LAMBERTVILLE, NJ—This is Part Two and deals with Contemporary ceramics (as opposed to Modern) on Rago Auction Modern Design (12 September, 2020) sale. The pieces were mostly good quality, some were exceptional. This seemed to be a perfect canary in the mine, testing whether this market IS moving up, hovering or going down. The canary just survived. Most prices held although there were some shockers, mainly Voulkos.

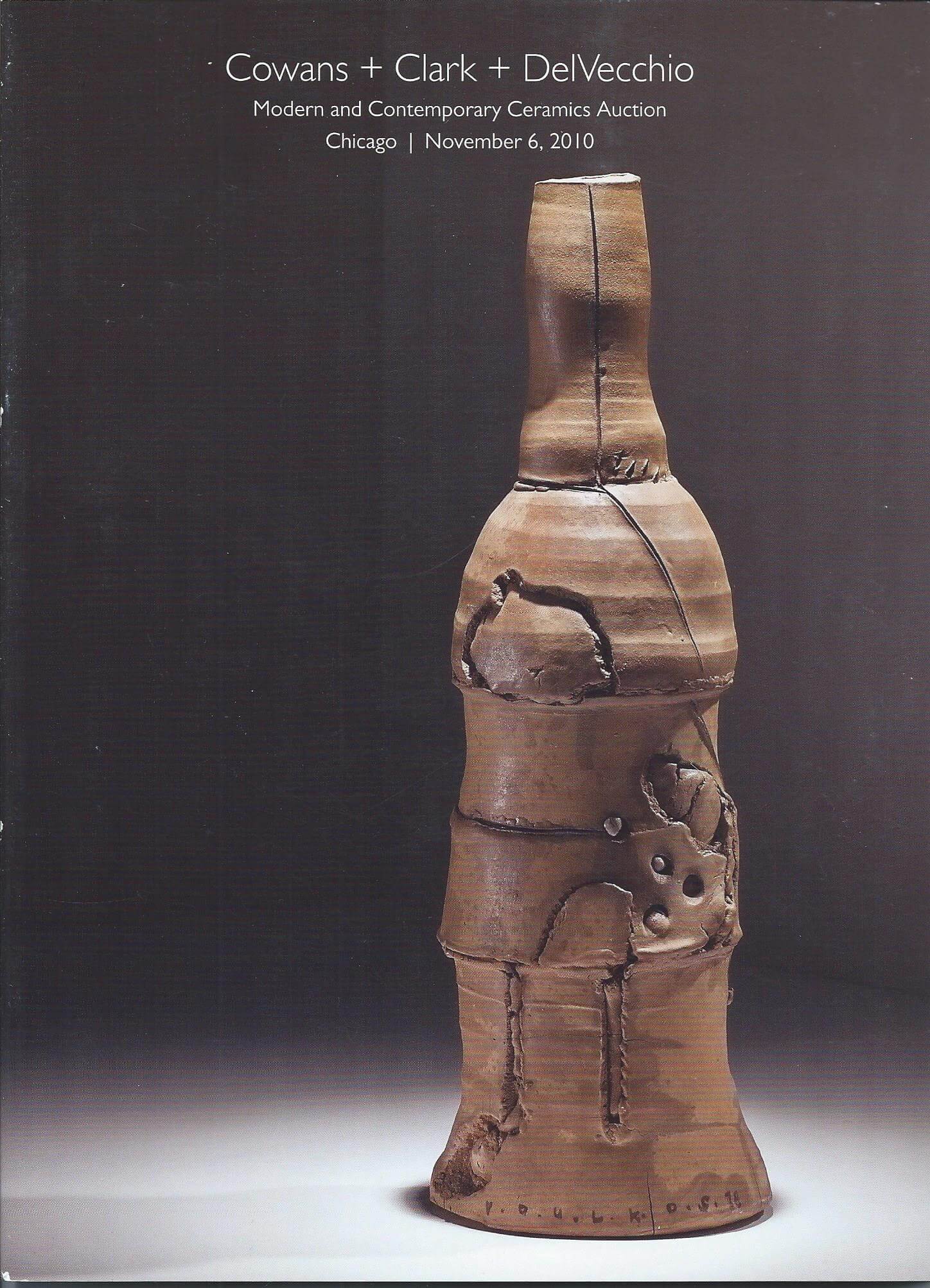

Our auction experience has taught us to read the stories that underlie results. Our gallery in New York closed in 2008. In 2010 Mark Del Vecchio and I created a ceramics auction, Cowans + Clark + Del Vecchio, with the legendary auctioneer, Wes Cowan (a PBS star on Antiques Roadshow and History Detective).

On our maiden voyage in Chicago with SOFA (hugely controversial) on 7 November 2010 we set a record for a vessel by Voulkos that still holds, the masterful Gash (1978). Since the prices have slowly inched downwards. Out of the blue, on the Design Evening auction at Phillips in New York (12 December, 2017) Voulkos’ Rondena (1958) set a staggering new record for his sculpture, $915,000. The estimate was $300,000 to $500,000.

Has Voulkos finally achieved market zeitgeist?

Immediately afterwards? Prices dipped, a lot.

Given that, how did two impressive Voulkos Stacks do last week at Rago? Did his value turn a corner?

Yes, but the wrong corner.

Peter Voulkos

Untitled Stack

1968

Estimate: $20,000-$30,000

Result: $31,200

One Stack was dated 1968 and the other 1973. Both were stunners but not aesthetic equals. Voulkos had departed ceramics in 1965, trading the kiln for a foundry furnace and bronze sculpture. This sculpture grab failed. Only a few ceramics were made during his decade long bronze age. In 1968 he had a brief return to clay.

1968 is a plus. Voulkos’ groundbreaking period was between 1955 and 1968 and they bring in excellent prices. This Untitled Stack is undeniably handsome, nearly three feet tall, with a length-wise smear of blue glaze. The classical architecture flows effortlessly from top to bottom. It has a drawback. While beautiful, it is tame compared to other action-pots of that decade.

Peter Voulkos

Untitled Stack

1973

Estimate: $20,000-$30,000

Result: $27,500

The black Untitled Stack, from 1973 is an exceptional vessel, one of the finest I have seen, a catalog of what was to come; svelte, black glaze, a languid and erotic form, explosions of energy and surface interventions; holes, push-throughs, pull-throughs, shallow cuts, violent deep slashes, gouges and ragged edges.

How did the auction buyers react to these two stacks?

The 1968 Stack with an estimate of $20,000-$30,000 sold for, $31,200. The black stack with an estimate of $20,00-$30,000 sold for S27,500, a real shocker.

This decline questions Voulkos’ legacy. We would speak of him as one of the top ten ceramic artists of the 20th century. He was our God. His arrival in the highest canon was considered just a matter of time.

But as time progressed, it became clear that he was not in the top ten but still of significance. His students sped past him for promotion to the art canon, Ken Price and Ron Nagle with Matthew Marks and John Mason with Gagosian.

Why is this? His ceramic career has four phases; functional pots, revolutionary pots and wood-fire pots with a beautiful short flutter of gas fired plates and stacks 1978-1979. Market consensus is that he had one great period, the revolutionary pot and never achieved this importance again. His last period of wood-fire pots were drubbed critically as being “embarrassingly masculinist” by one critic and “unable to escape 1950” by another.

Then too he was self-destructive and did many things that impacted negatively on his career, perversely tying himself to the craft world. His two big exhibitions while living, his retrospective and survey of wood-fire vessels were both held at the American Craft Museum, a kiss of death in New York. He did not have a solo show in any New York art museum or major gallery. Sorry, Charles Cowles was not major. One exception was having his paintings hung in the Member’s Lounge at MoMA. Also, there is little major writing about Voulkos, even today.

More importantly, his audience today is small, particularly in the higher price range. And when it comes to product (I like the no-nonsense retail bluntness of that term) the pool is shallow. He was always praised for his huge output, true of the functional period but not thereafter. It is estimated that 85% of his best works from the revolutionary period are in permanent collections. Collectors want to play, buy and build. When there is nothing to acquire, they move on. See a comment about this in Part 3 Ohr.

Peter Voulkos

Untitled Plate

1987

Estimate: $4,000-$6,000

Result: $8,750

His plates are the exception to all rules. From Montana in 1947 to his death in 2002 at Bowling Green University, the plates have been on the mark, perfectly capturing the energy and syntax of every shift in the rest of oeuvre, never wavering. Well, maybe, occasionally.

Peter Voulkos

Untitled Plate

1990

Estimate: $5,000-$7,000

Result: $11,875

The market has been blind to this. Even in the posthumous survey of his revolutionary years at the Museum of Arts and Design (in the craft arena again) there were only two plates in the entire exhibition!

Peter Voulkos

Untitled Plate

1973

Estimate: $4,000-$6,000

Result: $7,500

The prices plates received on this auction—$7500 to $11,875—were the prices Mark and I sold similar work for through the 1990’s and 2008. Sooner or later their importance will be validated. So, if you want to buy, go for sooner.

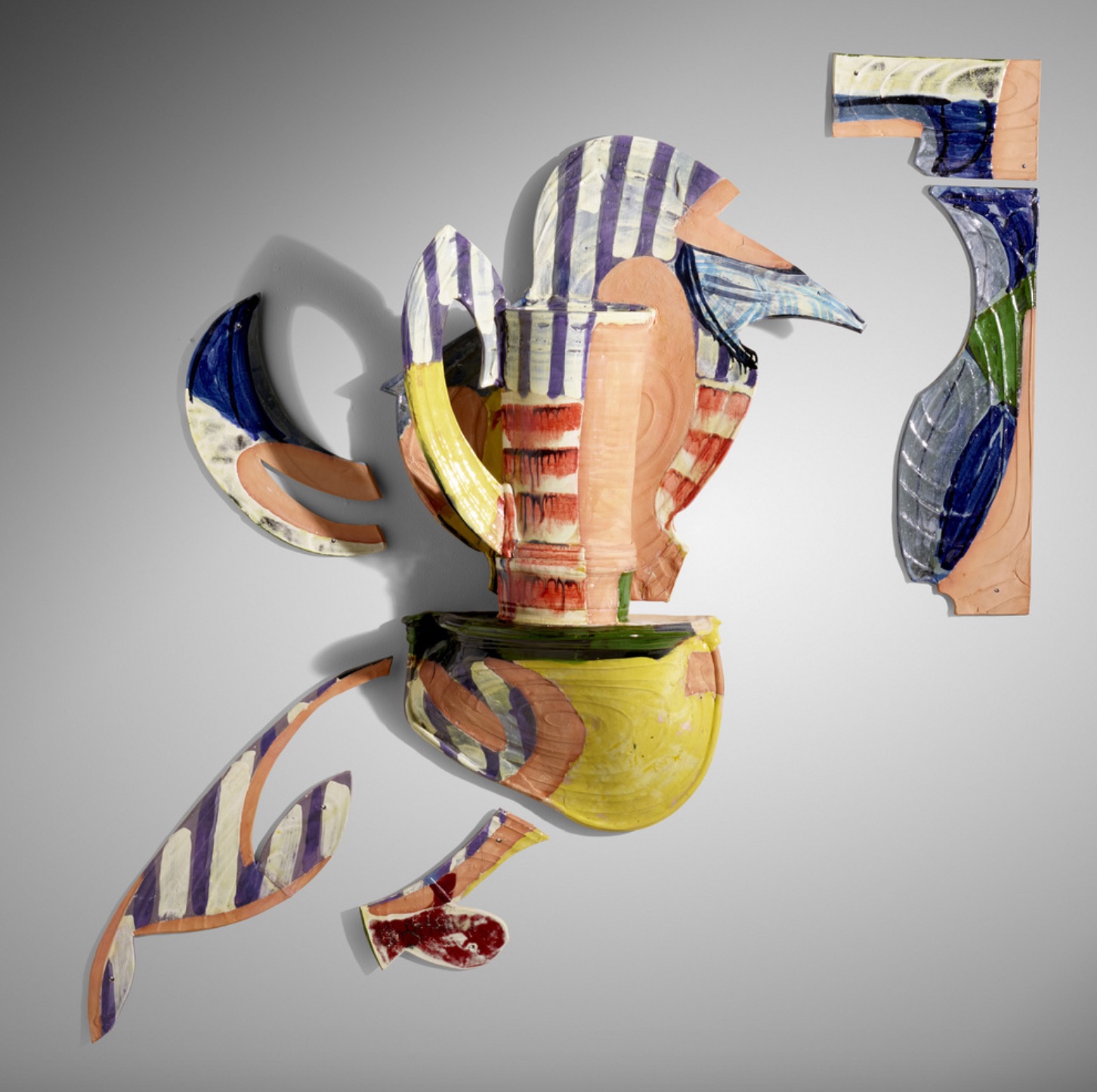

Betty Woodman

Balustrade Relief Vase #13

1995

Estimate: $10,000-$15,000

Result: $47,500

Robert Turner

Ashanti

c. 1975

Estimate: $3,000-$4,000

Result: $3.500

Michael Lucero

Lady with Ohr Hairdo from the Pre-Columbus series

1991

Estimate: $2,000-$3,000

Result: $2,340

For the rest, the prices were more or less where they have been for much of this decade. Betty Woodman did well at $47,500, and the great Bob Turner still bobbed around $3,500 to $4,500. What was painful was seeing Michael Lucero’s work go into free fall. It deserved much more than $2,000 to 3,250, particularly his delightful Inca figures that once sold for over $20,000.

The final judgment? Undervalued and hovering.

Garth Clark

Bodil Manz

geometric vessel

c. 2000

Estimate: $2,000-$3,000

Result: $2,000

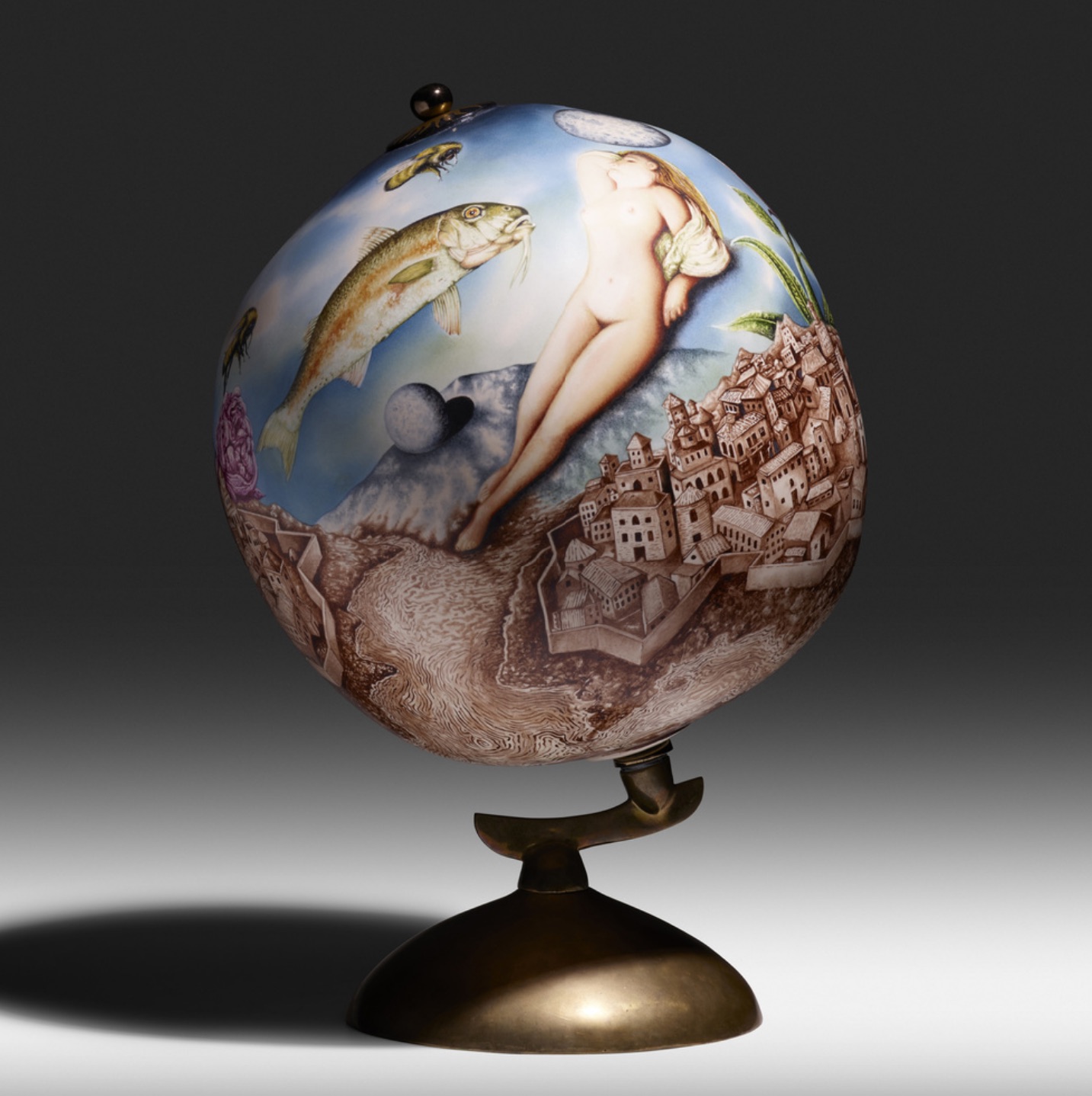

Kurt Weiser

Luna

2009

Estimate: $4,000-$6,000

Result: $7.500

Add your valued opinion to this post.