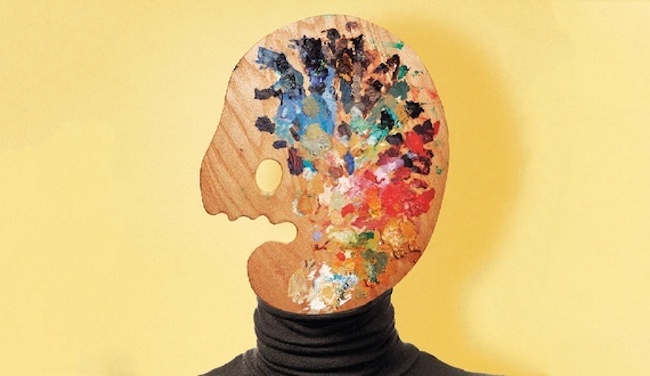

“Pronounce the word artist, to conjure up the image of a solitary genius. A sacred aura still attaches to the word, a sense of one in contact with the numinous. ‘He’s an artist,’ we’ll say in tones of reverence about an actor or musician or director. ‘A true artist,’ we’ll solemnly proclaim our favorite singer or photographer, meaning someone who appears to dwell upon a higher plane. Vision, inspiration, and mysterious gifts as from above: such are some of the associations that continue to adorn the word.

William Deresiewicz writing in The Atlantic (December 28, 2014) makes a compelling point that the time of the artist as a sanctified creator, above the petty obsessions of mankind (like money), a seer answering only to their muses, may be coming to an end if it was not just a passing mirage to begin with. Successful artists used to run modest studios, there they grew larger in workshops and now, for some, they are art factories. The following is an excerpt from his brilliant analysis. Keep reading at least until you reach his concept of “producerism” a democratic but frightening concept for the professional maker and a warning that artists are again soon going to be known as crafters.

There’s some shock, maybe even indignation, that follows whenever a critic makes a pronouncement as large as Deresiewicz’s. We think that the concept of the artist, as we know it, is something that’s been with us forever and so his piece seems like an attack on culture itself. However, history is more nuanced than that. As he explains:

“All of this began to change in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the period associated with Romanticism: the age of Rousseau, Goethe, Blake, and Beethoven, the age that taught itself to value not only individualism and originality but also rebellion and youth. Now it was desirable and even glamorous to break the rules and overthrow tradition—to reject society and blaze your own path. The age of revolution, it was also the age of secularization. As traditional belief became discredited, at least among the educated class, the arts emerged as the basis of a new creed, the place where people turned to put themselves in touch with higher truths.”

Much of what defines our concept of what it means to be an artist is determined by access, he argues. Artists are shown in museums and galleries, they are awarded residencies, people like ourselves start the discussion of what work you should be paying attention to and why. He argues — broadly, but it’s a broad topic— that these are bureaucratic institutions from an earlier time. With the Internet everyone has a potential audience. And even though we know fantastic artists who are still languishing even though they can be their own hype machines, the dynamics have changed.

“What we see in the new paradigm—in both the artist’s external relationships and her internal creative capacity—is what we see throughout the culture: the displacement of depth by breadth. Is that a good thing or a bad thing? No doubt some of both, in a ratio that’s yet to be revealed. What seems more clear is that the new paradigm is going to reshape the way that artists are trained. One recently established M.F.A. program in Portland, Oregon, is conducted under the rubric of “applied craft and design.” Students, drawn from a range of disciplines, study entrepreneurship as well as creative practice. Making, the program recognizes, is now intertwined with selling, and artists need to train in both—a fact reflected in the proliferation of dual M.B.A./M.F.A. programs.”

Which brings us to the slightly depressing part of his piece: Marketability and what that means for the field lurks a little more brazenly. If anyone can create and this creativity can be accessed by anyone, how do you become successful? How do you rise above the millions of other creatives who have not only the same tools at their disposal, but also the ability to casually dismiss critical scrutiny? With social media we can see the artist’s process, outside interests and personal life. Are we then consuming the work or the person?

But if this is where the current trends are leading us, it seems pointless to waste precious time wringing one’s hands over or fighting it. The zeitgeist isn’t good or evil, it just is. There’s a certain amount of comfort to be found in upheaval. It means you get to witness or even participate in something new as it takes shape. Ask yourselves: How much fun was the old model really?

“Creator: I’m not sure that artist even makes sense as a term anymore, and I wouldn’t be surprised to see it giving way before the former, with its more generic meaning and its connection to that contemporary holy word, creative. Joshua Wolf Shenk’s Powers of Two, last summer’s modish book on creativity, puts Lennon and McCartney with Jobs and Wozniak. A recent cover of this very magazine touted “Case Studies in Eureka Moments,” a list that started with Hemingway and ended with Taco Bell.

“When works of art become commodities and nothing else, when every endeavor becomes “creative” and everybody “a creative,” then art sinks back to craft and artists back to artisans—a word that, in its adjectival form, at least, is newly popular again. Artisanal pickles, artisanal poems: what’s the difference, after all? So “art” itself may disappear: art as Art, that old high thing. Which—unless, like me, you think we need a vessel for our inner life—is nothing much to mourn.”

Read the full essay in The Atlantic.

Bill Rodgers is a Contributing Editor at CFile.

Any thoughts about this post? Share yours in the comment box below.

It appears to me that the point of this article has been completely missed here. This is not just an acknowledgment of where we are as “creatives” or “where the current trends are leading us.” One should not find comfort in conforming to this. This is a warning, that if we lose Art, we may lose the one thing that allows us to think critically, show a mirror of society onto itself, and express ourselves emotionally.

The obvious stance is in the sardonic statement, “ ‘art’ itself may disappear: art as Art, that old high thing. Which—unless, like me, you think we need a vessel for our inner life—is nothing much to mourn.”