The stringing process is carried out in a methodical manner. Using multiple strands of suspended fish line, hundreds of perforated leaf motifs are stringed together at predetermined levels and positions to simulate vases of different shapes and sizes. In contemplating her suspended vases, our experience and understanding of what a vase is and the function it performs, are radically subverted. Her works are structurally dynamic.

Vase #16

2020

Subjugation, from the Leaf series

2020

At the slightest disturbance, the suspended vases can shape shift and are also capable of producing musical sounds as the terracotta leaf forms make contact with each other. In addition to her installations that allow for three-dimensional viewing, Ngozi-Omeje also explores works that could be mounted on the wall. This adds a new dimension to her compositional structuring and expands the contexts in which her works could be viewed and experienced. Beyond its aesthetics, Ngozi-Omeje’s suspended vases are infused with a social vision that interrogates the gendered landscape of her cultural environment.

The burdens that women bear in relationships, their physical attributes — as well as experiences that define their position in society — are symbolically wrapped around the physical and functional attributes of a vase. In the works Subjugation, Freedom and Extinction, the structure and placement of the smaller vases contained within the larger vases articulates Omeje’s visions of womanhood. Ideas relating to motherhood, subjugation, oppression, indifference, conflict, resilience, resistance, togetherness and freedom are framed using a formal language that is as sensuous as it is evocative. In engaging Ngozi-Omeje’s recent body of works, we are made to experience the passion, industry and experimental energy which she invests into her art.

We are equally drawn into an environment that reveals in an ennobling manner the seamlessness and awesomeness of artistic imagination. Borrowing from Sylvester Ogbechie’s characterization of Nsukka School art, Ngozi-Omeje’s art projects a radical aesthetic that speaks the “language of sublime awe.”4

Dr. George Odoh is a Senior Lecturer in painting and drawing in the Department of Fine and Applied Arts at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

1.In my interaction with Ngozi-Omeje Ezema during a studio visit, she recounted the many roles that El Anatsui played in advancing both the conceptual and experimental components of her art.

2.Ozioma Onuzulike used the term ‘aesthetics of the critical mass’ to describe how Nsukka artists assembled individual pieces of materials that were similar yet varied in forms, colour and texture in ways that initiate a chain of aesthetic experience in viewers.

3.Ngozi-Omeje Ezema gave this explanation regarding her use of the leaf motif during my visit to her studio on January 3, 2021.

4.In his essay, “From Masks to Metal Cloth: Artists of the Nsukka School and the Problems of Ethnicity,” Sylvester Okwuonudu Ogbechie uses the term ‘language of sublime awe’ and ‘radical aesthetics’ as stylistic markers of Nsukka school art. The aesthetic regime of this style reflects dialogic encounters between indigenous knowledge and local/global sites of artistic production.

Fabulous! The work is so engaging. Thank you for it.

Stunning body of work, thanks for the article about Ngozi-Omeje Ezema.