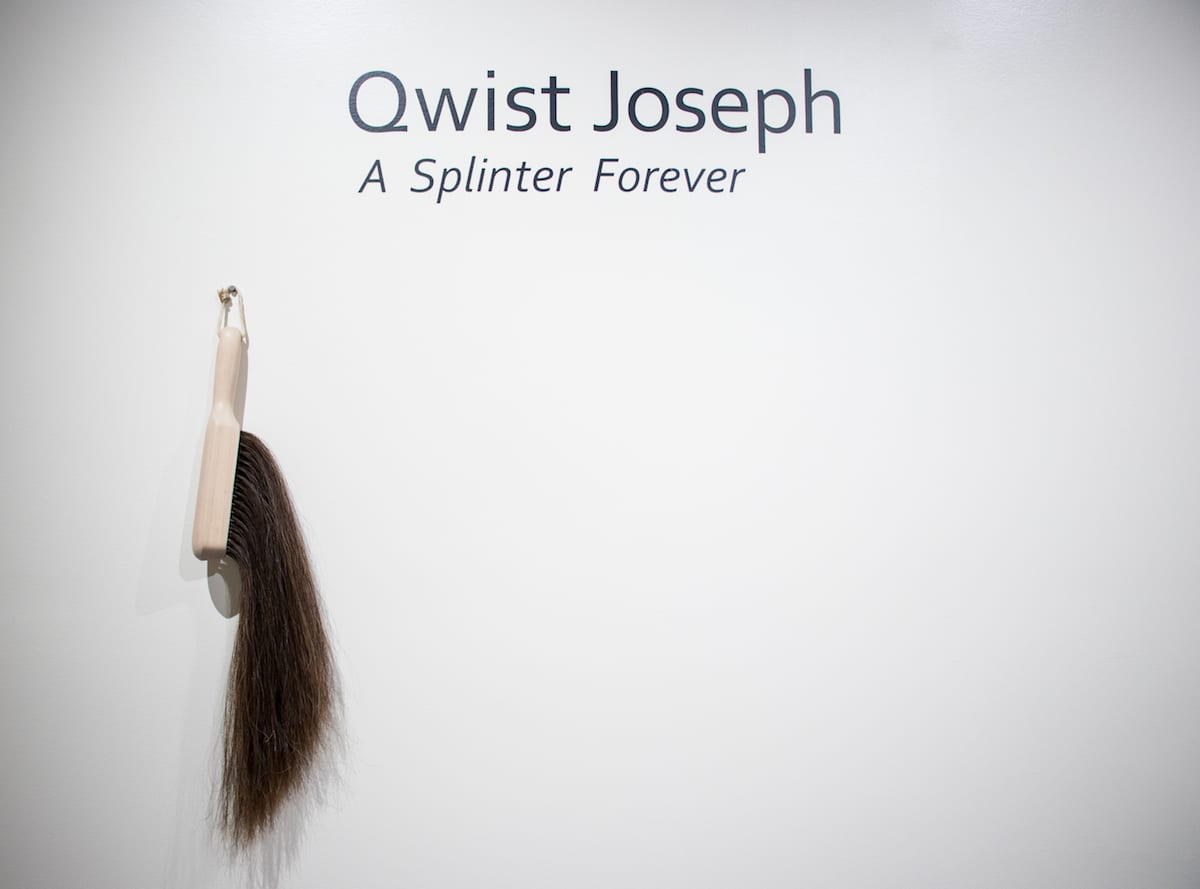

Qwist Joseph, a third generation sculptor, is currently a resident artist at the Roswell Artist-in-Residence Program. The artist’s RAiR exhibition A Splinter Forever was on view at the Roswell Museum and Art Center (January 26 – March 10, 2019). Joseph was selected as a 2019 NCECA Emerging Artist.

ROSWELL, New Mexico––Introspection and examination of self-image is nothing new to Qwist. He was diagnosed in his early twenties with the autoimmune disease, alopecia, and subsequently lost all the hair on his body. The experience was one that left him vulnerable to a new and uncomfortable appearance, and forced a re-evaluation of his identity.

“I had no choice but to surrender. I began to grapple with issues surrounding gender and toxic masculinity—topics I once was able to ignore through the privilege of living in a normative, able, white, male body.”

He reveals his studio practice gradually became more personal over time:

“I started to see, even without conscious effort, that the work was revealing things about my life, private things, things only I knew. I still try to allow my process to lead the way, but I am more keen to recognizing these signals and trying to capitalize on them.”

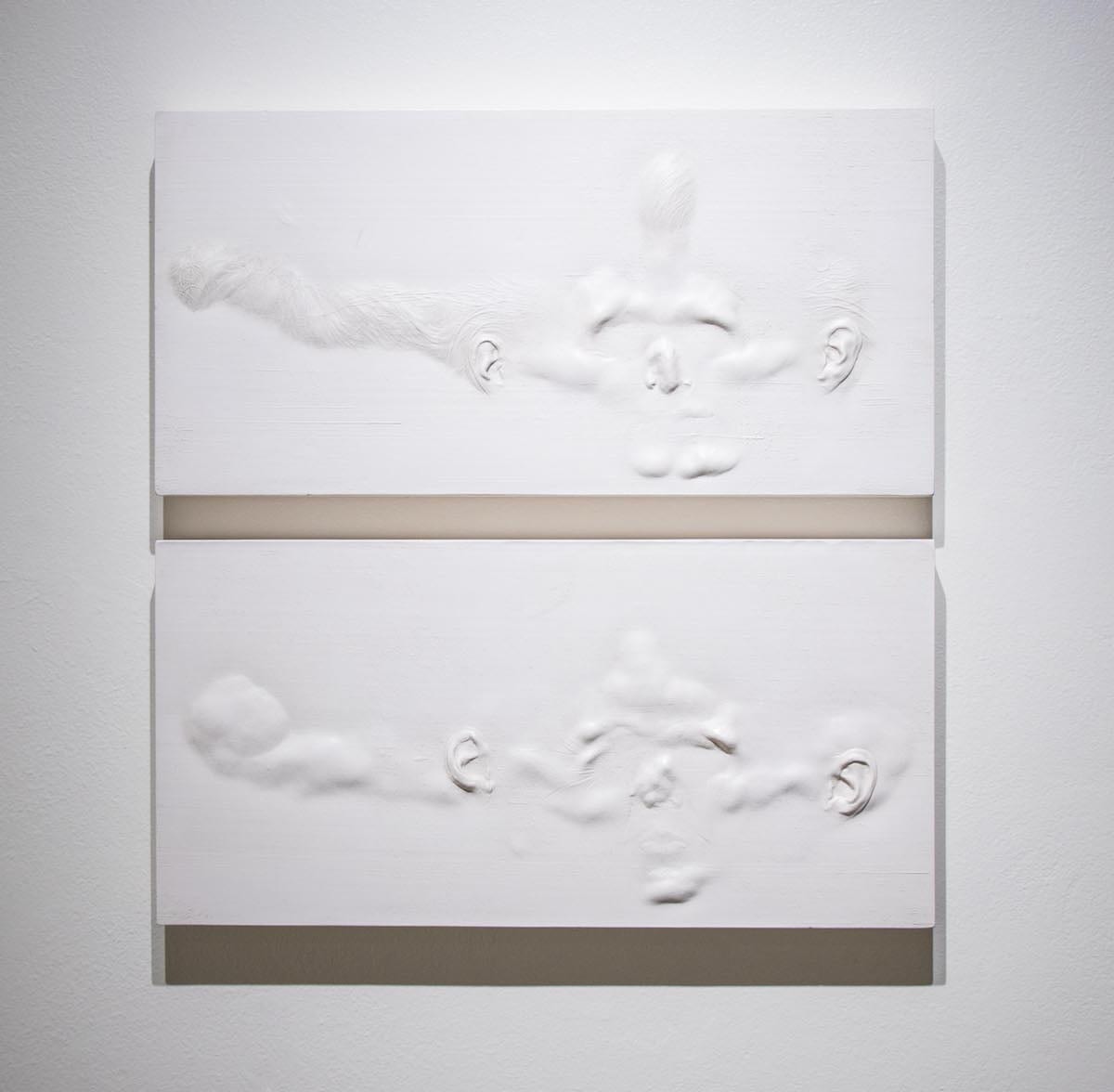

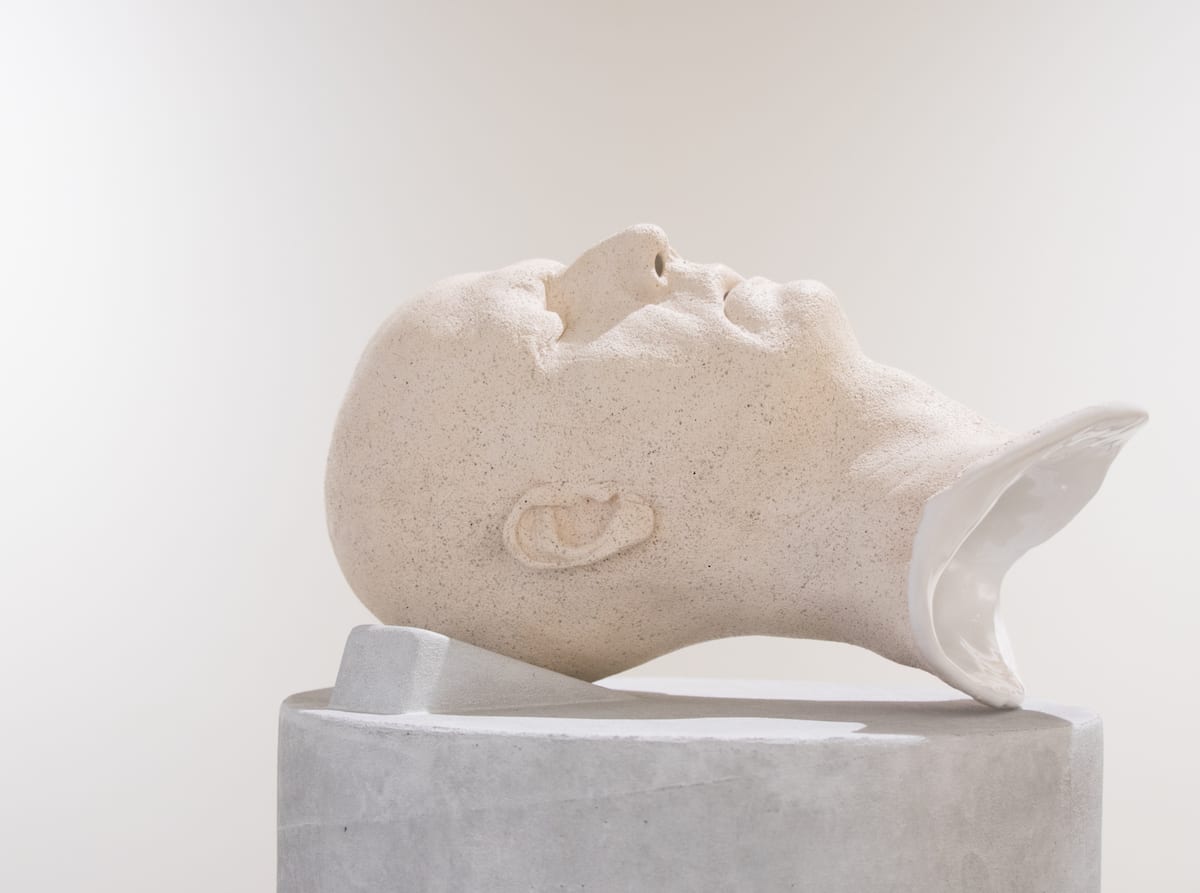

In A Splinter Forever, these topics are addressed with urgency as Qwist inches closer to his forthcoming marriage. This is encapsulated by All of You, All of Me, where the faces of Qwist and his fiancé are rendered on two tablets. The tablets are like inscriptions from ancient cylinder seals, made by pressing and rolling their faces across a bed of clay. The work is a physical record of their relationship.

In his exhibition statement, Qwist writes of nostalgia and preserving a memory:

“I find that sentimental longing has the unique power to distort our thoughts and even make us forget pieces of our past. To investigate this, I merge realism and abstraction and play with material expectations, emphasizing the fine line between genuine and fake. I’ve spent so much of my life presenting a false self, and I know I’m not alone.”

A curious object known as a strigil makes an appearance in the gallery. It is a hook shaped bronze tool, resembling a large shoe horn, that was used by athletes in ancient Rome and Greece to scrape the grime and sweat off their bodies. The strigil is presented on a wall opposite another piece that shares the title of the show: Spinario-A Splinter Forever. This piece consists of a large wrinkled sheet of synthetic rubbery material, vaguely resembling some type of ‘skin’, that is pinched under a gigantic sculpted splinter. These pieces, with the skin and the strigil, both speak to the idea of a protective barrier in one’s life, and the painstaking act of peeling it away in order to reveal an inner truth.

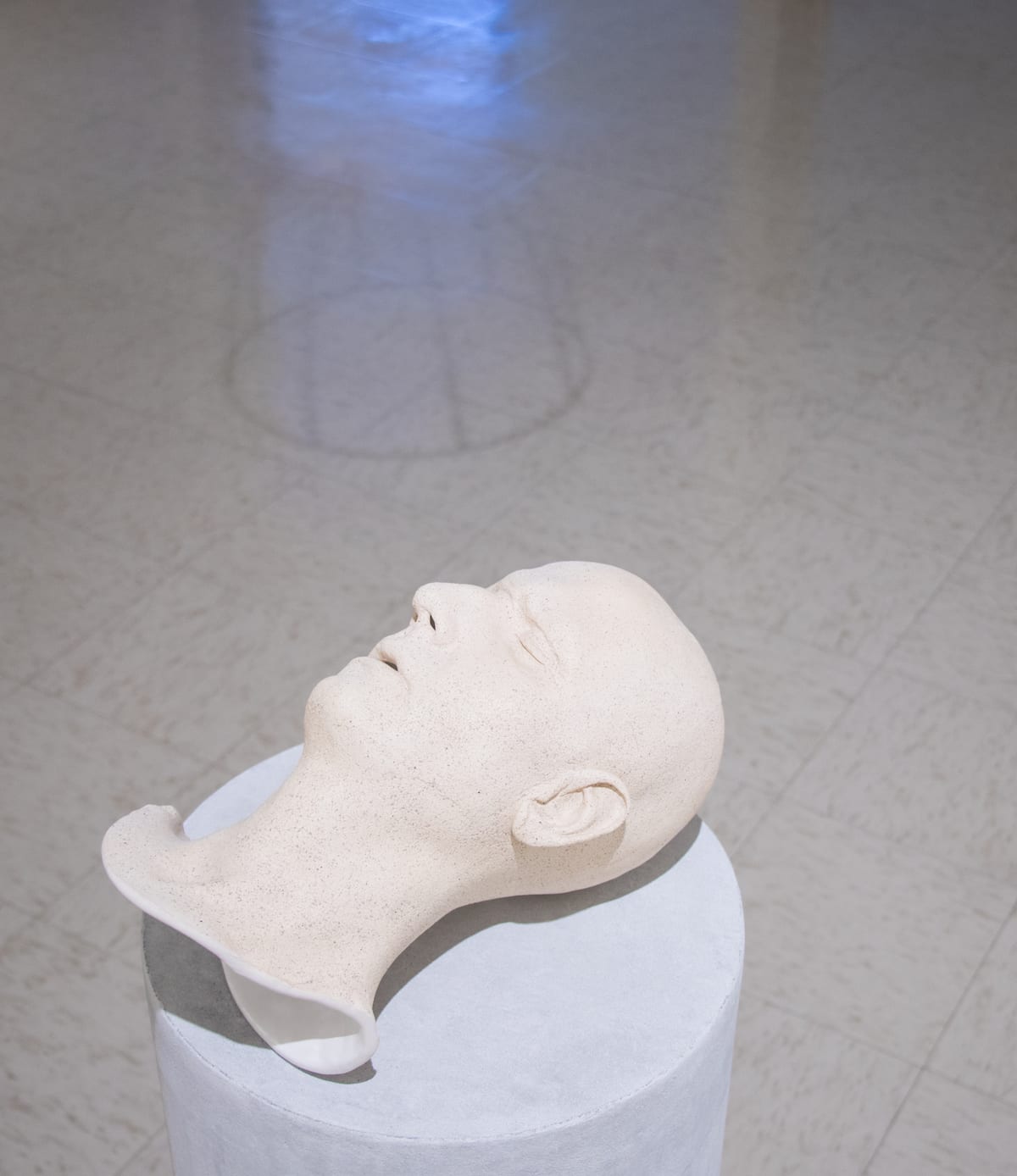

Spinario is the name most commonly given to a particular Hellenistic bronze sculpture of a boy tending to a wound on his foot. While the actual meaning of the sculpture is unknown, it is widely speculated that the young boy is a messenger who dutifully carried out his tasks until finally removing a painful splinter from his foot at the end of his work day. Qwist writes about how Spinario became the emblem of his exhibition, and serves as a symbol of self-improvement:

“There is a lot of mystery surrounding this sculpture and what we do know about it could very well be hearsay. I relate to this boy. He has gone to great lengths to help everyone around him, while neglecting himself. Even his history is up for debate and out of his control. I was inspired to pay homage to this boy in a way, and also use him as a device to dig into my own past.”

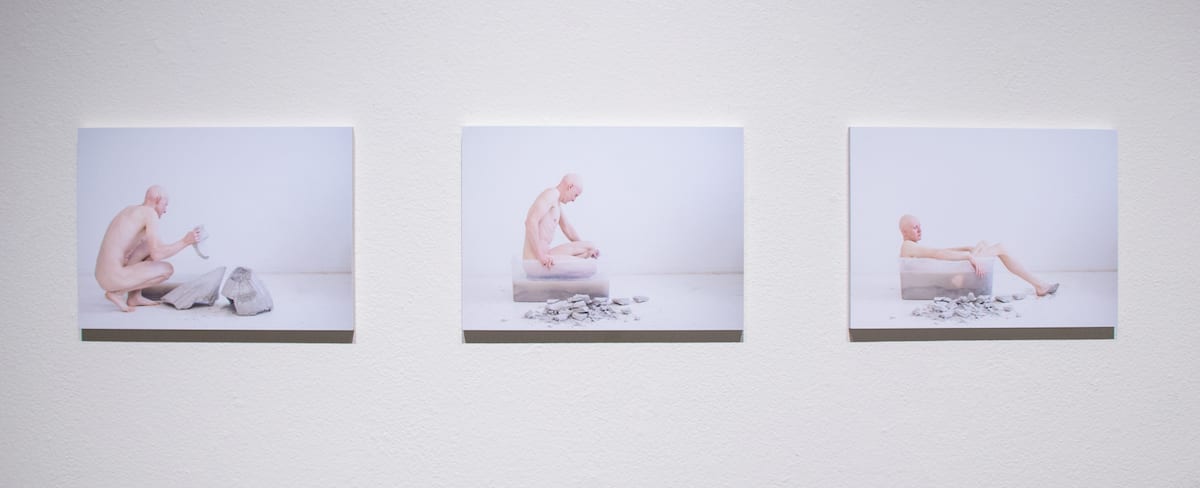

After visiting the exhibition, it became apparent to me that Qwist had used his time in the desert as a period of growth. On either end of the gallery were two series of photographs that give an example of the effect that this period has had on him. Of these photos Qwist writes:

“The two triptychs in the show, The Eleventh Hour and Slake, act as bookends. The exhibition is laid out so the viewer feels a sense of transition from one end of the room to the next. Eleventh hour has an urgency to it. An implied sense of impending loss or destruction that is relieved, at the last second. This is referring to my own constructed facade, held in place to guard me from vulnerabilities or the potential consequence that can come with transparency. Slake, offers up the antithesis to this idea. Naked and unguarded, I literally bathe in the reconstituting version of a piece that I blew up in the kiln. Owning my mistakes and nourishing my body with the lessons learned.”

The message here is that coming to terms with one’s faults, insecurities and the coping mechanisms one may use to counteract these difficult aspects of life can be painful. Though it may be difficult, this path leads to a more honest and genuine fulfillment of the human experience. In a world of insatiable vanity, toxic masculinity, this message could not be more poignant.

––Patrick Kingshill is a ceramic artist and designer who lives and works in Santa Fe, NM.

About the artist: After years working alongside his dad at the family bronze foundry, Joseph received his BFA from Colorado State University and his MFA from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. In 2016, he was selected as an emerging artist by Ceramics Monthly and awarded a summer residency at the Archie Bray Foundation in Helena, Montana. Most recently, he was living in Southern California where he taught sculpture and ceramics at the University of Redlands and Chaffey College. Joseph has shown nationally and internationally, and last year was commissioned to create public works for the Davidson Sculpture Garden in Riverside, California and the New Belgium Brewing Company in Fort Collins, Colorado.

Add your valued opinion to this post.