Milan Expo (May 1 – Oct. 31, 2015) got off to a rocky start this year. Its theme “Feeding the Planet, Energy For Life,” seemed good-natured, but its opening was marked by May Day protests in which demonstrators smashed windows and set cars on fire. There were more-peaceful protests. There was a group called “No Expo,” who question the event’s partnerships with corporations who, the demonstrators say, give the lie to the stated theme for that year. Such was the perceived contradiction that Pope Francis challenged the theme in his opening remarks prior to the Expo, warning about a “culture of waste.”

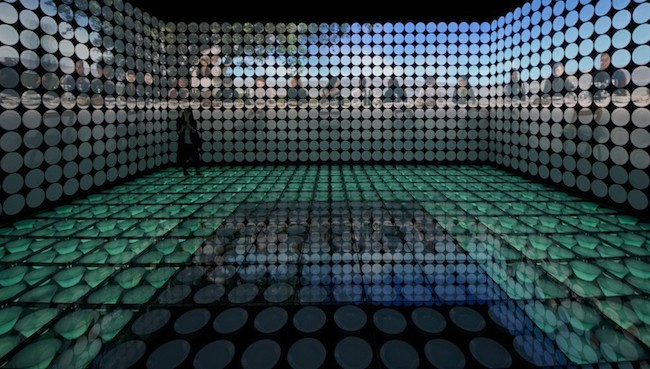

Above image: Antoni Miralda installation at Spain’s pavilion in Milan Expo 2015

We mention this because it provides some current events background to the work done by multimedia artist Antoni Miralda for Spain’s Pavilion. Miralda, the acclaimed food artist, created a display that the pavilion’s curators call El Viaje del Sabor (“The Voyage of Flavor”). The theme sounds like an aborted ad campaign from Red Lobster, but the goal was to create a range of activities that targeted the senses, with a focus on Spain’s diverse cuisine, sustainable farming and tourism.

Visitors to the pavilion first encountered a series of suitcases leading up to the entrance. From the pavilion:

“After this first encounter, a series of real-sized suitcases will guide visitors towards the Pavilion, transforming the main access into a kind of airport where ideas and information about food move around constantly. Once inside, the exhibition invites visitors to join the journey of certain products through a series of video setups that can be watched separately or as a group. A delicate and generic journey through Spain which, according to the artist, is “a cornucopia of the history of food”.

“To enhance the evocative power of each suitcase, the artist Antoni Miralda relies on the musical support of original compositions by Pablo Salinas, which seek to immerse spectators in a journey through Spain’s musical diversity and influences. Visitors will be able to interact with the exhibition, answering questions relating to food through a series of words appearing on the suitcases.”

We’re puzzled with the pavilion’s PR regarding the piece because the suitcases aren’t the coolest thing we’ve seen from the installation. We’ve come across photographs from Milan that show an enormous room lined with grids of what appear to be plates. What follows is an audio video experience that, although it puts us more in the mind of clubbing than eating, looks fascinating. It reminds us of an earlier Miralda work from 1989, Santa Comida. The piece is based in Afro-Caribbean culture and its legacy, with a focus on food. From the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona:

“Holy Food consists of seven holy altars dedicated to the most prominent Orisha deities. As the viewer moves around the installation, every altar reveals an image of a Yoruba deity and its equivalents in Christian worship. A number of foods and food products linked to the Yoruba gods frame the altars: Osun eats boiled sweet potato, fried bream, cakes and pineapple; Babalu Aye eats cooked quail, sugar cane, peanuts and coconut milk; and so on for all seven deities. A colour for every altar reinforces the link established with the various gods, while maintaining the colourful and sensorial elements of Miralda’s work. The artist awarded the god Eleggua the colours red and black; Oggun green; Yemaya blue; Obatala white; Shango red; Osun yellow; Babalu Aye pink. The installation is completed by soup tureens, objects wherein the Yoruba usually keep stones as a symbol of the strength and spirit of the gods, and other utensils and religious imagery related to the rituals of Santería. Finally, the work is accompanied by the song Angelitos negros (Black Angels), which in its bolero version made famous by Antonio Machín became a hymn against racial discrimination.”

Antoni Miralda, Santa Comida (Holy Food), 1984-1989, diverse materials, variable dimensions. Click to see a larger image.

The earlier work uses food to wrap up ideas of politics, the dismantling of prejudices and an embracing of different cultures. These are conveyed through participatory acts by the audience in the accessible mediums of kitsch and neon. These are all inclusive intentions, designed to reach out to masses of people. We wonder whether the protestors’ grievances would be better addressed with this work rather than the one in Milan. The work at Spain’s pavilion certainly celebrates food and culture but (and perhaps it’s just the suitcases) it seems more directed at tourism. A “delicate and generic” celebration of Spain’s cuisine is fine, but that doesn’t add much to other conversations that could be had about food. Miralda has the ability to make those kind of difficult observations happen. His work can get under people’s skin, just like it did in 2002 with The Catholic League.

What do you think? Let us know in the comments.

Bill Rodgers is a Contributing Editor at CFile.

Antoni Miralda, Santa Comida (Holy Food), 1984-1989, diverse materials, variable dimensions. Click to see a larger image.

Installation views of Antoni Miralda & Food Cultura, Reliquaire cyclique, 2014. A selection of table bells and jugs from the Musée des civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée collection as well as gourds, Caganer figurines and a jug from the artist’s collection. Miralda pictured above.

Add your valued opinion to this post.