The nice thing about Robert Arneson’s 1981 masterwork, Portrait of the Artist as a Clever Old Dog that comes up for auction in a few days, is that years from now one can easily find out what it sold for. (The estimate was ludicrously low, by the way, so don’t get your hopes up.) We will post the result on CFile. Why is this beneficial? It helps museums and collectors track prices for insurance, it provides a basis for appraisers to justify prices on tax-deductible art gifts (without this they have to get dealers to share invoices in recent sales, not an easy sell) and this practice goes back to the 19th century, allowing art economists to do long-term studies on the art market.

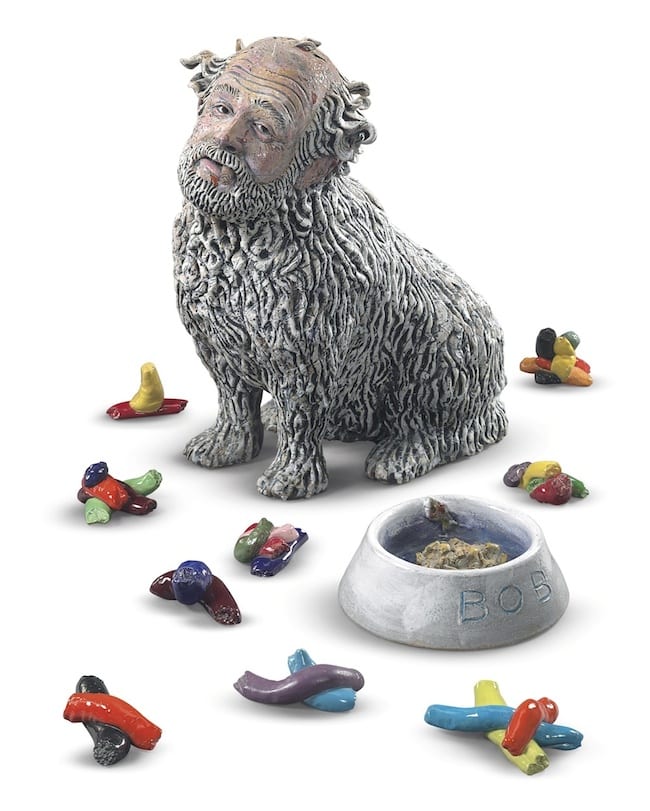

Above image: Robert Arneson, Portrait of the Artist as a Clever Old Dog, 1981. Eleven elements—glazed ceramic dog: 32 x 23 x 31 in. (81.2 x 58.4 x 78.7 cm.), bowl: 5 x 14¾ x 14¾ in. (12.7 x 37.4 x 37.4 cm.), each ancillary element: approximately 4 x 5 x 7 in. (10.1 x 12.7 x 17.7 cm.) Courtesy, Christies Auctions. Copyright Robert Arneson Estate

Of course there are those who do not like the practice, particularly minor dealers who buy on auction to quickly flip their purchases. But I believe that transparency in the marketplace is better for both ends of the transaction.

Christies has taken the first step to draw the curtain. Citing non-existent “industry standards,” a Christies spokesman told CFile that they will no longer reveal results on their online sales. Who benefits from this practice, one wonders? It’s difficult to name one other than the auction flippers. But this is a mixed blessing even for them. Yes, their client will not know what you paid so they can name whatever price they the market will bear, but in turn they will have no idea as to whether the price they paid was an anomaly, part of a rising or falling pattern. They are flying blind as well.

Why bother? For a journal like CFile that tracks the ceramic market’s movement this policy is particularity disturbing. Online sales tend to be for lower-priced items (although Christies online sales of Picasso ceramic editions can top $80,000 for a single lot). Studio pottery sales will almost all fall into this category.

Two works by Michael Cardew from Christies Auction, “20th Century Japanese and British Studio Ceramics,” (Cyberland, 14 October – 28 October, 2014). Any guesses as to what they sold for or if they sold?

Indeed, it was in trying to find out the result of Christies recent 20th Century Japanese and British Studio Ceramics (Cyberland, 14 October – 28 October, 2014) that this issue arose. It was a particularly stunning body of work. But we will never know whether it sold well in what is currently a depressed market, whether most works found buyers, or whether an amazing new record was reached for an artist. These facts are all key in discerning a market’s health. I later tried to find the catalog of the sale and could not access it either. Is this a glitch or is that a new policy as well? All evidence of the event has been erased.

If this example is followed online auctions will become a secret society. The decision was probably made carefully knowing that someone will benefit. Maybe its purpose is to dial the IRS out of the picture? Whatever the reason— and its not paranoid for me to say so— the beneficiary of this new policy is unlikely to be you or me. Bottom line: CFile intends to beat this drum long and loudly until the policy is reversed.

Garth Clark is Chief Editor of CFile

Any thoughts about this post? Share yours in the comment box below.

Posted by Christies – I heard the estimate was a typo – ROBERT ARNESON (1930-1992)

Portrait of the Artist as a Clever Old Dog

LOT 426

SALE 2893

PRICE REALIZED

$233,000

This is only the beginning, have you noticed how the images are beginning to diasppear from auctioneers websites? The paid online databases draw the information that they provide directly from the auctioneers sites so in turn, you’ll find that there are many gaps in the databases. Within auction and image copyright law there is a concession that allows auctioneers to use one image per lot to help sell the item, the auctioneers are not charged by the artist’s collection agency for this. However, a new and evolving interpretation of image copyright law promoted by the agencies that represent the interests of their artists and photographers has meant the introduction of charging for any additional use of images that feature the artist’s work, this includes catalogue covers, details, invitations to viewings, archive images showing the work in a historic setting, website homepages and now they are beginning to try to charge an additional fee for keeping the image online after the auction has completed. These costs add up, auctioneers are criticised for keeping 25% buyers premium plus maybe another 10-15% from the seller but in reality, the margins are often relatively tight when you consider these fees. Aside from the significant print and distribution costs the additional £450 charged to the auctioneer for use of a detail, and a further £150 to keep the image on the website after the sale has finished represent £600 or the full 25% buyers premium on a ‘hammer’ price of £2,400 Inevitably this forces either reduced presentation levels, or auctioneers to have to concentrate only on items selling way above that level. The consequences of raising this bar still further are inevitable.

I do not speak for Christies, and there may be other reasons for the works disappearing after the auction but I can imagine that one way of them maintaining a margin on the online sales would be to cut this fee out of the equation.

Hi Garth, There is one way of tracking online sale prices,that is to watch the sale as a live auction and note the final bids.While I visited the auction on several occasions ,noted that many pieces had no bids,I did not do this for the various closing times of the Christies auction as I thought I could look them up the next day .To some,information is power! Regards Colin

Please do beat that drum loudly.