The long overdue tribute and exhibition, What Would Mrs. Webb Do? A Founder’s Vision (New York, September 23, 2014 to February 8, 2015) is an example of what the Museum of Arts and Design should be doing more often: linking past, present and maybe even the future of handmade objects. The Museum is showing confidence, mining its own past. Indeed, the signs of positive change are appearing everywhere in things big and small, like a much peppier volume of Views.

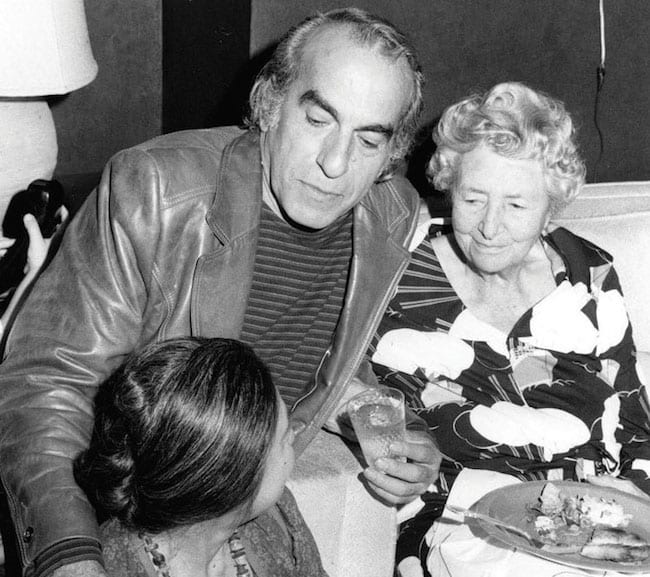

Above image: Aileen Osborn Webb in the early 1960s with Peter Voulkos and Toshiko Takaezu. Image courtesy of MAD.

Curator Jeannine Falino and her team have successfully delivered a carefully modulated show with good scholarship that addresses a long-overlooked but major figure in the contemporary craft movement. It gives context to where craft begins in the mid-20th century and takes us to where it is today. The look might be “stuffy” to quote New York Times critic Karen Rosenberg, who otherwise largely enjoyed the show, but I would call it “appropriately reverent” and like Mrs. Aileen Osborn Webb herself, low key.

She was a remarkable activist bluestocking, plain spoken, without any airs and a lifelong love not just of the crafts but what they could do in social good like providing work for women and income in rural areas.

What she would “do” today is an interesting question posed in the show’s title. What she would “say,” however, is more fascinating. The museum title is too obvious but that would have perplexed her. She revered the craft as an exceptional, humanist calling and the original name of the museum she founded is still perfect, Museum of Contemporary Crafts.

A couple viewing an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Craft, courtesy of MAD.

I met her twice in the early 1970’s and once had tea with her in her penthouse. It was more comfortable than grand, not shabby but lived-in. Without being impolite so was Mrs Webb; she was warm, motherly and gracious. One of our discussions was about the “radical” artist Peter Voulkos, with whom she was a close friend.

She said he was a genius but added, “but when he gets it wrong, boy does he get it wrong.” Underneath her benevolence was a sharp and critical eye but she rarely voiced her tougher opinions, seeing her role as a diplomat for the field worldwide, not a connoisseur.

As MAD states, Webb, as a patron and philanthropist, pioneered an understanding of craftsmanship and the handmade as a creative driving force behind art and design. The first half of the exhibition features work by American makers from the 1950s to the late 1960s whose practice directly benefited from the support of Webb and others who shared her vision, while highlighting the many crafts-related institutions that Webb launched, such as the American Craft Council, the School of American Craftsmen, and the World Crafts Council. These still form a vital support structure for today’s world of makers. What Would Mrs. Webb Do? also surveys the museum’s achievements under her direction with a focus on the landmark exhibition Objects: USA, funded by Johnson Wax and Karen Johnson Boyd, which opened in 1969 and traveled to 30 museums in the USA and abroad.

The second half of the exhibition is handsome but it feels uncomfortably political, like the “and we want to thank” at the end of a book. It features supporters who carry on Mrs. Webb’s vision today like board member Nanette L. Laitman. She has promoted the Museum’s mission in countless ways, providing support for the recording of 235 oral histories of American craftsmen by the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, excerpts of which are alongside key examples of some of their works of art.

The presence of the Museum’s most recent and celebrated acquisitions underscore the role played by the Windgate Foundation in shaping the current discourse on contemporary craft through its support of makers and non-profit institutions – the Museum of Arts and Design among them.

Mrs. Webb at the wheel. Photographs courtesy of the American Craft Council Archive.

Rosenberg particularly enjoyed the “Gold Medalists” section:

“Devoted to artists who were recognized by the American Craft Council in an annual prize first directed by Mrs. Webb. The honorees include the ceramist Beatrice Wood, the enamel artist June Schwarcz and the fiber artist Kay Sekimachi, whose delicate weaving of translucent monofilaments is one of the show’s standouts.”

What the exhibition does best is a create an environment and the individual works, although mostly very well chosen, are less important individually than the collective brio, allowing one to soak in the generally conservative (and often brown) mise-en-scène of the early post-War craft movement and to appreciate what it spawned.

For more insight into Mrs. Webb we suggest an excellent interview between Barbara Haugen and MAD’s curator Jeannine Falino on the American Craft Council website. Haugen comments that Webb “was born to wealth and married into more, but was never one to sit around polishing her pearls.” Actually in her class someone else would have done that anyway but the general impression is correct.

Bravo.

Garth Clark is the Chief Editor of CFile.

Any thoughts about this post? Share yours in the comment box below.

P.S. I, too, thought the museum did a fine job of interpreting the time period and institutional history through the objects collected by the museum. The installation reflected Mrs. Webb’s calm determination. Kudos to Jeannine Falino for her own determination to bring Mrs. Webb’s persona back to the New York marketplace.

You can also read my article about Mrs. Webb, her life and work, in the March 2013 issue of the Journal of Modern Craft (vol. 6, no. 1), beginning on page 11: “Aileen Osborn Webb and the Origins of Craft’s Infrastructure.”

I entered the show after the two floors of the MAD Biannual and suddenly CALM descended. Heart rate and blood pressure dropped noticeably. The installation was sort of fussy and old school, but it seemed just right. What a joy! Let’s hope there are more like this. Maybe we can even hope that one day there will again be a Museum of Contemporary Craft.