Cfile is based in Santa Fe, NM, a culturally active town of 80,000 people, 14 museums and a international Opera season. In the past month is had show, three major exhibitions that could have graced a New York Gallery: Denmark’s Bodil Manz’s largest US show with her daughter, a leading designer, Cecilie; Ken Price with Georgia O’Keeffe, and a large exhibition by Jun Kaneko. Add to that an exhibition touring the US (now at the Gardiner Museum, Toronto after New York) by Santa Fe artist, Cannupa Hanska Luger, and stunning new work by Kukuli Velarde.

TORONTO––I have followed Cannupa Hanska Luger work closely (we are both Santa Fe residents) ever since his ceramic boom boxes of 2013. While he works multimedia, clay and fire is a constant. With each passing year his work has picked up more strength. In the last few years his mature voice has arrived, recently working mainly with installations.

Image courtesy of UCCS Galleries of Contemporary Art

His 2016 work, The Mirror Shield Project, Luger deals with confrontation between big oil and Indigenous people over the Keystone XL pipeline in North Dakota. The Mirror Shield Project was initiated for and at the Oceti Sakowin protest camp near Standing Rock, ND in 2016. On Luger’s website its intent is explained:

“This project was inspired by images of women holding mirrors up to riot police in the Ukraine, so that the police could see themselves. The materials I chose to use were affordable and accessible, and I chose to use a reflective mylar on a ply-board instead of glass mirror for safety and durability.

It speaks about when a line has been drawn and a frontline is created; that it can be difficult to see the humanity that exists behind the uniform holding that line. But those police are human beings, and they need water just as we all do, the mirror shield [one sheet of plywood and cut it into 6 shields with reflective mylar instead of glass mirrors, a safety factor] is a point of human engagement and a remembering that we are all in this together.”

Luger then created a tutorial video for social media inviting water protectors to create their own mirrored shields. Luger was humbled “people from across the Nation created and sent these shields to camps in Standing Rock. The Mirror Shield project has since been formatted and used in various resistance movements across the Nation”.

Luger’s fight is also personal, as he was born in Standing Rock:

“My dad’s side of the family, have a ranch on the Standing Rock reservation. My mom’s side is from Fort Berthold reservation, which is where the current oil fields are. I watched that community get destroyed by the extraction of oil. I’ve seen wells poisoned. I’ve seen the cycles of boom and bust”.

To get a sense of his impressive intellect, eloquence, irony, knowledge if his culture, and ethical compass, I suggest listening to our Casita Confessions podcast featuring Luger.

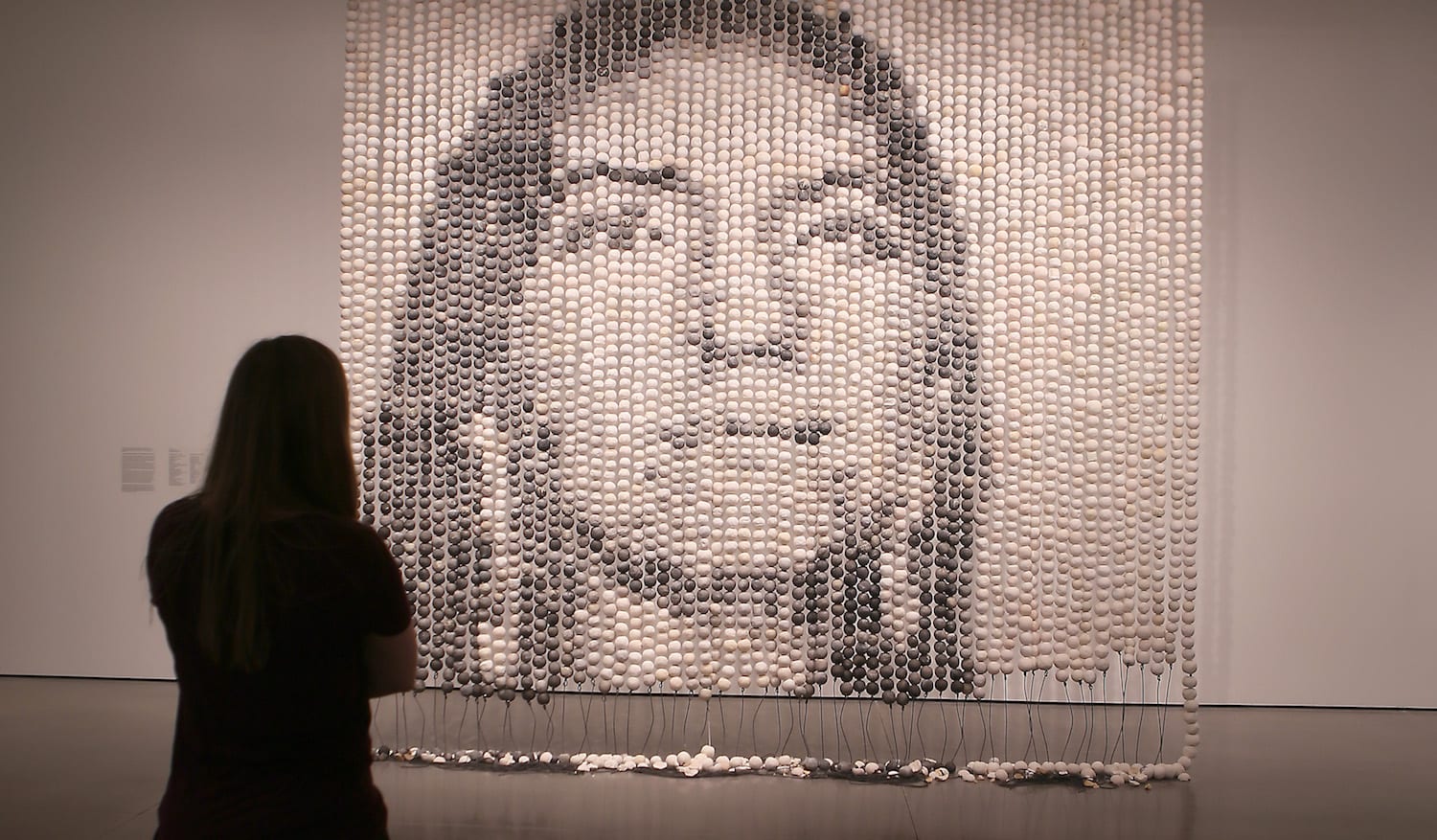

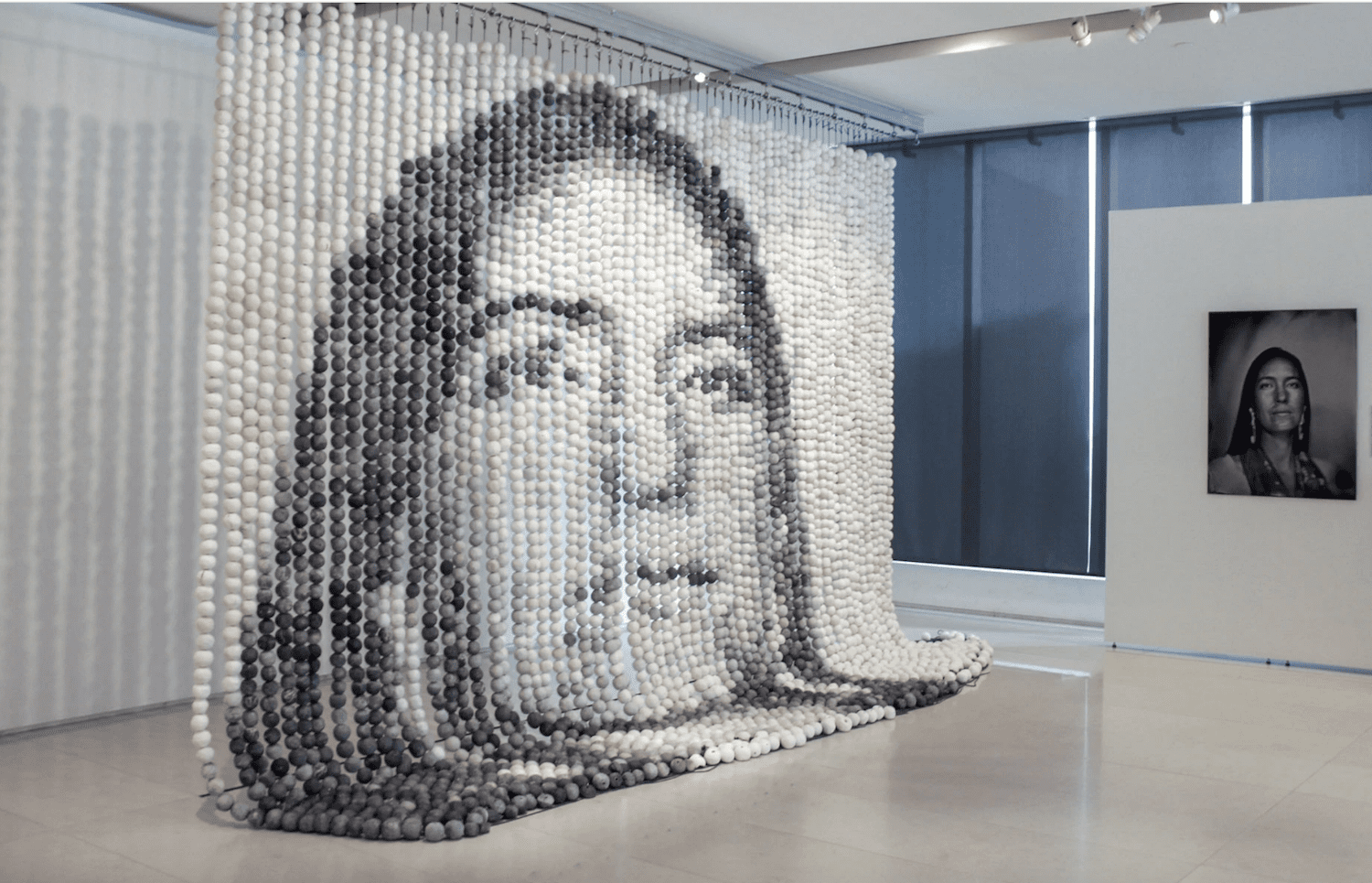

His current exhibition, Cannupa Hanska Luger: Every One & Kali Spitzer: Sister (Aug 30, 2019 – Jan 12, 2020) arrives at the Gardiner Museum from New York at the at the end of a four-museum tour. “Every One visualizes the data behind the MMIWQT Project,” writes curator Sequoia Miller. It is the entry portal to a shocking situation, yet at beckoning seemingly harmless curtain made of large ceramic beads the size of baseball, a nod to this Native craft. Below is a description of the project:

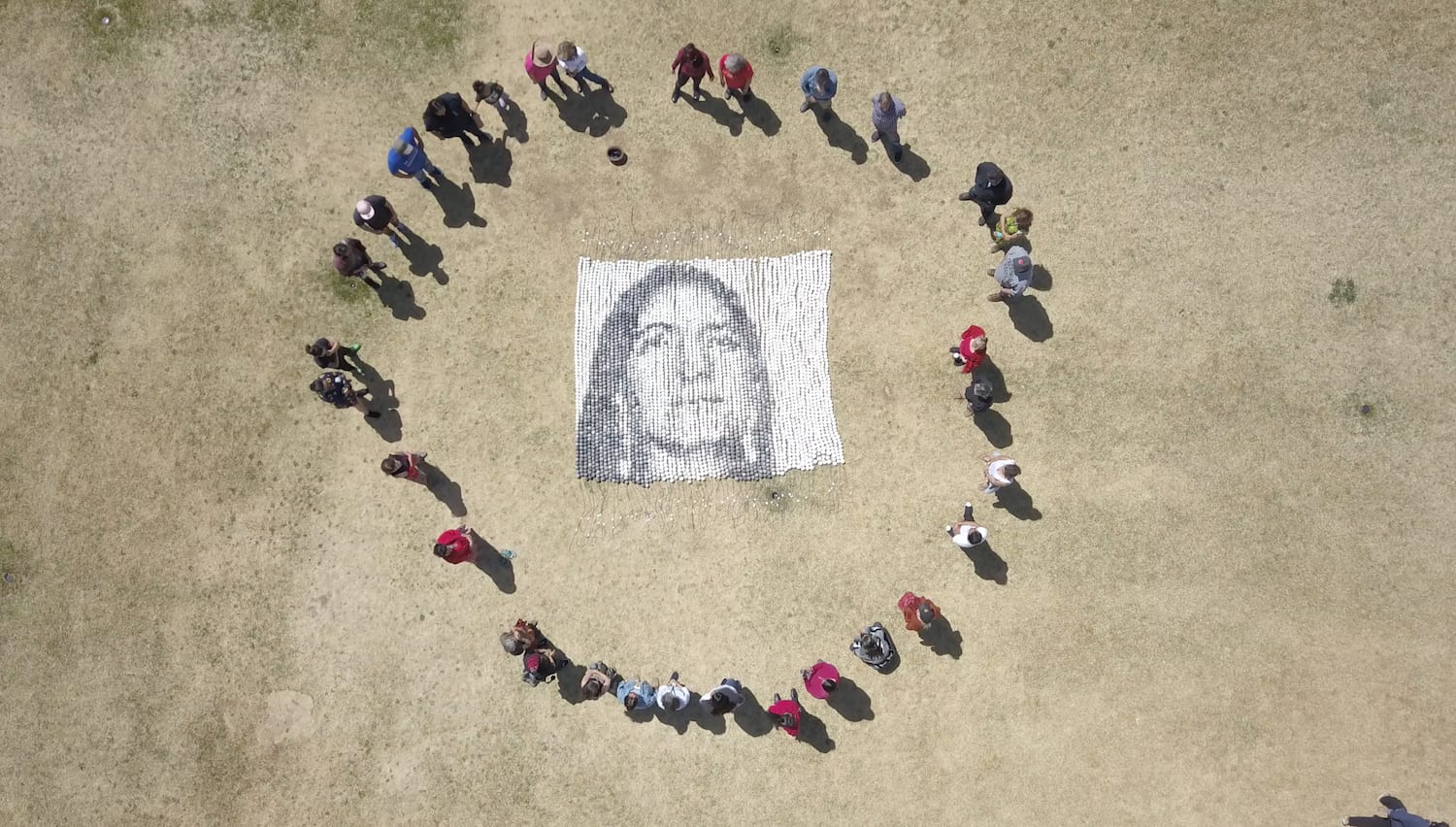

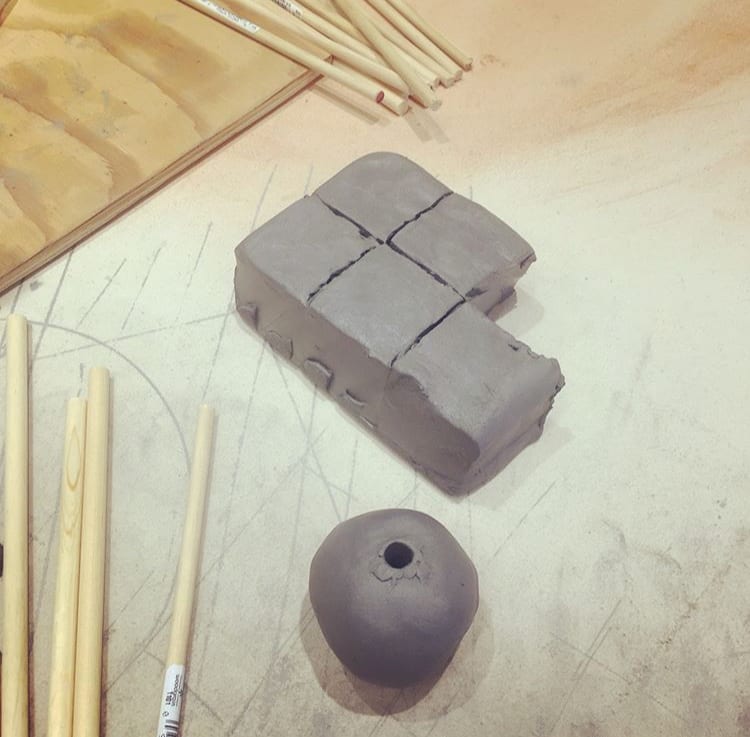

“Responding to data collected by the Native Women’s Association of Canada, Luger created a call to action via a video shared through social media that invited communities across the United States and Canada to make 2-inch clay beads, each one representing a unique person who has been lost. Hundreds of participants held workshops, both with Luger and on their own, making the beads in studios, community centers, universities, and private homes. These experiences generated over 4,000 beads, as well as numerous conversations, stories, and occasions for healing through clay”.

www.cannupahanska.com

Image courtesy of UCCS Galleries of Contemporary Art

Miller praises Luger publicly for exposing the “crisis of missing native women, transforming large and abstract numbers into a representation of individual lived experiences”.

Every One stands in solidarity with the photograph Sister by First Nations artist Kali Spitzer. The image depicts an anonymous Indigenous woman who has lost her sister due to the crisis the work represents.

In her own work, Spitzer explores the individual stories behind the MMIWQT crisis through portraiture and self-representation. She works in the medium of tintypes, a photographic process popular in the 1860s and 1870s, particularly with settlers in the Canadian and American West. Spitzer claims this process, “adapting it to create images of contemporary Indigenous survival.”

Those “transforming large and abstract numbers” are shocking and exposed by the New York Times, as writer John Hanc reveals what is a killing field:

“In June, the Canadian government released a report after a nearly three-year inquiry found that 1,181 indigenous women were killed or had disappeared across the country from 1980 to 2012. Estimates by indigenous women’s groups have put the number much higher.

The problem is not unique to Canada: Although the issue has attracted less attention in the United States, the National Crime Information Center reported that in 2016, there were 5,712 reports of missing American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls. Only 116 of those were logged in the United States Department of Justice’s missing persons database, the report said”.

One can assume that most of these women have been murdered. Few, with their close ties to family and place, would just disappear. The assumption of foul play is further likely given that homicide is the third leading cause of death for indigenous women ages 10 to 24. In Canada in 2015, a quarter of all women murdered were indigenous—a sharp increase from 9% in 1980. And that’s not even counting the women rated as “missing.”

Details about rape are also disturbing. Native women are 2.5 times more likely to be raped. The statistics are bad enough, but for cultural reasons, they’re often underreported, so that number is much higher. Pueblo and reservation police take some of the blame for the inaction. They serve small, tight communities and given the shame that might arise, often sweep sexual assaults under the rug.

The bigger problem is that 86% of the rapists are non-Native, mostly white. According to Cheryl Bennett, an Arizona State University professor who studies hate crimes targeting indigenous peoples, “if a white person commits murder or rape against a Native American person, the federal government would have jurisdiction over those crimes, instead of the tribe or state government.”

Disinterest from the judicial system and an impenetrable maze of federal, state, and tribal jurisdictions, allows perpetrators to act with impunity and evade justice. Even when tribal law enforcement sent sexual abuse cases to the FBI, prosecutors declined more than two-thirds of them, according to a 2010 Government Accountability Office report. Investigations are few and convictions are even fewer.

Federal law prevents most courts from sentencing non-Native perpetrators to more than a year in prison, released in a few months for good behavior. Most murderers and rapists will escape punishment and are well aware of this fact, hunting with impunity. In a sense nothing has changed from the 19th century.

But is what Luger does art or propaganda? The latter is what most “issue-art” ends up being. Propaganda, no matter how much we agree with issues, is the enemy of art. It is preachy, didactic, and imprisoned by good intentions.

Every One uses sly art to part the curtain. There is no obvious anger to alienate the viewer though I am sure there is a deep well of that within this artist and have seen flashes of it. How could there not be? Instead the work beckons because alluring, charming, and welcoming. But in fact, it is an ambush, as one finds oneself trapped in the violence of its content.

Red Shawl Society Solidarity Action at Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe, NM 2018, Photography:: LeRoy Grafe

Luger is being accepted as an important young contemporary artist, winning the first Burke Award. Furthermore, a small sector of the fine arts is finally acknowledging Native art. Sure, some do this only to burnish liberal credentials, but increasingly some are becoming woke to the power of these artists.

His friend Galanin, who, unlike Luger, puts his rage front and center, was one of the first four artists to remove their work from the Whitney Biannual to protest a trustee, the King of Tear Gas, since removed. This prominence is new.

Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe, NM 2018, Image credit: Cannupa Hanska Luger

There can be a wave of artists emerging today who exist but have not been considered. Thereafter it will be a slow process. Producing major artists is difficult process in Indigenous communities for a multitude of reasons. To begin with they are only 2% of the American population with neither wealth or political clout. Also, they see the United States as a bogus country.

Resources we take for granted, hundreds and hundreds of art funding organizations (privileging a mainly white art world) are rare in the reservations and Pueblos. A welcome move is that more and more Native artists are going to art schools. As more make it to the mainstream, their hands can reach down and pull up other artist and that success will be political, not commercial.

My gaze is that of white man (for which I make no apology) and I am careful to keep this in mind when I write about Native art. I can only see from the outside, which is all that I deliver. Indigenous artists, unfunded, neglected and invisible, feel it from inside and I make no pretense to “feel their pain”. The best I can do, as a writer, is to shine a light on the inequities and talent awaiting support.

Back to Luger. He has created artwork that is elegiac. In amongst this word’s various definitions is “a song or poem of sadness”. There is no better description for Every One. May it become a loud, persistent chant.

Luger is currently in Los Angeles working as co-director of a new opera titled Sweet Land.

–Garth Clark, Cfile.org Editor-in-Chief

Editor’s Note: Please note that I have worked on this piece for some time. I have lost track of some sources of content; no doubt confused some as my own words. My apologies and correct any errors in the comment section below.

About the Artists:

Cannupa Hanska Luger is a New Mexico-based, multi-disciplinary artist. Raised on the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota, he is of Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Lakota, Austrian, and Norwegian descent. Using social collaboration and in response to timely and site-specific issues, Hanska Luger produces multi-pronged projects that take many forms. Through monumental installations that incorporate ceramics, video, sound, fiber, steel, and cut-paper, Hanska Luger interweaves performance and political action to communicate stories about 21st century Indigeneity. This work provokes diverse publics to engage with Indigenous peoples and values apart from the lens of colonial social structuring and oftentimes presents a call to action to protect land from capitalist exploits.

Kali Spitzer is Kaska Dena from Daylu (Lower Post, British Columbia) on her father’s side and Jewish from Transylvania, Romania on her mother’s side. She is from Yukon and grew up on the West Coast of British Columbia in Canada on unceded Coast Salish Territory. She is a trans disciplinary artist who mainly works with film – 35mm, 120, and wet plate collodion process using an 8×10 camera. Her work includes portraits, figure studies, and photographs of her people, ceremonies, and culture. Her work has been exhibited and recognized internationally. Spitzer recently received a Reveal Indigenous Art Award from the Hnatyshyn Foundation in Canada and was featured in the National Geographic and Photo Life magazine in 2018. At the age of 20, Spitzer moved back north to spend time with her Elders, and to learn how to hunt, fish, trap, tan moose and caribou hides, and bead. Spitzer documents these practices with a sense of urgency, highlighting their vital cultural significance. She focuses upon cultural revitalization through her art whether in the medium of photography, ceramics, tanning hides or hunting. She views all of these practices as art and as part of an exploration of self. indigenous peoples. But when tribal law enforcement sent sexual-abuse cases to the FBI and U.S. Attorney Offices, federal prosecutors declined more than two-thirds of them, according to a 2010 Government Accountability Office report. When I see exhibitions with activist intent my litmus test is simple. Does it work first as art? If not, no matter its good intentions, no matter how much I support the intent, it becomes propaganda, too didactic, too limited. I can appreciate both, but I am looking for art.

I find Luger’s work inspired and empowering. I had not known of it before. A beautifully written introduction, Garth.