I’m not going to be coy: Camp Fires: The Queer Baroque of Léopold Foulem, Paul Mathieu and Richard Milette at the Gardiner Museum (Toronto, May 29 – September 1, 2014) was the finest ceramic exhibition to address LGBT issues yet. It was superbly curated by Robin Metcalfe and even if one takes away the propagandist tenor, it is a remarkable art event in its own right. The exhibition is one of a series of events that took place in Toronto’s major cultural institutions to celebrate WorldPride week.

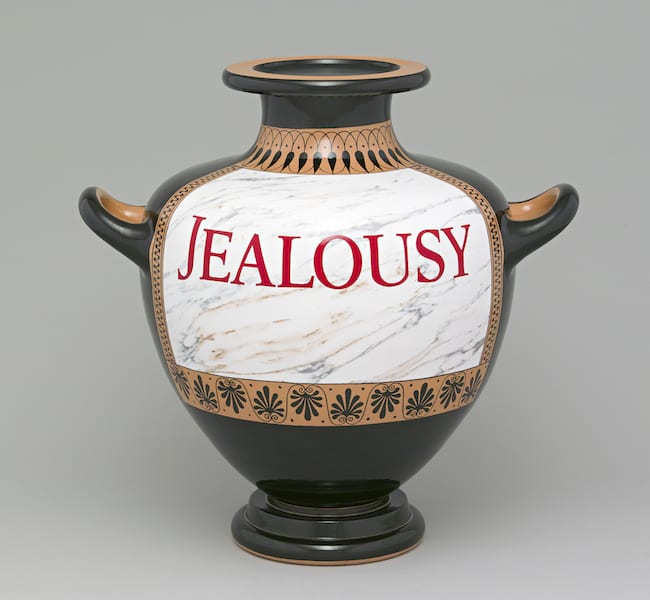

Above image: Richard Milette, Jealousy, 1997, earthenware, 39 cm height.

Léopold Foulem, Paul Mathieu and Richard Milette were born and grew up in Quebec. Mathieu and Milette studied with Leopold. Each is an artist in his own right, they do not collaborate on the same works, but they do comprise a close-knit incestuous collective. Added to that, Foulem and Milette are lovers.

Each is a formidable, opinionated scholar of ceramic history and Foulem and Mathieu are fiercely confrontational and vocal activists on gay and aesthetic issues. Millette, perhaps surrendering to the competition, rarely speaks. But they are not joiners and operate largely independent from the LGBT community. In other words, they are their own parade of three.

Leopold Foulem, Bicycle Seat Blue and Yellow, ceramic paint, found object, 43cm length.

I have been following their work since 1976 and am credited with coining the title “Quebecois Clay Movement” to describe their genre. Geographically it is adequate but not conceptually. And, in full disclosure, I appear with my partner several times in one of the artworks, including a portrait of us with friends at New York’s infamous Black Party.

I cannot be bought that cheaply. My closeness to the subject and artists has not prevented me from being a tough critic of the trio over the years.

The exhibition is an audacious step for a museum better known for its country club gentility. Critic Ben Kaplan, writing in the National Post notes this in the opening paragraph of his review, “Clay is (so) gay: How that slogan is rebranding The Gardiner Museum, just in time for WorldPride Toronto”:

“Parental advisory warnings outside a museum are something you might expect at the Tate or New York’s Gagosian, places that traffic in outlandish art. The Gardiner, Canada’s national ceramics museum, however, is about as likely to cause a ruckus as a second grade art fair in Moose Jaw. And yet, outside the entranceway to Camp Fires: The Queer Baroque, audiences are cautioned: “Warning: Camp Fires features adult content and explicit sexual themes. The most staid museum in the country is about to smash some crockery.”

This serves notice that Kelvin Browne, the museum’s new CEO and executive director, is willing to rattle the institution’s shards:

“This is a chance to broaden what we’re about as a museum. Camp Fire’s a stretch for the Gardiner, we’re a historical museum, but there’s a new mindset here on how we engage with the public. We’re enthusiastic about the chance to get people to look at us in a whole new light.”

The show is tougher than Kaplan allows: “A recent tour of the exhibit with two of the show’s three ceramic artists, Léopold L. Foulem and Paul Mathieu, proved witty and daring, yet surely not something where you’d need to lock up the kids”. If true that indicates a cultural divide between the more liberal, less secular Canada and the US.

Leopold Foulem, Pair of two male couples in a Pseudo Rococo Setting, 2012. Ceramic and found objects, 57 cm height. The artist chose this as his favorite work and discusses it in the attached video.

Here the doors would be locked and bolted if not because of sexual content then due to the trio unflinching assault on the Catholic Church and its sexual abuse of children (with Quebec’s scandals being the most egregious). Charges of obscenity might even reach the courts.

Foulem, the group’s de facto leader or guru, is particularly tough in this regard. In his figures he portrays priests in the guise of Santa Claus and (for some reason that escapes me) Colonel Sanders as molesters of a young idealized male beauty represented by Gainsborough’s Blue Boy.

Left: Priest in Black Cassock with Boy on Mount, 2012, ceramic and found object, 36cm height. Right: Leopold Foulem, Santa and Blue Boy (Gallant Conversation), 2004, ceramic, 21 cm height.

As with much of his work he places some of the figures within found ormolu. You will note in Gallant Conversation, which has the appearance of being molded in chocolate, that the hat the boy holds morphs into a condom.

Leopold Foulem, Banana and Cross, 1976, clay and mixed media, 70 cm height.

Even a portrait of a thorn-crowned and bleeding Jesus, usually sacred territory, gets perverse with a text that reads “I (heart) my daddy”, loaded language in gay circles. And what may be the most seditious piece in the exhibition, a crucifix with Jesus as a banana, peeled skins forming his arms.

The bananas, the most louche of the fruits (with the exception perhaps of the figs) are important to both Foulem and Milette. Indeed, if the banana did not exist, they would have had to invent it. Or use a cigar. Exhibit A: Juicy Banana by Foulem is a post-orgasm candy-colored banana in a puddle of cream on a metal platter.

Leopold Foulem, Juicy Banana, 1978, ceramic, found object, mixed media, 49.5 cm length.

Richard Milette, Vase “sirens” with Bananas, 1993, ceramic, 45 cm height.

Richard Milette, Cup on Fruits, 1998, ceramic, 17.5 cm height.

Bananas ennoble Milette’s Vase (sirens) with its faux gilded bronze ormalu. His Cup on Fruits, a seemingly innocent title except the double entenrde of “fruit,” makes its point very well and demolishes any innocence of language in this show. Everything becomes loaded.

Not that the pair have any fear of the real thing. Both are aggressively phallocentric artists and Milette extends this to his S+M work, Teapot for Queen X, a reference I assume to Robert Mapplethorpe’s infamous X Portfolio of 1978. Foulem’s Urinor (a nod to Duchamp) and urn Funereal are almost hardcore but at the same time, the epitome of elegance.

Richard Milette, Teapot for Queen X, 1989. Ceramic, 32 cm length.

Left: Leopold Foulem, Urinoir, 1992, ceramic and found objects, 60 cm height. Right: Urn Funereal, 1985, ceramic and found objects, 55 cm height.

Foulem also enjoys queering innocent images. One of his famille juane themed ceramics takes on Canada’s most revered icon outside the maple leaf, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. He gives their name (indeed one that is wide open for parody) a lewd twist with two policemen sharing one horse in a suggestive position.

Whereas Foulem’s art has more layers than baklava, Milette tends to speak through familiar icons, delivering his messages, not free of complexity, but the same time quickly delivered, broad and easily understood. Gold Marilyn a Greek hydria speaks to the gay obsession with divas, a key component of camp.

Another two in this series, Hydria with Love and Hydria with Hate have starkly different contexts in the hands of a gay artist. One address the love that in many parts of the world still cannot speak its name and the other is shorthand for homophobia, often deadly, two sides of the same coin.

Richard Milette, Hydria 13-7318 with Gold Marilyn Monroe, 1988, ceramic, 42 cm height.

Richard Milette, Hydria 13-6189 with Love, 1990, ceramic, 40.5 cm height.

Richard Milette, Hydria 13-4165 with Hate, 1994, ceramic, 40.5 cm height.

Speaking of hands, all three artists would prefer not to make their work and place no value on craftsmanship or labor although they are among the finest crafters of their generation. Their objects have impeccable finish, luscious surfaces, perfect firing, and tactile eroticism. Indeed in craft terms they are virtuosic. Whether this can be written off by them as a paradox or irony, its remains a material truth.

Paul Mathieu is a better craftsman than he seems to be. There is a deliberate edge of informality in his objects and he uses some affected clumsiness to mislead the average viewer. This gives his work a different voice to the sharp graphic quality of Foulem and Milette, but it speaks a common language nonetheless.

Like his compatriots he knows that the physical qualities of the object need to match the sophistication of its conceptual raison d’etre. As Grayson Perry once said to me, “ceramics does not allow one to remain amateur.”

Paul Mathieu, Untitled (Crucifixion Bowl) 1984, ceramic, 21cm diameter.

Unlike Foulem and Milette, who rely on the prurient mind to see more than there is, Foulem takes a shortcut, bypasses the suggestive and goes direct to tawdry. His bowl Untitled (Crucifixion Bowl) implicates Jesus, shown almost naked, sensually muscled and arching back in the curve of the bowl in a pose reminiscent of male porn.

Paul Mathieu, Camouflage series (E.M), 2005, porcelain, 73 cm height.

Both series, Camouflage and Pretty Boys (closeted and out) with their homoerotic bad-boy look (and a few less-appealing oddities), are awkward, almost clumsy vessels. Raw photography and ugly gold (I hope that was intentional, it is not flattering) are shown in a vulgar dime-store, baroque styling, a cliché of the shabby-chic, camp apartment, lots of faux-leopard skin and chintz.

Gay celebrities, literary and art figures are related to each image but identified by initials known only to the literate gay cognoscenti. “E.M.” is Forster, and is the gun a link to his policeman boyfriend (ignoring the fact that British police do not carry firearms)?

“AR” is the poet, Arthur Rimbaud. “MR” is Man Ray, (a red, not gay). The photograph on this piece is Male Torso, 1930, from his solarized series. This straight Dada artist becomes a deliveryman, offering what would later become a cliché pose of the gay muscle magazines of the 1950’s.

At the end, Mathieu’s art comprises everyone.

Paul Mathieu, Cute Boys Series, (M.R.), 2005, porcelain, 73 cm height.

His Kiss Vases 1-6, a set of six in three pairs, comprise the shows tours de force. On the front they are a masterful collage of gay imagery, much of it unassuming without any agenda, of happy couples, individuals, artists and friends. The layering is decoupage on steroids, masterful and beautifully resolved. Verso they are faces erupting with lips with each pair of vases locked in kisses.

They are unequivocally both pottery and art.

Paul Mathieu, Kiss Vase 1-6, 2013, porcelain, 40cm height.

Lastly, a few quibbles about Kaplan’s review. For a gay man almost any review of “gay” art (no matter the orientation of the writer) is going to raise one’s dander at some point. The language and understanding of LGBT is still too tender, bruised, personal, new, fragile and unresolved to escape semantic landmines.

The writer’s notion that “the world of modern ceramics belongs to gay artists, as evidenced by the Turner Prize awarded to British artist Grayson Perry in 2003. It’s 2014. It’s summer in Toronto. Are we really so shocked by gay clay?” is odd and unsupportable.

Firstly, his “evidence” is mistaken. Perry is a straight cross-dresser (they outnumber the gays ones). Camp? Yes. Gay? No. Bernard Leach and Hans Coper were womanizers. The most important single movement in modern ceramics was the Otis Clay Movement with a macho Peter Voulkos at the helm. One could not come across a more macho, camp-deprived crew. Ceramics is universal and while gay may have a niche it does not have ownership.

I have no problem with the posters in front of the Gardiner declaring, “Clay is (so) gay”. It is fun, adopting and thereby defusing the “so gay” slur. But a quote in the review from Bruce LaBruce, a filmmaker and artist, is unfortunate:

“Ceramics have always been a super gay form…A museum like the Gardiner ignores gay artists at its own peril. Not having an exhibit like this would just be a silly thing to do.”

Billboards in front of the Gardiner Museum.

Ceramics? Super gay? Really? This is, to use Labruce’s word, silly; thoughtless cheerleader hyperbole that is both meaningless and ignorant of the medium.

These quibbles aside, the show is sensational in all the right ways, institutionally courageous, beautifully installed, impolite, and full frontal and well published. The artists, the museum, director Browne and curator Robin Metcalfe, all deserve kudos and perhaps a few trophies at awards time.

Garth Clark is the Chief Editor of CFile.

Any thoughts about this post? Share yours in the comment box below.

Videos courtesy of the museum.

Thank you so much for the site. Totally enjoyed it. Only wish that I could have seen the exhibition. I have always loved the work of Leopold, Richard, and Paul… And it is about time that that someone fucked over the ‘Love’ painting. Good job Richard.

Dick Hay

Thank you so much for the site. Totally enjoyed it. Only wish that I could have seen the exhibition. I have always loved the work of Leopold, Richard, and Paul… And it is about time that that someone fucked over the ‘Love’ painting. Good job Richard.

Dick Hay