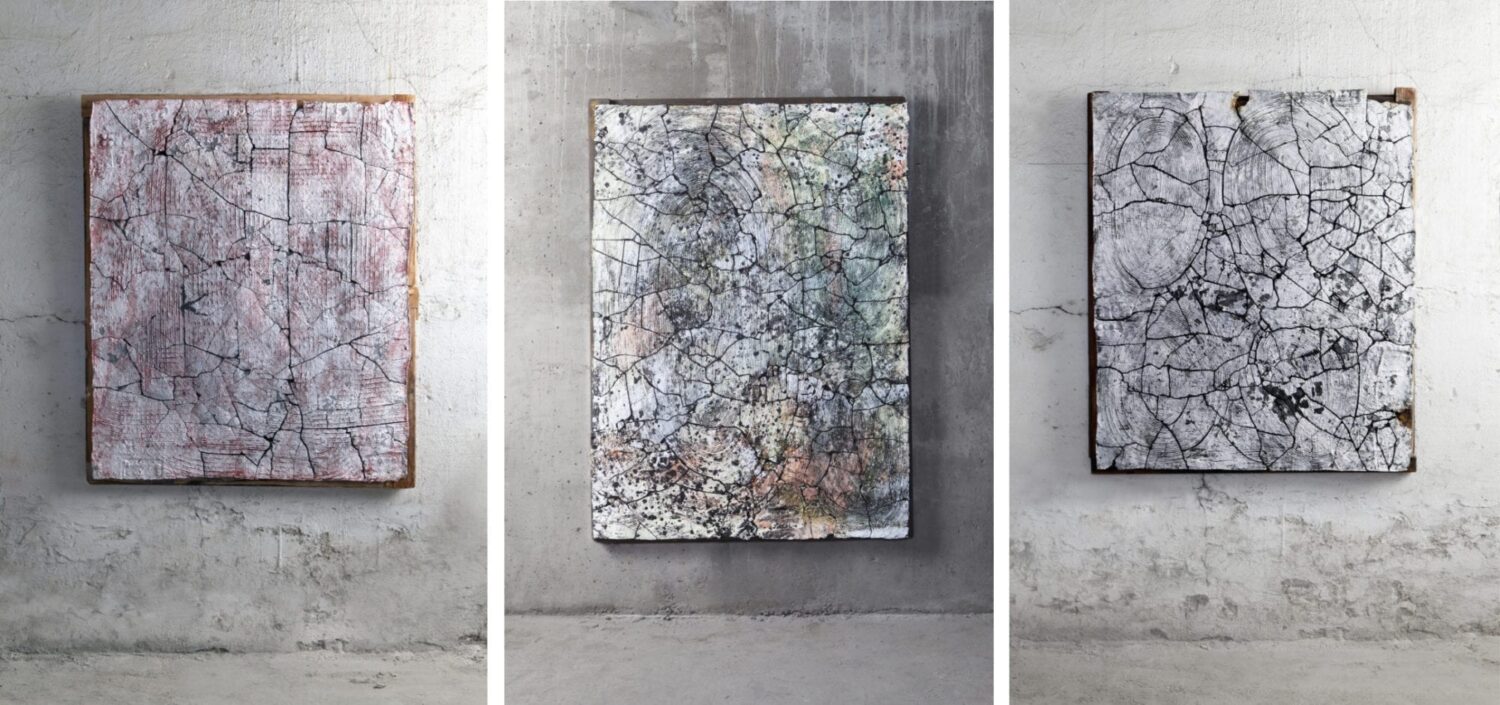

NEW YORK––Internationally recognized Finnish artist Pekka Paikkari fractured works at Hostler Burrows (May 3 – June 14, 2019) comprise the artist’s first solo exhibition in the United States. Distinctive, singular, the works are the result of his thorough investigations into the technical properties of clay, which he then manipulates in interesting ways, writes the gallery.

He has, for instance, developed a unique technique for drying clay. Although the web-like, fractured surface of dried clay is the outcome of a natural process, the artist controls it in order to obtain the desired pattern. Only then are the clay elements fired in the kiln. The process could be described as a controlled accident. Paikkari places particular emphasis on leaving the marks of hands and tools on his clay, bringing the act of creation closer to the observer.

Hostler | Burrows

The following essay Ice Breaking/Jäät lähtevät is by Ezra Shales, PhD, Professor, History of Art Department, Massachusetts College of Art and Design.

Chalk crawls on a blackboard; an ice cube crackles in whiskey; a log snaps in a fire. Some of these sounds are jarring and others prick our ears sharply even though they soothe. The invisible can make us blink and a quiet rumble pull our entire bodies like an oceanic undertow. We can hear Pekka Paikkari’s works of art as well as see them, and the scratched forms echo tactile memories of movement, landscape and mud, however hard and still they are. Composer Timo Laiho lyrically described that he experienced Paikkari’s 1992 work of stacked ceramic tiles, titled Jäät lähtevät, synaesthetically, perceiving the sculptural tension as an aural sensation, too, and his insight is worth noting before one begins to describe the fractures in Paikkari’s sculpture. For ‘cracks’ are not merely superficial occurrences but the records of Paikkari’s labor, the traces of pacing and full body contact, of alchemical knowledge, and of decades of accumulated knowledge as a fire tender. On a very direct level, any ten-year old child understands Paikkari’s sculpture when they anticipate the sound and reverberation of smashing a stone to test a sheet of ice, and watching the water gurgling through channels. Wonder grows in such furrows. Peer what lies beyond, the cracks whisper.

A virtuoso on the potter’s wheel, Paikkari’s fractures are not to be weighed lightly or considered apart from skill or without human labor. He is an artist-in-residence at Arabia, the storied century-old Helsinki ceramic factory that was the pride of Finland from its realization of independence and an essential part of the country’s cultural recognition by Europe and the United States in the 1950s. He began working in the model making department in the 1980s, and still has the skill to beat on his wheel to outperform any rapid-prototyping printer. To reclaim

Paikkari’s fractures are only possible and achieved with manual (and foot) application, skilled manipulation of the chemistry of both clay and the chemical composition of metals and oxides such as aluminum and lithium, and control of fire and its effects at temperatures of 1400 Celsius in conditions with and without oxygen. His education was in Finland but worldly, with exposure to Jun Kaneko and Peter Voulkos, among visiting Americans. And he has steadily exhibited work since 1985, and internationally alongside Annabeth Rosen, Torbjørn Kvasbø, and Anders Ruhwald.

Paikkari evokes both Promethean placemaking in archaic art and also the boldly Modernist ruptured canvases of Lucio Fontana. He delves into entropy and how things fall apart. His expansive fields of shards seem to rotate spatially and demarcate gestures of inscription. The concentric marks are a sort of gestural hieroglyphic asserting nothing more than place and human presence. And my respect only increases when I realize that he has willingly given up the calm of classicism and the symmetry inherent in the wheel for his own peculiar sense of monumentality that includes archeological stress and the forces of disintegration.

If some artists emphasize clay’s plasticity and others summon its geological density, few have captured the process of desiccation as poignantly. His wall pieces bring us into direct contact with vast stubble fields of wintry ice cracking. He turns parts of bicycle, toys and tools into withered ritual objects. His fragments articulate our collective failure to build enduring tools, or the susceptibility of human artifice to drying out, our bodies ossifying into skeletal artifacts. These are not trompe l’oeil artifacts but memories and reveries forced into three dimensions, and things squeezed so as to confirm their existence. It is wondrous that they are clay but to only see material and not mindful reflection on mortality misses the point.

Three-meter high bottles are large enough to hold all our hopes and disappointed dreams of genies and yet portable enough to bring home as shrines to the memory of water and times when classicism seemed a romantic possibility. If in his magisterial Shape of Time George Kubler sorts art by seeing all paintings ‘planes,’ vases and baskets as ‘envelopes’ and such things as stone carvings as ‘solids,’ Paikkari’s shard somehow moves amongst all three of these. The fragment is only a small bit of flatness yet beckons our imagination to delineate larger outlines and forms. Surface impressions might suggest a rhythm or pattern of building, and it is true, many ancient fragments tease archeologists to believe that basketmaking was a source of decoration in early pottery and perhaps even a translation of meaningful legible ornament. Yet the clay shard is dense, impenetrable, no matter how many speculative pasts and imaginary futures we hope we might conjure from it. In the desert, the shard evokes an invisible city, in the contemporary street it can be as life- affirming and expressive of community-building as an acorn underfoot in the forest.

Paikkari’s flasks might be mountainous impersonations of ancient Babylon, but if they bring us to value the inscrutable pot shard as evidence of the fragility of our world and all of our assumptions about the existence of civilization, they will have had a very useful function.

––Ezra Shales

Paikkari writes in his artist reflections that the human presence and is the starting point of art.

Clay is a flexible material for expression and as such contains the history of time. As an artist I construct a neverending story. Despite the physical appearance of the art work, whether it is placed on the façade of a building or is an installation consisting of several pieces, the dialogue between the viewer and the work defines its final form.

Pekka Paikkari

About the artist: Paikkari’s work is in the collection of the British Museum and Victoria & Albert Museum in London, the Ceramics Museum of Barcelona and the Shigaraki Museum of Contemporary Ceramic Art in Japan, among others. In 1989 he was awarded the International Biennial of Ceramics in Faenza, Italy (Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Ravenna). Most recently Paikkari was invited to participate in the exhibition “Ceramics Now: The Faenza Prize is 80 Years Old”, a special 60th edition highlighting international masters and emerging artists working in ceramic at the Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche in Faenza.

Add your valued opinion to this post.