The following is an essay by Russell Panczenko, director of the Chazen Museum in Madison, Wisconsin. The essay was included in the catalogue for the Chazen’s 2014 exhibition of sculptural works created between 1978 to 1979 by artist Michael Lucero. Panczenko characterizes this body of work as Lucero’s “Interlude” period, a time where he briefly digressed from ceramics.

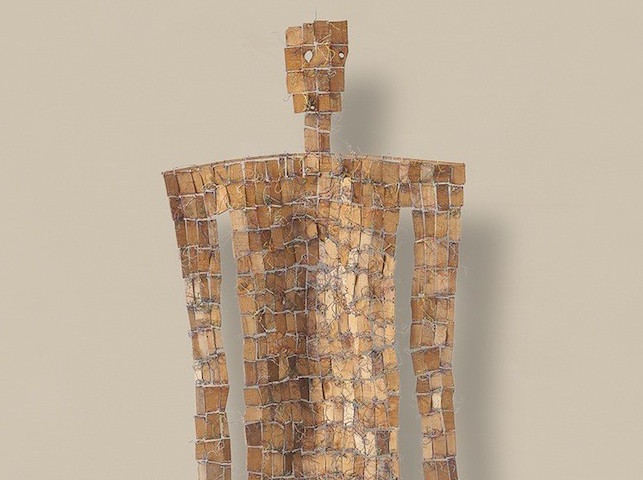

Above image: Michael Lucero, Untitled (7 inches), 1978 – 1979, wood, wire, 107 x 36 x 2 inches. Gift of Stephen and Pamela Hootkin.

Michael Lucero is one of America’s best known and respected artists in the clay medium. Over the years, his work has been the subject of numerous exhibitions and publications. A particularly significant event was the 1996 exhibition organized by Mark Leach at the Mint Museum in North Carolina. This exhibition, which subsequently traveled to a number of major museums around the country and was accompanied by a scholarly and well-illustrated catalog, firmly established Lucero’s reputation as a leader in the clay medium. In it the catalog, the author mentions a brief interlude in the artist’s career during which he strayed away from his beloved medium. Although, the work produced during this moment had been largely lost from critical consciousness, a recent act of generosity by Stephen and Pamela Hootkin to the Chazen Museum of Art at the University of Wisconsin–Madison has happily brought back to light some fascinating treasures of the past.

Michael Lucero, Untitled (Green Figure), 1978 – 1979, wood, wire, wax, paint, 120 x 47 x 4 inches. Gift of Stephen and Pamela Hootkin.

In 1978, upon completion of his MFA at the University of Washington, Seattle, Michael Lucero moved to New York City. There, he continued the series of larger-than-life human figures that had dominated his work for at least two years. However, without immediate access to a kiln, in 1978–79, he instead constructed a series of seventeen hanging figures from fragments of discarded fruit crates, broom and mop handles, and telephone wire scavenged in the streets of the East Village and Chinatown.

Like the figures in clay, the wood and wire New York figures are monumental in stature, each one somewhere between ten and twelve feet in height. Also, like the clay figures, they do not stand on the floor or on a pedestal. Rather each one is suspended from the ceiling by a wire thin enough to be almost imperceptible.

Lucero conceived of each figure as an individual sculpture. However, in their first public presentation at the Fine Arts Center at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (January 16 –February 8, 1980), the seventeen figures were allocated an entire gallery and installed as a group. The singularity of the subject matter and the artist’s experimentation with a new medium lent themselves to such a presentation. Also, as the artist pointed out to me in a recent conversation, he did not work on the figures one at a time. There were several suspended in his studio simultaneously and he would move from one to the other as he saw fit. For him the figures were like members of a family or a tribe and therefore it was appropriate that they should be introduced to the world as a group.

Michael Lucero, Untitled (Blue Glow), 1978 – 1979, wood, wire, wax, paint, 121 x 46 x 4 inches. Gift of Stephen and Pamela Hootkin.

After the exhibition in North Carolina the wooden figures returned to hang in the artist’s studio where they remained for a year or two, or until the space was needed for new work. Somewhere during this early period, Dorothy and Herbert Vogel, who were frequent visitors to Lucero’s studio, acquired two of the figures. In 2008-09, as part of their Fifty Works for Fifty States (50×50) program. The couple donated one of the figures to the Montclair Art Museum in Montclair, New Jersey, and the other to the Portland Museum of Art in Portland, Maine.

There the figures were occasionally integrated into displays of permanent collections. However, for the most part they remained in storage. The installation of all seventeen figures was never repeated. And, as Lucero’s importance and prestige as a ceramic artist became ever more firmly established, the brief interlude, during which he experimented with a different medium disappeared not only from view, but also from most peoples’ memories. Most, but not all.

Michael Lucero, Untitled (Homage to JP), 1978 – 1979, wood, wire, paint, 129 x 38 x 5 inches. Gift of Stephen and Pamela Hootkin.

In the fall of 2012, Stephen Hootkin, a connoisseur of contemporary ceramic arts and an avid collector of Lucero’s work, asked the artist about the fate of these figures and expressed interest in possibly acquiring one, if they could be located. Upon learning that the artist still had fifteen of them in storage, Hootkin together with his wife Pamela, committed to all of them sight unseen, and, immediately, offered them to the Chazen Museum of Art at Hootkin’s alma mater the University of Wisconsin–Madison. It was indeed a generous proposition.

The fifteen figures arrived at the Chazen in April 2012 from a warehouse in Northampton, Massachusetts, where they had been stored. The “sight-unseen” comment above is not as off-the-cuff as it may seem. Few, if any, of the individual figures had ever been photographed and we only knew of one black and white image of the group installation in 1980 taken by the artist himself. Unpacking the sculptures, once they arrived in Madison, was an exciting rediscovery for all involved.

In spite of having been in a warehouse for several decades, the figures were in relatively good condition allowing them to be hung up and photographed. The next question to be addressed was that of storage. Given their individual heights of eleven to thirteen feet, the artist suggested that we hang them up as if in a closet. A visiting conservator, on the other hand, recommended laying them flat since hanging would, over time, stress the wires holding them together. Given the museum’s prioritization of art preservation, it allocated the necessary square footage in art storage and constructed customized stackable platforms, one for each figure.

Michael Lucero, Untitled (Black and White), 1978 – 1979, wood, wire, wax, paint, 127 x 34 x 5 inches. Gift of Stephen and Pamela Hootkin.

It was also decided that one of the figures should be put on view immediately. Selecting one piece out of the fifteen was challenging, however, as there was no isolated spot where it could be hung by itself. Instead it had to be integrated into a densely packed gallery containing a selection of the museum’s art holdings of the last quarter of the twentieth century. Wherever the Lucero figure went in Gallery XIII, it would interact visually with several of other works on view. Ultimately, Untitled (Red Twister), Accession No. 2013.44.11, was selected even though it is formally distinct from most of the other Lucero figures – only one other piece in the group, Untitled (Twister) Accession No. 2013.44.10, is formally similar. Surprisingly, Lucero’s Untitled (Red Twister) partnered well with the painting Untitled, 1968 by Mark Rothko (Accession No. 1992.190) and Sol IV, 1967 by Richard Anuskiewicz (Accession No. 68.2.3); artists whom one does not normally reference in discussions of Michael Lucero’s work. What they all have in common is that the longer one looks at them the more dematerialized they become. The methods of achieving this optical illusion differ from artist to artist: Rothko uses the softness of color and the absence of any clear linear references; Anuskiewicz, on the other hand, uses hard lines, complimentary primary colors and geometry. Lucero’s two Twisters achieve this same visual effect by eschewing clear figural outlines and the negating of bodily substance. The wooden slats that comprise each figure are spaced in such a way that one sees right through it, hence they become ghost-like; they are both there and not there at the same time.

Michael Lucero, Untitled (Square Chest), 1978 – 1979, wood, wire, wax, paint, 108 x 31 x 5 inches. Gift of Stephen and Pamela Hootkin.

Another one of the figures Untitled (7 inches) Accession No. 2013.44.5 seems to draw inspiration from jade burial suits recently discovered in China and published in the popular press. Interestingly, this particular figure is one of only two with any indication of gender. Both have penis. All the others are unequivocally gender neutral. Although, in retrospect, one understands that the Twisters, as well as Untitled (7 inches), represent anomalies among the wooden figures of 1978-79, such observations pointed to some of the difficulties that might be encountered trying to think about this group of wooden figures in terms of Lucero’s overall oeuvre.

The Chazen Accessions Committee approved acceptance of Lucero’s figures in November 2012 and shortly afterward it was deemed that an exhibition of all of the figures was the appropriate way to introduce this generous gift to the university and Madison’s art community. Furthermore, if one were to exhibit fifteen of them, then why not reunite all seventeen in an installation similar to that of 1980. However, since there were no floor plans or easily decipherable photographs of that installation, it would in essence have to be redesigned at the Chazen by the artist himself.

Michael Lucero, Untitled (Twister), 1979, wood, wire, wax, paint, 125 x 57 x 2 inches. Gift of Stephen and Pamela Hootkin.

The question of combining individual works by an artist into an “installation” is an interesting one. Judy Pfaff, for example, when asked to assist in the design of a retrospective exhibition of her work at the Chazen in 2003, assembled individual drawings or prints into installations. These installations in effect, a common phenomenon in Pfaff’s exhibitions, became unique, if transitory works of art by the artist. Following the exhibition, the individual pieces were dispersed, and, the installations would vary from exhibition to exhibition depending on which individual pieces were available. In the case of Lucero’s wooden sculptures, given that they were representations of human figures to be contained at the Chazen in a single space, their arrangement could and would suggest a narrative. It was felt that the direction of that narrative implied or otherwise, should be the artist’s and not belong to the museum’s exhibition designer. In January 2013, Lucero, together with Meghan Mackey, a conservator specializing in contemporary sculpture, were invited to Madison to review the works and consult on the project.

Although the figures were in good condition, a couple of decades lying flat in storage had taken their toll. Ms. Mackey recommended that prior to the exhibition the sculptures be dusted and vacuumed, that the decorative plastic-covered telephone wires be rethreaded where they had come away, that all structural wires be checked to see that they were securely twisted, and that the metal staples that had separated be secured. Also all the figures were to be fitted with new 1/32″ aircraft cable for hanging from ceiling prior to being displayed. Kate Wanburg, one of the museum’s preparators, implemented the conservator’s recommendations in March–April 2013, several weeks prior to the exhibition.

Michael Lucero, Untitled (Aqua-Blue Man), 1978 – 1979, wood, wire, wax, paint, 131 x 45 x 4 inches.

From an art dealer’s perspective, a return to a living artist’s early work is not particularly desirable, however, for the museum curator it is an important learning opportunity. Also, for Lucero, the idea of an exhibition of the early wooden figures was a welcome one. He had long since moved on and, in fact, had not visited the 1978-79 wooden figures for quite some time. On seeing them as they were brought out of their storage bins for examination, he said: “It was as if I had made them yesterday.” He wholeheartedly approved the idea of the proposed exhibition with the inclusion of the two figures owned by the other institutions, and agreed to return in early May to direct the installation.

At Lucero’s request, a temporary wall was constructed in the Rowland Gallery, where the figures were to be installed so that the visitor would first encounter the installation from a central, frontal viewpoint. For the artist, this was the privileged viewpoint for looking at the installation as a whole. This was the point from which the installation was to be photographed. In regard to the placement and distribution of the individual figures in the gallery space, there was no predetermined floor plan. Rather the artist, for the most part, approached this empirically. Perhaps coincidentally, the figure that was central in this installation – and was the first to be put up in Madison at the artist’s request – is also the central figure in the only extant photograph of the earlier installation in North Carolina, even though that photograph shows the room itself on a diagonal. The other figures were introduced one at a time from front to back. The only guiding principle, besides the artist’s eye, was that formally similar figures not be juxtaposed. Equally important to the artist was the height of each figure from the floor, which was to be no less than one inch and no more than two.

Michael Lucero, Untitled (Twister) (detai).

Although the colors applied to the various pieces of wood comprising the figures had remained fresh during their years in storage, the ubiquitous plastic-coated telephone wires that both helped to hold the wood fragments making up each figure together and served as a vital decorative element had been pressed flat. When the pieces were displayed, Lucero insisted that these wires be “fluffed out.” The artist’s insistence on this factor became quite evident in the exhibition itself. These colorful cilia, for lack of a better term, visually enriched by the spot lighting, effectively extended and interlocked each figure with the surrounding atmosphere of the gallery itself. And, in fact they implied a reaching out, even if a frustrated one, to the other figures contained in the same space.

As one entered the exhibition, which opened May 10, 2013, the silence in the room where the seventeen figures were installed was profound. Even the most seasoned museum visitor lowered his or her voice to a whisper. One felt like an intruder into a congregation of supernatural beings, a benevolent tribe of giants, awesome and intimidating because of their stillness and monumentality. The installation of the seventeen figures elicited strong emotions. One visitor equated the experience with walking into a cemetery. The visitor definitely felt transported to another place.

Michael Lucero, Untitled (Pink Figure), 1978 – 1979, wood, wire, wax, paint, 115 x 34 x 5 inches. Gift of Stephen and Pamela Hootkin.

Occasional movement of the figures further affected the atmosphere in the room. For the most part, the figures remained motionless, but occasional disruptions in airflow, caused by the movement of visitors or the changing cycles of the HVAC system, made them rotate. They moved slowly. And, after a while, the torque of the wire returned them to their original position. This slight movement evoked the feeling that the figures were somehow alive. One the one hand, the casual slowness of the movement reassured the visitor that these giant figures, into whose space one has entered, were not threatening. On the other hand, since they could move at all, the question of whether or not they could move quickly and aggressively, if they wanted to, lurked in the back of every visitor’s mind.

I asked the artist about the sequence of the wooden figures. The intervening three-plus decades were for the most part insurmountable. All he could say was that he worked on many of them simultaneously. However, indulging in a little analytical speculation, one wonders if the seven figures, including the two Untitled (Twisters), that have broad bodies (in five of them, the wooden tiles are extended over a chicken wire mesh) came first. In this regard, they are similar to Lucero’s early figures in clay, such as Untitled (Adam and Eve) (1978) and Untitled (Devil) (1977) that were produced before his move to New York. The remaining ten figures are ultimately stick figures; one of them being so minimal as to be composed entirely of broom or mop handles whose surfaces have been decorated with magazine illustrations. Although in this last group the broom handles are densely covered with accretions of broken and painted wooden tiles, they are still basically stick figures. As to why the change, one can perhaps speculate that the stick-figures lent themselves more naturally to appreciation in the round, while the earlier ones were primarily frontal. It is also interesting to note that when Lucero returns to producing the figure in clay, they follow this latter formula, except that the wooden tiles have become “shards.”

Michael Lucero, Untitled (Big Hips), 1978 – 1979, wood, wire, wax, paint, 121 x 27 x 5 inches. Gift of Stephen and Pamela Hootkin.

It is interesting how an artist’s choice of words can sometimes get in the way of understanding his/her artistic development. Lucero has always talked about the use of “shards” in his early figurative work making no distinction between the figures such as Untitled (Hanging Ram) and Untitled (Devil) respectively of 1976 and 1977 that were produced before the interlude of 1978-9 and those produced after, i.e., Untitled (In Honor of the S.W.) and Untitled (Lizard Slayer) of 1980. Although Lucero says that both of these groups of clay figures are made up of “shards,” in the earlier clay figures the pieces of which they are comprised are not strictly speaking “shards.” In Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary, 1977, “shards” are: “fragments of pottery vessels found on sites and refuse deposits where pottery-making peoples have lived; a piece or fragment of a brittle substance.” In the pre-wooden New York work the “pieces” or “shards” comprising each figure were individually modeled organic forms, often leaves. When Lucero returned to producing his monumental figures in clay, the individual components were no longer realistically modeled, rather, they had become broken pieces of pottery, specifically fabricated as such by the artist.

Artists draw inspiration from all kinds of circumstances. During Lucero’s visit to Madison in January 2013 to review the wooden figures and see the gallery where they would be installed, I pointed out that there was an adjacent gallery. Rather than leave it fallow, I wondered out loud if there were any drawings in his possession that related to the figures in some way. Two months later, Lucero informed me that he was working on a new series of drawings inspired by “my challenge,” and asked if I would consider including some of them in the exhibition. In a relatively brief time he had produced over forty drawings, which, when they arrived, proved to be different from anything that he had done before. Again, like the wooden figures of 1978-79, this body of work allowed some insight into the workings of the artist’s mind.

The realization of the wooden figures of 1978-79 was very intense, requiring hours of conceptual thought and physical labor. For a young artist, straight out of school and finding himself in a new and exciting cultural environment, 1978-79 was an intense period of exploration and experimentation. The circumstance of not having a kiln at his immediate disposable probably provided a certain degree of freedom. He had already decided that clay would be his métier but for the moment he could try whatever came to mind.

Michael Lucero, Untitled (Red Twister)(detail), 1979, wood, wire, wax, paint, 120 x 49 x 2 inches. Gift of Stephen and Pamela Hootkin.

The drawings done in the spring of 2013, on the other hand, show a degree of spontaneity and a speed of execution that are not found in his wooden figures or, for that matter, in his subsequent clay work. In large measure, this is the difference between a young artist trying to find his way and a mature artist with the confidence of a long record of achievement. However, I would imagine that the specific circumstances of 2013 also engendered a moment of artistic freedom for Lucero. He did not have to self-consciously advance the next step in his career. Instead, he was confronted with an exciting moment from his past, a moment that he was surprised to find “as fresh as when I did them.” And, he could not help but remember his primordial fascination with the totemic human figure that had originally inspired him.

All the drawings are on 40 x 28 inch sheets of seamless brown cardboard, a stack of which the artist had acquired some time earlier at an estate sale. He used ordinary objects he found around the house, for example, a sponge, his child’s shoe, a plastic butterfly-shaped fly-swatter, the end of a roll of toilet paper, both with and without the paper on it, CDs, etc. He dipped these tools into acrylic ink and dabbed marks on the paper. Each drawing was done quickly and intuitively. The selected medium did not allow otherwise. A drawing either worked for Lucero or it didn’t, in which case it was discarded.

The subject of each drawing in this series is the human figure. Most of them depict only one figure; a few, two figures; and fewer still, three. Although Lucero indulged in few moments of radical experimentation in this series—a snowman-like figure composed of three spheres, or one with arms drawn with a rare gestural mark—most of the figures are rigid and stand frontally to the viewer. Some of the figures are decidedly masculine with broad shoulders, bulky physiques, and aggressive postures. Others are humorous and even clown-like. In one the subject seems to be a family: mother, father, and child.

Michael Lucero, Untitled (Red Twister), 1979, wood, wire, wax, paint, 120 x 49 x 2 inches. Gift of Stephen and Pamela Hootkin.

Although a few of the figures in this series resemble the stylized stick figures of the early period, most of them have broad flat torsos, probably because they are decidedly two-dimensional drawings. They are not intended as preparatory drawings for sculpture. This series represents an interesting moment for an artist who spent most of his career producing three-dimensional work.

In six of the drawings Lucero superimposed a second figure over the first by cutting it out. The contrast between the white ground on which the drawing is mounted and the brown paper of the drawing itself gives the secondary figure a strong if ambiguous location in the composition. One is unsure if the secondary figure is inside the drawn figure, an inner skeletal reality so to speak, or some kind of spectral presence standing between the viewer and the drawn figures. The viewer’s understanding vacillates back and forth between these two views and does not seem to want to be fixed.

One final work pertaining to this series of drawing needs to be mentioned. Adjacent to the temporary exhibition galleries are the museum’s loading dock and receiving area. A door measuring 15 x 9 feet provides passage between the two areas. In the gallery itself the door is surmounted by a hinged wall surface so that it may be used for the display. However, a cherry wood frame clearly demarcates this section and in effect interrupts the continuity of the gallery’s display surface. Lucero creatively turned this architectural challenge to his advantage. Asking that the hanging wall surface of this door be painted to match the color of the cardboard sheets on which the drawings were done, he turned the entire door into a monumental site-specific work of art. Over the course of a couple hours, using the same daubing technique as that of the other drawings, he drew two colossal standing figures, which confront the viewer as upon entering the gallery from the opposite side of the room.

Interestingly, Lucero did not want the museum visitor to see the drawings before experiencing the wooden figures. For him the visitor’s sequential progress from one to the other was very important. Thus the drawings should perhaps be seen as an afterthought, a kind of nostalgic return to a theme and a time that was particularly meaningful to the artist and his work.

Michael Lucero installation view.

In our commercially driven art world, it is difficult for an artist to digress from an established identity. For a young artist such as Lucero who ascended to stardom very early in his career, experimenting with a new medium is especially problematic. Hence, the relative disappearance of the fascinating wooden figures Lucero produced in 1978-79. Happily, art historians and museum curators, in large measure, are sheltered from the vicissitudes of the art market, and can indulge in intellectual curiosity. The Chazen was particularly pleased to have the opportunity to explore this important interlude in the artist’s ceramic career and perhaps shed some light on the workings of this wonderfully creative artist’s mind.

Thank you again to Stephen and Pamela Hootkin for making it all possible.

Russell Panczenko is the Director of the Chazen Museum.

Any thoughts about this post? Share yours in the comment box below.

Add your valued opinion to this post.